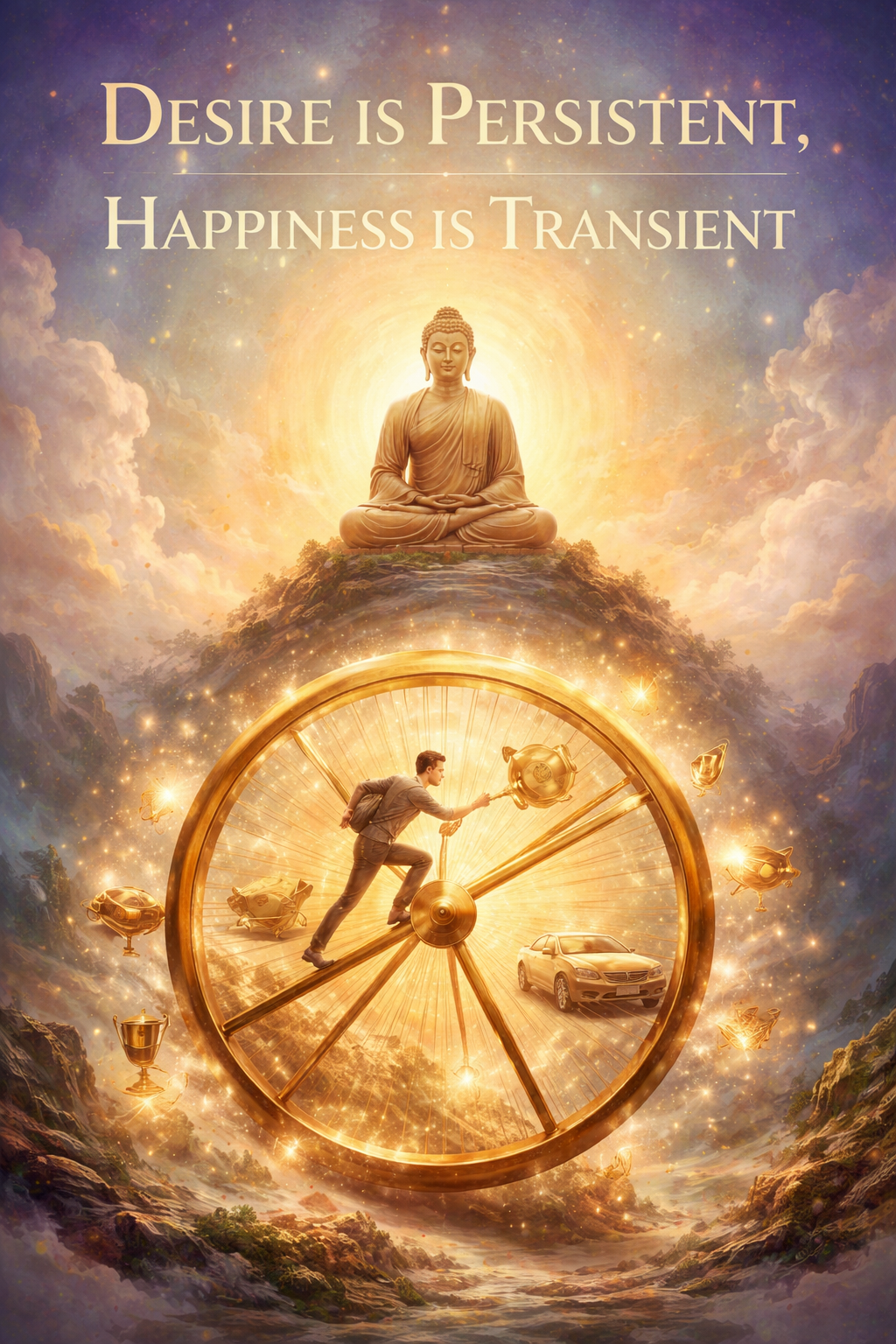

Once upon a time in ancient India, a young prince lived in a palace of plenty. Surrounded by luxury, he had every pleasure at his fingertips, yet contentment eluded him. Curious about life beyond indulgence, he ventured out and witnessed sickness, old age, and death. He realized that no amount of worldly delight could shield him from life’s pain. He decided to leave his palace in search of truth. That prince, Siddhartha Gautama, became known as the Buddha. His insight was simple yet profound: desire is endless, while the happiness it brings is fleeting. This timeless wisdom illustrates that chasing pleasure is like drinking saltwater. It quenches thirst briefly only to make it worse. This resonates across cultures and eras. Modern psychology and neuroscience now confirm the teachings of ancient sages. They show that the more we feed desire, the more it grows. This keeps us on a treadmill of wanting more and more. In this essay, we explore the lasting philosophical teachings about the traps of desire. These teachings are supported by today’s science of the mind and brain.

