Rare genetic diseases often share the same painful bottleneck: each one requires its own custom gene-editing solution. That means unique molecular tools, unique delivery systems, unique safety testing, and unique regulatory hurdles. It’s slow, expensive, and—cruel irony—rare diseases rarely attract enough funding.

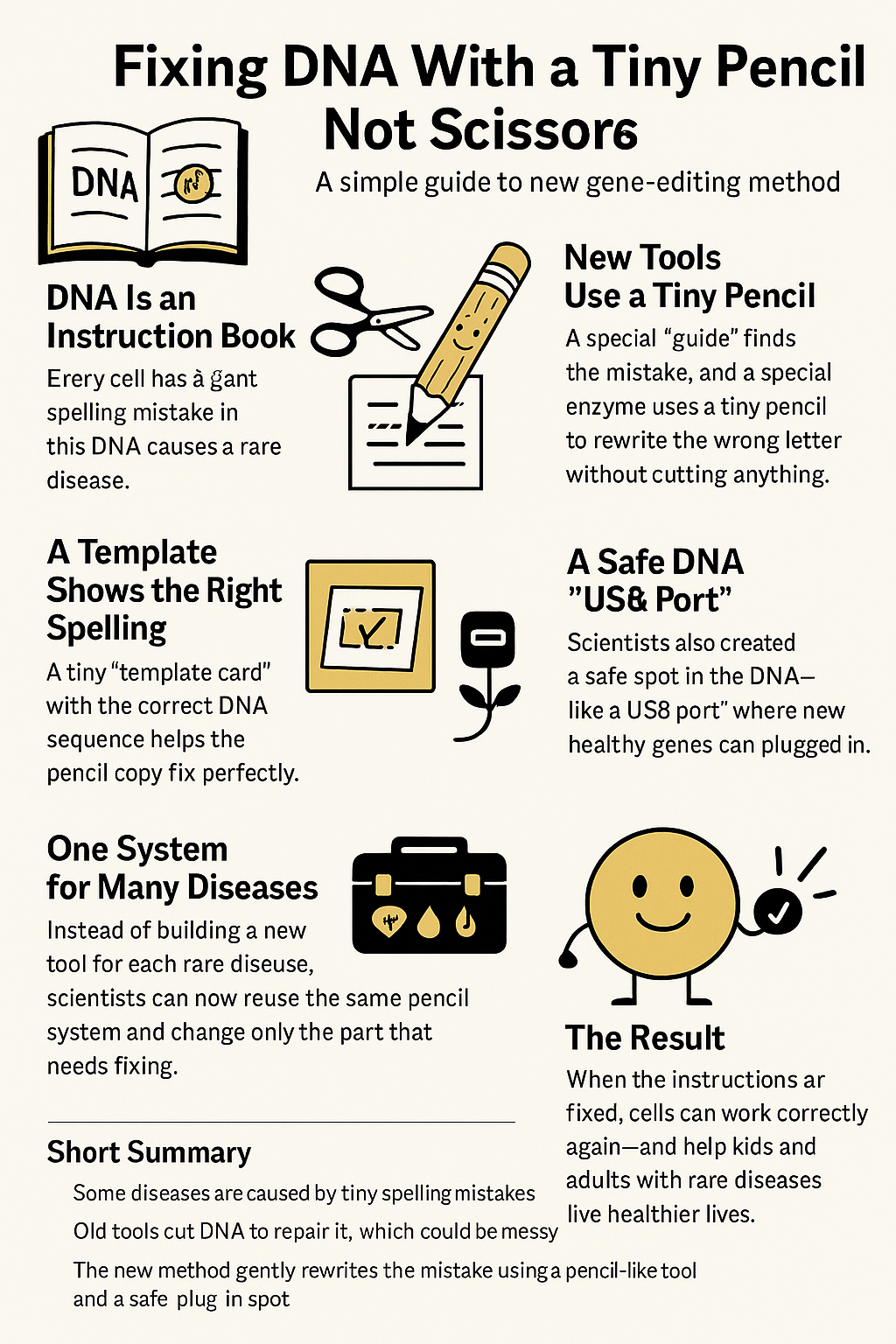

The new approach proposes something radically more elegant: a modular, almost plug-and-play system that could fix many disorders using the same underlying machinery, with only small adjustments for each disease.

