Imagine walking with a curious child through a garden filled with birds. Richard Feynman, the Nobel–winning physicist, recalled such childhood walks with his father. Instead of impressing his son with the scientific names of birds, Feynman’s father pointed out the thrush’s song, the way it cared for its young, and the mystery of how it navigated across continents. “You can know all those names … and still know nothing about the bird,” Feynman later explained. This early lesson underscored a crucial distinction between merely knowing words and understanding underlying phenomena. It shaped Feynman’s career and influenced the learning method that bears his name. Genius, he discovered, is less about innate talent and more about climbing through levels of thought — from rote memory to metacognitive mastery — while constantly simplifying and explaining ideas to others.

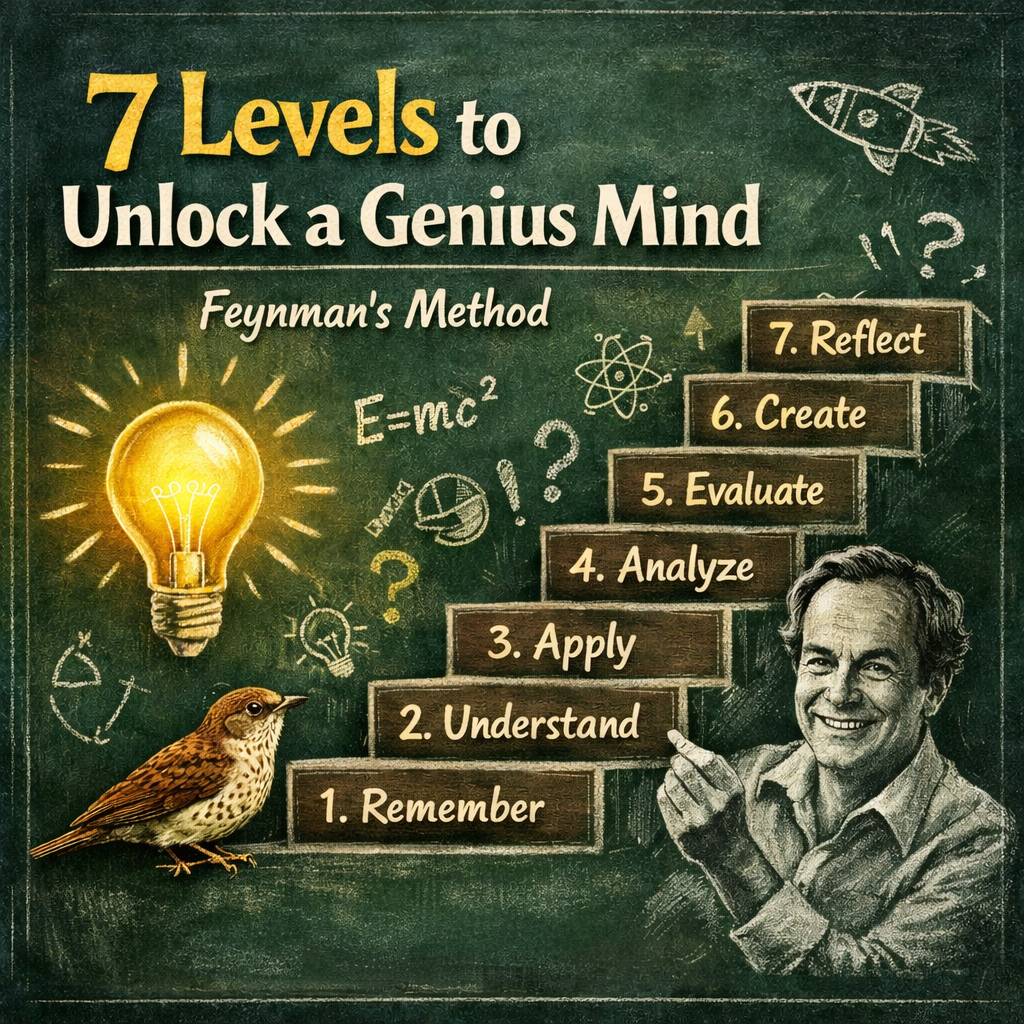

Today many educators recognise a similar staircase in Bloom’s revised taxonomy, which classifies cognitive processes from remembering to creating. Feynman’s four–step technique — map what you know, teach it, identify gaps, and review and refine — provides a practical way to move up these levels. By combining Feynman’s approach with Bloom’s hierarchy and adding a final layer of self‑reflection, we can outline seven levels that unlock deeper learning and creativity.