Ancient Wisdom: The Cycle of Craving and Dissatisfaction

Buddhism – Craving as the Root of Suffering: Over 2,500 years ago, the Buddha taught a profound truth. He explained that life’s unsatisfactoriness, known as dukkha, arises from craving, called taṇhā. According to the Second Noble Truth of Buddhism, craving and attachment to impermanent things inevitably lead to suffering. We grasp at pleasures. We cling to people or outcomes. We only suffer when they change or fade. All things eventually do. In Buddhist philosophy, this endless cycle of desire and disappointment keeps us trapped. It binds us in saṃsāra, a wandering journey of rebirth and dissatisfaction. Fulfillment never fully satiates craving; satisfying one urge provides only temporary relief before a new want arises. The Dhammapada, a collection of the Buddha’s sayings, vividly illustrates this. Just as a felled tree grows again if the roots are unharmed and strong, suffering sprouts repeatedly. This continues until the tendency to crave is rooted out. In other words, unless we uproot craving itself, desires will keep regenerating, and true contentment will remain out of reach.

Epicurus – Natural vs. “Vain” Desires: Across the world in ancient Greece, the philosopher Epicurus also warned against limitless wanting. He drew a sharp distinction between natural and empty (vain) desires. Natural desires can be necessary, like the need for food, shelter, and friendship. They can also be merely natural but not essential, like a preference for a gourmet meal over simple food. These are generally finite and easy to satisfy. By contrast, vain desires – for great wealth, power, or fame – have no natural limit. As Epicurus observed, if one desires wealth or power, it is always possible to get more. The more one acquires, the more one wants. Such desires are not rooted in true bodily needs. They are driven by social comparison and false beliefs. For example, there is a notion that unlimited money will secure everlasting happiness. Epicurus advised that chasing these insatiable cravings only fuels anxiety and misery. His recipe for happiness was moderation and focusing on simple, truly fulfilling pleasures. By appreciating enough, one could attain ataraxia – a tranquil state of contentment, free from the torment of endless wanting. As he famously noted, if you wish to make a man wealthy, do not give him more money. Instead, reduce his desires. In reducing superfluous desires, we remove the pain of constant unsatisfied yearnings.

Stoicism – Mastery Over Desire: Stoic philosophers like Epictetus and Seneca echoed these insights. They argued that true freedom and peace come not from gratifying every desire, but from mastering desire itself. Epictetus was once a slave. He taught that anyone can be internally free. This freedom comes by learning to want only what is within one’s control. He advised, “Freedom is not achieved by satisfying desire.” He urged people to drop obsessive wants that chain them to external things. To the Stoics, desires for externals (wealth, pleasure, even life itself) place our happiness at the mercy of chance. They believed our happiness also depends on circumstance. Seneca, in turn, observed that a person who always craves more is forever poor, no matter how much he owns. Seneca wrote in his letters, “The man who has too little is not poor. The man who craves more is.” By contrast, the person who has learned to be content with what is enough can never truly be impoverished. The Stoics cultivated an inner fortress of equanimity. They desired less and aligned their wants with what life handed them. This approach allowed them to attain a steady tranquility (ataraxia or apatheia). In practical terms, this meant training oneself, through reason and reflection, to resist tempting impulses. It also involved remembering that indulging whims often leads to more unrest. As Epictetus taught, many of our desires are based on faulty thinking – we assume obtaining X (the promotion, the indulgent food, the romantic partner, etc.) will secure lasting happiness, when in reality the satisfaction is often transient. Thus, the Stoics prescribed shifting our mindset rather than chasing more objects of desire. By wanting only what is within our control – our own actions and attitudes – and cultivating gratitude for what we have, we can remain “undisturbed” (the greatest good, in Seneca’s words) regardless of external changes. These ancient philosophies all converge on a key point: fulfilling desire is a Sisyphean task – like trying to fill a bottomless pit – and true well-being lies in taming the wanting itself.

