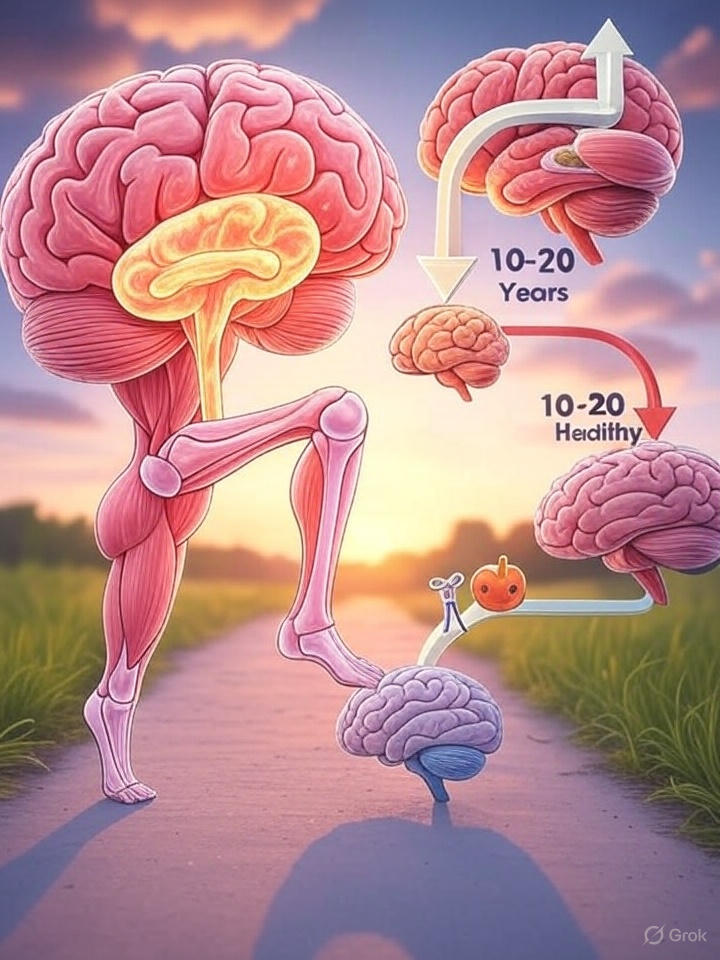

In an era where we’re living longer than ever before, the health of our brains has become a pressing concern for millions. Imagine this: your mind, the epicenter of memories, thoughts, and decisions, begins to show subtle signs of wear and tear long before any serious symptoms appear. But here’s the good news—there’s a golden window of opportunity, spanning 10 to 20 years, where we can potentially alter the trajectory of cognitive decline. This isn’t science fiction; it’s grounded in emerging research on neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. For the average person, understanding this period could mean the difference between a vibrant old age and one marred by forgetfulness and dependency.

Neurodegenerative diseases don’t strike overnight. They brew silently in the background, often for decades, as brain cells gradually deteriorate. Scientists now know that changes in the brain—such as the buildup of toxic proteins like amyloid plaques or tau tangles—can start as early as our 40s or 50s, even if full-blown symptoms don’t emerge until our 70s or later. This “preclinical” phase is where the magic happens. It’s a time when the brain is still resilient, and interventions could halt or slow the damage. Think of it like spotting a small leak in your roof before a storm hits; fix it early, and you avoid a flooded house.

Why does this window exist? Our brains have a remarkable ability called neuroplasticity—the capacity to form new connections and adapt. During these early years of subtle decline, lifestyle choices, medical treatments, and even simple habits can bolster this plasticity. For instance, regular exercise has been shown to increase blood flow to the brain, promoting the growth of new neurons in areas like the hippocampus, which is crucial for memory. Diet plays a role too; anti-inflammatory foods rich in omega-3s, antioxidants, and vitamins can combat the oxidative stress that accelerates aging. And don’t overlook sleep—chronic sleep deprivation can mimic the effects of aging on the brain, impairing clearance of harmful waste products that build up during the day.

But what if we could detect this decline early? Advances in biomarkers are making that possible. Blood tests for proteins like p-tau or neurofilament light chain are being developed to flag risks years in advance. Imaging techniques, such as PET scans, can reveal amyloid deposits before memory lapses begin. For the general public, this means shifting from reactive to proactive healthcare. Annual cognitive check-ups, much like routine blood pressure screenings, could become standard. The goal isn’t just to live longer but to maintain sharp thinking, independence, and joy in later years.

This opportunity isn’t isolated to the brain alone. Recent studies highlight how other parts of the body influence brain health in surprising ways. Take chronic pain, for example. A groundbreaking report from researchers examining osteoarthritis (OA) in the knees has shed light on an unexpected connection. Osteoarthritis, a common joint condition where cartilage wears down, often leads to persistent pain that affects mobility. But it’s not just the knees that suffer—the brain does too.

