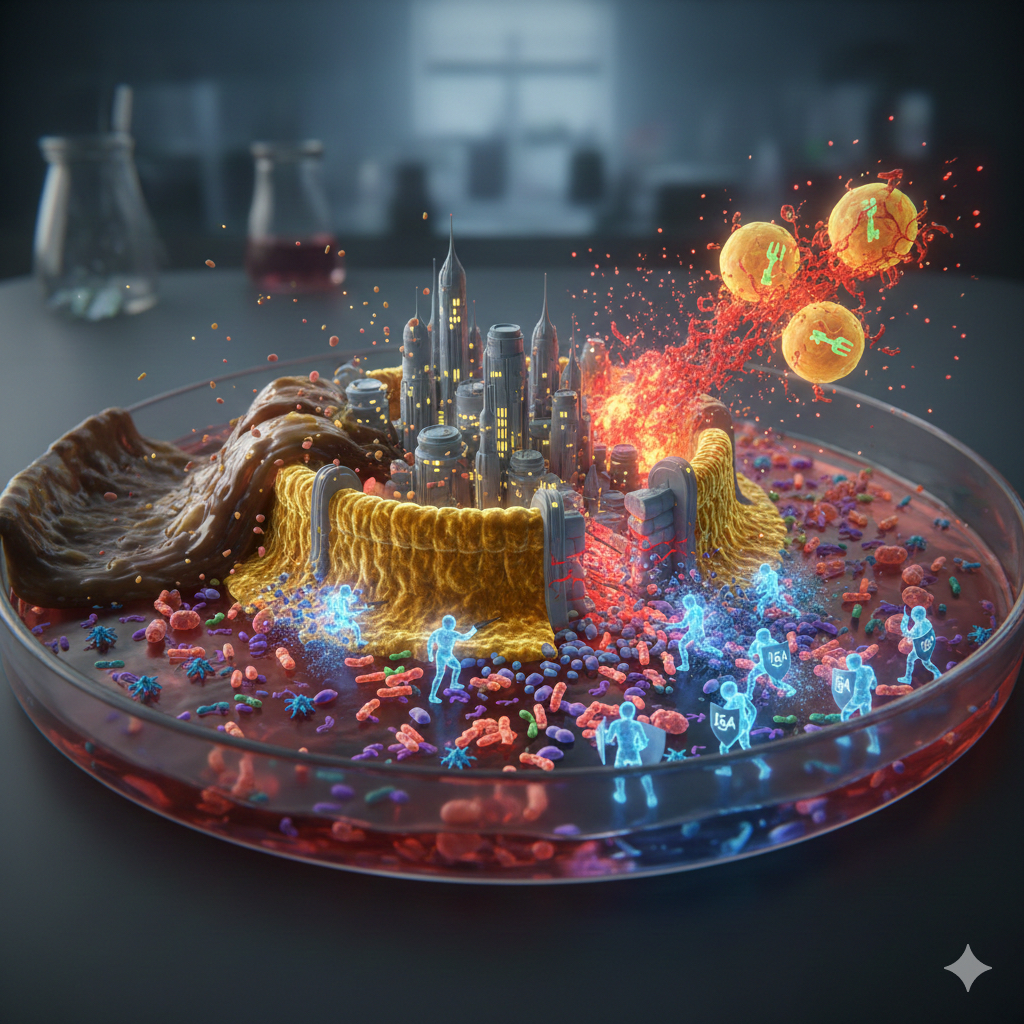

The story of obesity and diabetes is often told through the lens of calories, hormones, and genetics. Yet, the most compelling evidence increasingly points to a tiny, overlooked battlefield hidden within the deepest reaches of the human gut. Imagine the intestine as a sprawling, ancient walled city. Within its walls, millions of bustling citizens (the microbiome) coexist in harmony, managed by a dedicated internal security force—the Peacekeeper Patrol. These peacekeepers are not cells of anger or destruction; they are Immunoglobulin A positive (IgA+) immune cells, and their primary weapon is a coating of molecular velvet: Secretory IgA (SIgA). For years, these peacekeepers have maintained order, keeping the bacterial crowds contained and preventing chaos. But when a high-fat, low-fiber diet sweeps through the city, the Peacekeeper Patrol is disarmed, the walls crumble, and the consequences spread throughout the entire kingdom, resulting in the metabolic siege known as insulin resistance.