The Hedonic Treadmill: Psychology of Adaptation and Endless Wanting

Centuries later, modern psychology discovered what those sages intuited. Even when our wishes are granted, the boost in happiness is usually temporary. We quickly adapt to new pleasures or improved circumstances – a phenomenon psychologists call hedonic adaptation. Like a person walking on a treadmill, we move forward but ultimately stay in the same place in terms of happiness. This is often illustrated by the story of lottery winners. In the 1970s, researchers famously compared people who had won the lottery with those who had suffered paralyzing accidents. After an initial surge or drop in happiness following these events, within a year or so both groups had drifted back toward their prior baseline levels of happiness (Brickman et al., 1978). In other words, good fortune and even tragedy did not permanently alter their overall life satisfaction. As one early paper put it, people have a nearly fixed “happiness set-point” to which they eventually return. We incessantly seek improvements. We pursue a higher income, a nicer home, or a new relationship. We believe these improvements will make us happier. As soon as we attain them, our expectations rise. Our desires increase as well. They cancel out any happiness gains. If you get a raise at work, for example, you might feel delighted for a while. However, the extra money quickly becomes the new normal. You soon begin to desire even more or eye the next promotion. This “hedonic treadmill” ensures that no achievement or acquisition ever keeps us satisfied for long. We crave, we attain, we adapt. Then, we crave anew. This cycle is very much like the saṃsāra described in Buddhism.

Modern life is rife with examples of this treadmill. Consider the consumer who upgrades to the latest smartphone. For a brief period, they delight in its shiny new features. But soon, the novelty wears off and that phone seems commonplace – until an even newer model comes out and the itch for upgrade starts again. The same pattern occurs with social media “likes”, fashion trends, and even life milestones. Psychologists have noted that we often overestimate how much a new possession or achievement will make us happy and underestimate how quickly we will adapt to it. This error in forecasting leads us to keep pursuing the next “fix” of happiness, often at the expense of contentment in the present. The enduring desire outlasts the temporary happiness, keeping us running in place. In fact, chasing ever-more can create unhappiness. The stress of comparison (“keeping up with the Joneses”) contributes to anxiety. Additionally, the disappointment when reality fails to match our inflated expectations leads to dissatisfaction. As society becomes richer, people’s aspirations inflate. This is a point noted in the so-called Easterlin Paradox. Here, average happiness levels often stagnate even as average incomes rise beyond a certain point. Wanting more, it turns out, is a recipe for feeling you have less. This is why gratitude practices are important. Consciously appreciating what one already has boosts happiness. They counteract our tendency to take things for granted. Additionally, these practices help us resist the urge to constantly seek more.

The Neuroscience of Craving: Dopamine and the Endless Pursuit

What is it about the human brain that makes desire so persistent? Neuroscience offers some answers. At the core is a neurochemical called dopamine, often nicknamed the “reward” neurotransmitter. But dopamine is really less about the reward itself (the enjoyment) and more about anticipation and wanting. When we desire something – whether it’s a slice of cake, a new gadget, or a hit of a drug – the brain’s dopamine circuits light up, creating a motivational push towards the goal. This system, centered in the midbrain’s ventral tegmental area and projecting to the nucleus accumbens and frontal regions, evolved to drive us towards things needed for survival (like food, sex, social bonding). However, it also has the side effect of pushing us to pursue more and more rewards, sometimes heedless of whether those rewards truly improve our well-being.

Crucially, dopamine is the chemistry of craving, not of contentment. Research by neuroscientists Kent Berridge and Terry Robinson distinguishes between “wanting” and “liking.” “Liking” refers to the actual pleasure or satisfaction we experience from something enjoyable (and it engages opioid and other neurotransmitter systems), whereas “wanting” refers to the motivational drive to obtain it . Dopamine is heavily involved in wanting: when dopamine surges, craving intensifies – we feel compelled to seek the reward. But boosting dopamine does not necessarily increase the actual pleasure (liking) when the reward is obtained . In fact, it’s possible to want something more than you like it. This is seen dramatically in addiction: an addict might report that the drug doesn’t even feel that good anymore, and yet they experience an overwhelming craving for it. That is a sign of dopamine-driven “incentive salience” (wanting) decoupled from genuine enjoyment. The more dopamine is released, the more one craves – even if each fulfilling of desire yields diminishing satisfaction . In our everyday pursuits, this can translate into an endless loop: we chase the next shiny reward, get a short-lived buzz, and quickly find ourselves hungry for something new. It’s a neurological correlate of the hedonic treadmill.