Overview of the Seven Levels

The journey toward mastery is not linear but hierarchical. Each level builds on the previous one: you must remember before you can understand, and you must evaluate before you can create. The table below summarises the seven levels, the key actions involved, and how Feynman’s technique supports movement through them.

| Level | Key actions | Feynman focus |

| 1. Remembering | Recall, list, identify | Map what you know |

| 2. Understanding | Explain, summarise, paraphrase | Explain to a child |

| 3. Applying | Use, demonstrate, solve | Practise in real situations |

| 4. Analyzing | Compare, differentiate, examine | Take things apart, compare ideas |

| 5. Evaluating | Critique, justify, assess | Test understanding and refine |

| 6. Creating | Design, invent, construct | Generate new ideas from knowledge |

| 7. Reflecting | Observe, question, self‑monitor | Think about how you learn |

Level 1 – Remembering

At the base of the hierarchy lies remembering, the ability to recall facts, terms, and basic concepts. In Bloom’s framework, this involves listing, identifying, or reciting information. Students often mistake this level for learning because it feels like work. Feynman’s childhood story illustrates its limits: learning the names of birds in several languages doesn’t tell you how they fly or why they sing.

Example: Imagine a medical student memorising the names of the cranial nerves. She can recite them flawlessly but cannot explain their functions. Her knowledge is fragile; without repetition, she soon forgets.

Moving forward: Use Feynman’s first step — map what you know. Write down everything you remember about the topic, grouping facts and noting areas of uncertainty. Engage in active recall by testing yourself rather than re‑reading notes. Preparing flashcards or summarising aloud helps strengthen memory and sets the stage for deeper understanding.

Level 2 – Understanding

Once you can remember information, the next step is understanding — grasping meaning, interpreting ideas, and connecting them in your own words. This aligns with Feynman’s admonition that you truly know something only when you can explain it. The second step of his technique is to teach the concept to a 12‑year‑old.

Example: Consider learning Einstein’s mass–energy equation. Instead of merely stating E = mc², you explore why energy and mass are equivalent and why the speed of light squared acts as a conversion factor. By drawing diagrams or using analogies (e.g., mass as “frozen energy”), you can explain the concept to a younger sibling.

Moving forward: Simplify by eliminating jargon. After teaching the concept in plain language, identify gaps — the areas where you stumble or rely on memorised phrases. Return to the source material until you can fill those gaps. Asking “why?” repeatedly helps transform disconnected facts into a coherent understanding.

Level 3 – Applying

Applying knowledge means using what you understand in new situations. It requires more than comprehension; you must execute procedures and test concepts in practice. Feynman believed learning becomes real when you “take things apart, see how they work” .

Example: A budding software developer learns the syntax of a programming language. Application begins when she writes a small programme — perhaps a calculator — applying functions and loops she has studied. Similarly, a biologist moves from understanding enzyme kinetics to designing an experiment that measures reaction rates.

Moving forward: Consciously seek opportunities to practise what you’ve learned. Solve problems, build prototypes, conduct simple experiments, or draft blog posts applying theoretical ideas. This hands‑on engagement not only solidifies understanding but also reveals misconceptions.

Level 4 – Analyzing

Analysis involves breaking ideas into parts, exploring relationships, and comparing alternatives. It marks the transition from learning what others have said to becoming a critical thinker. Feynman’s description of science lessons emphasised examining mechanisms rather than accepting definitions. Instead of memorising that “energy makes it move,” he suggested taking apart a toy dog to observe gears and springs.

Example: In history, analysing the causes of the French Revolution means examining economic pressures, class tensions, and philosophical ideas, then comparing historians’ interpretations. In mathematics, you might dissect a complex proof to understand how each lemma contributes to the theorem.

Moving forward: Create charts or mind maps to connect causes and consequences. Compare competing theories and ask what assumptions underpin them. Feynman’s third step — review and refine — fits here: revisit your explanations, identify weaknesses, and rebuild your understanding with deeper insights.