This is the central finding of cutting-edge research: the regulation of obesity-related insulin resistance is governed by the state of our gut-associated immune system. To educate the layperson on this profound discovery, we must delve deeper into the specific cells, the molecular pathways, and the compelling evidence that connects a failing gut immune system to chronic disease.

The IgA Factory: A Deeper Dive into Gut-Immunity

The gut is the largest immune organ in the body, hosting a massive network known as the Gut-Associated Lymphoid Tissue (GALT). The IgA+ immune cells originate predominantly in structures called Peyer’s Patches and mature into plasma cells within the lamina propria—the connective tissue layer just beneath the gut lining.

These IgA-producing plasma cells are molecular factories. They secrete dimeric IgA, which is then transported across the epithelial cells to the gut lumen, where it becomes SIgA. The function of SIgA is not to kill bacteria, but to tag, neutralize, and exclude them. Think of it as a sticky molecular coat:

- Containment: SIgA prevents bacteria from directly attaching to the epithelial cells.

- Neutralization: It binds to harmful bacterial toxins and enzymes.

- Shaping the Microbiome: By coating bacteria, SIgA subtly influences which species thrive, ensuring symbiosis (a mutually beneficial relationship) rather than dysbiosis (an imbalance).

The power of this system lies in its non-inflammatory nature. It manages the bacterial population without provoking the full-scale, destructive war typically waged by other immune cells, thus maintaining what is called mucosal tolerance.

Mechanism I: High-Fat Diets Disarm the Peacekeepers

The scientific evidence clearly demonstrates that the modern High-Fat Diet (HFD)—particularly those rich in saturated fat and deficient in fiber—directly cripples this IgA defense system.

Studies on experimental models show that a chronic HFD leads to a significant reduction in the total number of IgA-secreting plasma cells in the lamina propria. Furthermore, the overall fecal IgA concentration plummets. This reduction is not random; it appears to be linked to the loss of microbial metabolites, such as Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) (like butyrate), which are essential for nurturing and activating IgA+ B cells.

The immediate consequence of this IgA deficiency is an epidemic of microbial encroachment. Uncoated bacteria, particularly potentially pathogenic Gram-negative species, begin to migrate closer to the epithelial lining. This proximity causes the disintegration of the gut’s most critical defense: the tight junctions.

The tight junctions are complexes of proteins (occludin, claudins, and zonulin) that act like the mortar between bricks, sealing the epithelial barrier. When IgA is deficient and bacteria are too close, the release of certain bacterial factors triggers the disassembly of these tight junction proteins, leading to increased intestinal permeability, or the infamous “leaky gut.”

The clinical evidence confirms this: IgA-deficient mice fed an HFD rapidly develop severe insulin resistance, whereas their IgA-sufficient counterparts, even when overweight, fare better. This highlights the indispensable role of the IgA shield.

Mechanism II: The Path to Insulin Resistance (Metabolic Endotoxemia)

Once the gut barrier is compromised, a potent toxin escapes: Lipopolysaccharide (LPS). LPS, also known as endotoxin, is a major component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria.

- Metabolic Endotoxemia: LPS leaks from the compromised gut barrier and enters the bloodstream, primarily carried via the portal vein to the liver and then to the rest of the body. Even tiny, seemingly insignificant concentrations of circulating LPS—a condition termed Metabolic Endotoxemia—are sufficient to trigger systemic disease.

- The Inflammatory Cascade: Upon reaching peripheral tissues, especially the metabolically active visceral adipose tissue (belly fat), LPS binds to a specific receptor on the surface of local immune cells (macrophages and others) called Toll-like Receptor 4 (TLR4).

- The NF-\kappaB Switch: The binding of LPS to TLR4 is akin to flipping a major distress switch. It activates a critical signaling pathway known as NF-\kappaB (Nuclear Factor kappa B). NF-\kappaB is a master regulator of inflammation; its activation drives the copious production and release of pro-inflammatory signaling molecules called cytokines (notably Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (TNF-\alpha) and Interleukin-6 (IL-6)).