Behavioral experiments show how powerful this wanting circuit can be. In classic studies, rats will repeatedly press a lever to stimulate the dopamine pathways in their brains – to the point of ignoring food, water, and rest. They are, in a sense, wired to want, even at the cost of life’s necessities. Humans have analogous experiences: think of binge-watching one more episode even when the enjoyment has dulled, or scrolling a social media feed compulsively without real joy. These habits are powered by the promise of “maybe the next one will be rewarding,” a dopaminergic promise that keeps us hooked. Modern addictions – not just to substances but to behaviors like online shopping, gambling, or smartphone use – exploit this dopamine loop, giving us just enough reward to keep the wanting alive. Each hit of pleasure is transient, but the craving it sparks tends to last and push us to seek again. Neuroscientists also find that repeated bursts of dopamine (through repeated reward-seeking) can sensitize the brain’s wanting systems . This means the craving response becomes stronger over time – we become even more prone to desiring the next hit, while our capacity to enjoy it doesn’t proportionally increase. In short, our brains can trap us in a cycle of pursuing pleasures that don’t fulfill us for long. The ancient Buddhist metaphor of craving as a fire – always needing more fuel – is remarkably apt, now backed by neural evidence. Dopamine sparks the flame of wanting, but feeding that flame with what it wants only makes it burn hotter for more.

Breaking the Cycle: Mindfulness and Cognitive Mastery of Desire

If the default state of human psychology is to get caught in this desire→pleasure→adaptation→renewed desire loop, is there a way out? Ancient wisdom suggested training the mind – through mindfulness, contentment, and reframing one’s perspective – to short-circuit the automatic link between craving and suffering. Modern psychology and neuroscience affirm that we can indeed intervene in the cycle. Practices like cognitive reframing (actively changing how we think about what we want) and mindfulness meditation (observing our thoughts and urges without automatically reacting) have been shown to reduce the grip of craving on us.

Cognitive reframing is a cornerstone of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and involves reinterpreting a situation to change its emotional impact. For example, instead of thinking “I need that promotion or I’ll be a failure,” one might reframe to say, “It would be nice to have the promotion. However, my worth isn’t defined by my job title.” This kind of mental shift engages the brain’s executive control centers. It particularly involves regions of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) that are responsible for reasoning. These also manage self-control and impulse inhibition. Neuroimaging studies show that when people employ reappraisal strategies, the prefrontal cortex ramps up its activity. For instance, a smoker might tell themselves, “That cigarette craving is just a sensation. It will pass.” In this way, the primitive reward regions (like the nucleus accumbens and amygdala) show reduced activity. In one brain imaging experiment, smokers were shown smoking cues. They were asked to either indulge the craving or resist it cognitively. During resistance, researchers observed increased activation in the dorsolateral PFC. This region is for self-control and focus. They also noticed decreased activation in the ventral striatum and ventral tegmental area. These areas are key parts of the dopamine “wanting” circuit. The stronger the PFC activity and the more the reward regions quieted, the more the individuals’ self-reported craving went down. In fact, the PFC and the ventral striatum see-sawed: as top-down control strengthened, the craving signals in the reward hub subsided. This offers a neural picture of willpower in action. It essentially shows the brain learning to override the impulse for immediate gratification. Such cognitive control is like a brake that can slow the hedonic treadmill.

Mindfulness meditation complements this by training awareness and acceptance of the present moment. Rather than immediately pursuing a desire, a mindful approach teaches one to observe the feeling of wanting. It does this without judgment or resistance. Over time, this can weaken the habitual link between “want -> must have -> act”. Mindfulness increases our tolerance of discomfort on a psychological level. This includes the discomfort of an unfulfilled urge. It allows the craving to peak and then pass away naturally. Neuroscientifically, long-term meditators show greater activation in prefrontal regions. They also have increased activation in the anterior cingulate cortex. These areas are involved in attention and emotion regulation. This occurs even when they are exposed to tempting or painful stimuli. Studies on mindfulness-based interventions for addiction find that they help restore balance in the brain’s control circuits. For example, mindfulness practice can strengthen connectivity in the brain’s executive control network. This includes prefrontal areas. Meanwhile, it reduces activity in the default mode network. This network is associated with mind-wandering and self-centered thinking that can fuel cravings. In practical terms, a person practicing mindfulness might notice “Ah, I’m feeling a strong desire to eat a cookie. It’s just a sensation of craving; it will diminish if I don’t feed it.” By not automatically reaching for the cookie, they break the conditioned link between wanting and reward. Over time, the craving arises with less intensity because the brain learns that not every desire will be indulged. This is akin to what Stoics practiced in a different form – delay and examine your impulses rather than immediately satisfying them. Modern therapists often teach clients skills like urge surfing (riding the wave of a craving until it subsides) and gratitude focus (counteracting the urge for more by appreciating what one has) – both of which draw on mindfulness and reframing techniques.