Level 5 – Evaluating

At the evaluation level, you judge the value of ideas, methods, or arguments using appropriate criteria. This goes beyond analysis by asking not just how parts relate but whether they are valid or useful. Feynman advised testing your understanding by teaching someone else and listening for questions you cannot answer. Evaluation also mirrors his principle that complexity and jargon often hide a lack of understanding.

Example: A policy analyst reading multiple research papers on climate policy doesn’t merely summarise them; she assesses the quality of their data, the robustness of their methods, and the logic of their conclusions. She weighs conflicting recommendations to decide which policies deserve public investment.

Moving forward: Practise critical reading. Ask why a particular method was chosen and whether alternative explanations exist. When debating or writing essays, justify your position with evidence and acknowledge limitations. Testing your conclusions by sharing them with peers and inviting critique helps refine judgment.

Level 6 – Creating

At the top of Bloom’s cognitive hierarchy is creating — generating new ideas, products, or perspectives. This level synthesises all previous ones: you recall facts, understand principles, apply methods, analyse relationships, and evaluate options to produce something novel. It reflects Feynman’s curiosity‑driven research in quantum electrodynamics and his ability to see patterns others missed.

Example: A composer combines knowledge of harmony and rhythm with personal expression to write an original piece. An entrepreneur draws on market research and technical understanding to design a new app. In science, creating might involve proposing a hypothesis that explains an anomaly in existing data.

Moving forward: Encourage free exploration and play. Cross‑pollinate ideas from different domains; many breakthroughs occur at the intersection of fields. When experimenting, treat failures as feedback rather than setbacks. Feynman himself delighted in “the pleasure of finding things out” and often pursued seemingly trivial puzzles that later led to significant insights.

Level 7 – Reflecting

Reflection, or metacognition, adds a final layer to the learning process. It involves thinking about your thinking — examining how you learn, recognising strengths and weaknesses, and adjusting strategies accordingly. Research highlighted by Edutopia notes that when students reflect on how they learn, they achieve at higher levels and become more self‑reliant.

Example: After completing a semester, a student reviews her study habits. She realised that group discussions helped her understand complex theories, whereas cramming the night before exams left her anxious and forgetful. By keeping a learning journal, she monitors which techniques work and which don’t.

Moving forward: Allocate time for regular self‑assessment. Ask yourself what strategies were most effective and where you struggled. Metacognitive questions such as “What confuses me?” or “How did I overcome a challenge?” foster awareness and resilience. Feynman’s habit of rewriting explanations and revisiting concepts embodies this reflective cycle; he was constantly curious about his own understanding.

Takeaways

Unlocking a genius mind is not reserved for prodigies. It is a disciplined journey through progressive levels of cognition, from remembering facts to reflecting on your own thinking. Richard Feynman’s method — mapping knowledge, teaching it simply, identifying gaps, and refining through practice — acts as a guide across these stages. Bloom’s revised taxonomy provides a scaffold that shows why each level matters and how they build upon one another.

By consciously moving from remembrance to understanding, from application to analysis, and from evaluation to creation, and by ending with reflection, we transform learning from an act of consumption into one of active inquiry and innovation. In Feynman’s words, names and definitions alone don’t confer understanding. To think like a genius, we must engage with ideas deeply, question continually and make knowledge our own.

references

- Farnam Street Media. (n.d.). Feynman technique: The ultimate guide to learning anything faster. Farnam Street. Retrieved January 7, 2026, from https://fs.blog/feynman-technique/

- Farnam Street Media. (n.d.). Richard Feynman: The difference between knowing the name of something and knowing something. Farnam Street. Retrieved January 7, 2026, from https://fs.blog/richard-feynman-knowing-something/

- Price-Mitchell, M. (2015, April 7). Metacognition: Nurturing self-awareness in the classroom. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/blog/8-pathways-metacognition-in-classroom-marilyn-price-mitchell

- Ruhl, C. (2025, March 11). Bloom’s taxonomy of learning. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/blooms-taxonomy.html

These references underpin the explanations of the seven levels of learning and Feynman’s method presented in the article.

Discover more from RETHINK! SEEK THE BRIGHT SIDE

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.