Think of it as shifting from hand-carving every gear in a clock to building clocks from a universal parts bin.

————————

The Core Idea: Programmable Gene Writers, Not Cutters

Traditional CRISPR works like biological scissors. Snip the DNA, hope the cell repairs it correctly, and if all goes well, the mutation is fixed. But cutting DNA is messy and risky. Dangerous byproducts—like chromosomal rearrangements—can appear.

This new method relies on gene-writing enzymes that don’t cut DNA at all.

At the heart of the strategy is a programmable DNA-integrating enzyme—in most cases, a synthetic version of a reverse transcriptase (an enzyme that writes DNA using an RNA template). Instead of breaking the genome, it gently inserts corrected genetic information into a precise spot.

Methodologically, it’s closest to:

• Prime editing 2.0

• Optimized transposon-based insertion systems, or

• RNA-guided DNA polymerase systems

Depending on the exact configuration used by the authors.

The new system improves on these precursors by being more efficient and scalable.

————————

How the Strategy Actually Works

Here’s the biological choreography in simple steps:

1.A Guide RNA Finds the Faulty Gene

A short RNA molecule homes in on the DNA sequence where the mutation sits.

This is similar to classic CRISPR, but instead of calling in scissors, it calls in a writer.

2. A DNA-Writer Enzyme Arrives

The enzyme—a modified reverse transcriptase or transposase—attaches to the target region.

But it does not cut.

Instead, it parks gently next to the mutated sequence.

3. A Repair Template is Delivered

This template is a piece of RNA or DNA carrying the correct genetic information—like handing a scribe a clean copy of a damaged sentence.

4.The Enzyme Copies the Correct Sequence Into the Genome

Using the template as instructions, the enzyme rewrites the faulty section of DNA letter by letter.

There’s no double-strand break, no chaos, and minimal risk of unintended mutations.

This is precision editing as a kind of biological calligraphy.

————————

The Key Innovation: A “Universal Landing Pad”

One of the cleverest components is the idea of a shared insertion site engineered into the genome—something the researchers call a multipurpose genomic safe harbor.

Imagine giving every patient cell a little USB port in a safe place in the genome. Into that port, you can plug whatever therapeutic gene is needed for their particular disease.

This avoids the dangerous randomness of older viral gene therapies, which could insert DNA in harmful places.

With a universal landing pad:

• All therapies use the same genomic address.

• Only the cargo (the therapeutic gene) changes.

• Regulatory and safety frameworks can be standardized.

• Costs and development timelines drop dramatically.

It turns genetic engineering from custom tailoring into modular engineering.

————————

Why This Matters for Rare Diseases

Here’s the real breakthrough: one manufacturing process could support dozens or even hundreds of different treatments.

For every new condition:

• You change only the therapeutic payload,

• Keep the same enzyme, the same guide RNAs (with minor tweaks),

• And reuse the same delivery system and integration site.

It’s as if the field found a repeatable recipe, instead of inventing a new cuisine from scratch each time.

This could dramatically accelerate cures for:

• metabolic disorders

• enzyme-deficiency diseases

• blood disorders

• single-gene neurological conditions

• many ultra-rare “orphan” diseases with only a few dozen known patients

For families waiting decades, this approach is more than a methodological advance—it’s a restructuring of hope.

————————

What Still Needs Work

Every scientific leap comes with caution labels.

Efficiency

Early experiments work well in lab settings, but need higher accuracy across many tissue types.

Delivery

Getting the editing system into human cells (especially in the body) remains a long-standing challenge.

Off-target effects

Even without cutting, the enzymes can still slip up. Testing must be deep and exhaustive.

Immune reactions

All gene therapies face the problem of the body’s immune system recognizing the “new” protein as foreign.

————————

The Big Picture

This new platform represents a shift from editing disease by disease to editing via reusable architectures. It’s the same revolution that computers underwent when standardized chips replaced custom wiring.

Instead of the old model—fix one gene at a time—the field is moving toward:

• universal genomic safe harbors

• programmable copying enzymes

• modular payloads

• scalable editing frameworks

If the system matures, it could turn genetic medicine from artisanal craftsmanship into industrial precision—without losing the biological subtlety needed to repair life’s code.

Discover more from RETHINK! SEEK THE BRIGHT SIDE

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.