The result of these practices is empowering: desire no longer controls us; we gain a measure of control over desire. Life inevitably involves desires and pleasures. Buddhism, for instance, never said all desire is bad. It only highlighted unwholesome craving that leads to suffering. The goal is not to become a cold ascetic with no enjoyment, but to enjoy without clinging. Mindfulness and cognitive strategies help by instilling a reflective pause between craving and response. They engage our brain’s more rational, future-oriented systems so that we aren’t yanked around by every dopamine squirt of wanting. This aligns perfectly with the old philosophies. The Stoics called for exercising reason over impulse. Epicurus advised mindfully choosing simple pleasures over wildly chasing luxury. The Buddha encouraged being awake and aware rather than a slave to craving. In essence, modern science is confirming that freedom from the pain of endless desire is attainable. We can achieve this by training our mind and brain to approach desire in a new way. We learn to want wisely and in balance, rather than indulge in dopaminergic excess that leaves us emptier.

Conclusion: Toward Lasting Contentment

From the Buddha’s sermons under the Bodhi tree to the latest fMRI studies of the brain, a consistent truth emerges. Happiness that depends on endless desire is inherently fragile. It is also transient. Our desires reset like a clock, always ticking forward, always seeking the next thing. Pleasure flickers and fades. If we keep seeking it in the same way, we remain on the treadmill. We run hard yet arrive nowhere new. Lasting contentment, it seems, comes not from satisfying every yearning, but from understanding yearning’s nature and making peace with it. This doesn’t mean we abandon all goals or pleasures. It means we recognize their fleeting nature. We stop expecting any single achievement or acquisition to finally make us happy forever. The ancient sages knew this. Modern science corroborates it. The key is learning to appreciate life without being ruled by incessant want. We moderate our desires. We cultivate gratitude for what we have. By strengthening our mental balance, we step off the treadmill. This allows us to find moments of true fulfillment in the here and now. In the words of the Stoic Epictetus, we become “wealthy” by learning to want less, not by accumulating more. The Buddha taught us to free ourselves from compulsive craving. By doing so, we uproot the source of much of our sorrow. The persistent flame of desire no longer burns us. Instead, a steady glow of contentment can light our way. Wisdom and mindfulness can transform desire. This transformation allows us to enjoy life’s pleasures without being enslaved by them. In that balanced state, we finally find that elusive tranquility. Ancient philosophers and modern psychologists alike extol this tranquility as the foundation of genuine happiness.

References

Brickman, P., Coates, D., & Janoff-Bulman, R. (1978). Lottery winners and accident victims: Is happiness relative? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36(8), 917–927.

Berridge, K. C., & Robinson, T. E. (2016). Liking, wanting, and the incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. American Psychologist, 71(8), 670–679.

Epicurus. (n.d.). Principal Doctrines (C. Bailey, Trans.) . (Original work ~3rd century BCE)

Kober, H., Kross, E. F., Mischel, W., Hart, C. L., & Ochsner, K. N. (2010). Prefrontal–striatal pathway underlies cognitive regulation of craving. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(33), 14811–14816 .

O’Keefe, T. (n.d.). Epicurus. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from https://iep.utm.edu/epicur/

Rick Hanson. (2022). Dukkha without Tanha: Integrating Buddhist insights and neuropsychology. Insight Journal, 48, 93–110 .

Seneca, L. A. (2017). Letters from a Stoic (R. Campbell, Trans.). Penguin Classics .

Stoic House. (2023, July 10). Does eliminating desire lead towards greater freedom? Monk’s House Blog. (Quote of Epictetus) .

Discover more from RETHINK! SEEK THE BRIGHT SIDE

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.