In this study, participants with chronic knee pain underwent MRI scans to assess brain structure and function, alongside tests for memory and cognition. The results were eye-opening: pain from OA was linked to changes in key brain regions, including the hippocampus (vital for forming new memories), the thalamus (a relay station for sensory signals), and other areas involved in processing pain and emotion. Over time, these individuals showed an increased risk of developing dementia during follow-up periods. Why? Chronic pain isn’t just a local issue; it triggers widespread inflammation and stress responses that ripple through the body, including the brain.

Imagine living with nagging knee pain day after day. It disrupts sleep, limits exercise, and elevates stress hormones like cortisol, which can shrink the hippocampus over time. This creates a vicious cycle: less movement leads to weaker muscles, more weight gain, and further joint strain, all while the brain bears the brunt. The study underscores a holistic view of health—treating joint pain isn’t just about comfort; it’s about safeguarding your mind. For those with OA, options like physical therapy, weight management, or anti-inflammatory medications could double as brain protectors. Even non-invasive approaches, such as mindfulness meditation or acupuncture, have shown promise in reducing pain’s impact on the brain.

This body-brain connection extends beyond pain. Other health factors, like high blood pressure, diabetes, or even hearing loss, can accelerate brain aging by damaging blood vessels or reducing sensory input. The message is clear: what happens in one part of the body doesn’t stay there. Maintaining overall physical health is a frontline defense against cognitive decline.

Shifting focus from the brain, let’s talk about muscles—the body’s workhorses and perhaps the most researched organ when it comes to aging. Unlike the brain, which is tricky to biopsy in living people, muscle tissue is accessible. Researchers can take small samples from healthy individuals across all ages, from toddlers to centenarians, providing a clear picture of how aging unfolds at the cellular level.

Muscle aging, or sarcopenia, is the gradual loss of muscle mass, strength, and function that starts around age 30 and accelerates after 50. By our 80s, we might lose up to 50% of our muscle mass if we’re sedentary. This isn’t just about looking frail; it affects everything from balance to metabolism. Studies show that aging muscles accumulate damaged proteins, mitochondrial dysfunction (the powerhouses of cells fizzle out), and inflammation—mirroring processes in the brain.

Why study muscles so extensively? For one, they’re a window into systemic aging. Hormones like growth factors and myokines released by muscles influence other organs, including the brain. Exercise-induced myokines, for example, can cross the blood-brain barrier and promote neurogenesis. This explains why strength training isn’t just for bodybuilders; it’s a brain booster. A landmark study followed older adults who incorporated resistance exercises twice a week; not only did their muscles grow stronger, but their cognitive scores improved, with better memory and executive function.

Muscle research also highlights interventions that could apply to the brain. Stem cell therapies, for instance, are being tested to rejuvenate aging muscles by replacing worn-out cells. Nutritional strategies, like adequate protein intake (aim for 1.2-1.6 grams per kg of body weight daily), combined with vitamin D and leucine-rich foods, can slow sarcopenia. And let’s not forget the role of hormones—testosterone and estrogen decline with age, contributing to muscle loss, but hormone replacement, under medical supervision, shows benefits.

Parallels between muscle and brain aging are striking. Both involve chronic low-grade inflammation (“inflammaging”), oxidative stress, and cellular senescence—where cells stop dividing but linger, spewing harmful signals. In muscles, this leads to weakness; in the brain, to cognitive fog. Addressing these shared mechanisms could yield broad anti-aging effects. For example, drugs like metformin, originally for diabetes, are being trialed for their potential to extend healthy lifespan by targeting these pathways.

For the general public, the takeaway is empowerment through action. Start with the basics: move more. Aim for 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity weekly, plus strength training. Eat a rainbow of fruits and veggies, lean proteins, and healthy fats. Prioritize sleep—7-9 hours nightly—and manage stress through hobbies or social connections. If you have chronic conditions like joint pain, seek early treatment; don’t let it simmer.

Of course, genetics play a role—some people carry variants like APOE4 that heighten Alzheimer’s risk. But even then, lifestyle modulates outcomes. Twin studies show that identical genetics don’t dictate identical fates; environment matters hugely.

Looking ahead, the 10-20 year window offers hope for personalized medicine. Wearables tracking sleep, activity, and even brain waves could alert us to early changes. Gene editing technologies like CRISPR might one day correct aging-related mutations. In the meantime, community programs promoting “brain-healthy” living—think senior fitness classes or nutrition workshops—can make a difference.

In conclusion, the slow march of brain aging isn’t inevitable doom. With a decade or two of lead time, we have the power to rewrite our stories. By nurturing our bodies, from knees to muscles to minds, we can embrace aging not as decline but as a phase of continued vitality. It’s time to seize that window—your future self will thank you