- The Insulin Blockade: These inflammatory cytokines—TNF-\alpha being the prime suspect—are the direct molecular agents of insulin resistance. In fat cells and muscle cells, TNF-\alpha and IL-6 interfere with the delicate insulin signaling pathway. Specifically, they promote the serine phosphorylation of the Insulin Receptor Substrate 1 (IRS-1) protein, rather than the healthy tyrosine phosphorylation required for insulin function. This effectively muffles the insulin signal, preventing the cell from taking up glucose.

The resulting effect is clear: a tiny breach in the IgA-regulated gut barrier leads to systemic inflammation driven by LPS, culminating in the molecular blockade of the insulin receptor.

The Therapeutic Promise

The discovery that IgA+ immune cells are not merely gut defenders but critical metabolic regulators offers revolutionary therapeutic potential. The focus shifts from solely managing blood sugar to repairing the gut’s immune defenses.

- Targeting IgA Production: Future interventions may include designer probiotics or prebiotics (fibers) formulated specifically to boost the SCFA production necessary for activating and maintaining IgA+ plasma cells.

- Restoring the Defense: The most compelling evidence comes from studies involving adoptive transfer, where healthy IgA+ B cells transferred to sick mice reversed insulin resistance. This concept, while complex for human use, proves that restoring the IgA population is a viable treatment strategy.

- Dietary Repair: Understanding this mechanism underscores the power of a whole-food, high-fiber diet to literally feed and strengthen the IgA peacekeepers, acting as a natural vaccine against chronic metabolic disease.

In conclusion, the battle against obesity and insulin resistance begins not in the blood, but behind the walls of the intestinal city. By understanding the intricate peacekeeper protocol managed by IgA+ immune cells and the catastrophic effects of the high-fat diet on this system, we unlock a powerful new paradigm: metabolic health is inextricably linked to the integrity of the gut’s immune defense.

This comprehensive essay relies on a core body of research that established the link between IgA, gut permeability, inflammation, and insulin resistance.

references

Key References

- Primary Study on IgA and Insulin Resistance

This study serves as the foundational evidence directly linking gut IgA+ cells to metabolic regulation, as discussed in the essay.

Luck, H., Khan, S., Kim, J. H., Copeland, J. K., Revelo, X. S., Tsai, S., Chakraborty, M., Cheng, K., Chan, Y. T., Nøhr, M. K., Clemente-Casares, X., Gaisano, H., Winer, S., & Winer, D. A. (2019). Gut-associated IgA$^{+}$ immune cells regulate obesity-related insulin resistance. Nature Communications, 10(1), 3656. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11370-y

- Link between High-Fat Diet, LPS, and Metabolic Endotoxemia

This seminal work introduced the concept of “metabolic endotoxemia” and the critical role of Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance, which directly relates to the breakdown of the IgA barrier.

Cani, P. D., Amar, J., Iglesias, M. A., Poggi, M., Knauf, C., Bastelica, D., Neyrinck, A. M., Flandez, F. G., Kram-Horon, K. M., Fiedler, M., Williams, K. I., Harreman, M., Woodman, O. L., Muccioli, G. G., Huault, T. L., Pacher, P., Casteilla, L., Pénicaud, L., Alessi, M. C., … Giardina, M. J. (2007). Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes, 56(7), 1761–1772. https://doi.org/10.2337/db06-1491

- TLR4 and Inflammatory Cytokine Pathway (Mechanism of Insulin Blockade)

This research elucidates the molecular mechanism (TLR4 activation leading to inflammation and insulin resistance) that occurs after the LPS leaks through the IgA-compromised barrier.

Shi, H., Kokoeva, M. V., Inouye, K., Tzameli, I., Yin, B. W., & Flier, J. S. (2006). TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid–induced insulin resistance. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 116(11), 3015–3025. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI28898

- Evidence on HFD, IgA Depletion, and Gut Permeability

This supports the section of the essay detailing the HFD’s effect on reducing IgA-producing cells and compromising the epithelial barrier integrity.

Quaglino, F., Vairano, M., Nardelli, S., & Colitti, M. (2021). High-Fat Diet and Age-Dependent Effects of IgA-Bearing Cell Populations in the Small Intestinal Lamina Propria in Mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(3), 1165. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22031165

Discover more from RETHINK! SEEK THE BRIGHT SIDE

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.