A man in his late fifties—let’s call him “Rafi”—walked into his doctor’s office clutching a printout of his latest blood test. His LDL cholesterol was high. Not catastrophically high, but high enough to trigger the familiar conversation: statins, dietary fat restrictions, exercise recommendations. Rafi nodded politely, but inside he was terrified. His father had died of a heart attack at sixty-two. Cholesterol felt like a death sentence encoded in numbers.

Rafi did everything he was told, and yet something strange happened: despite lowering his LDL, his triglycerides stayed high, his waistline did not shrink, and the inflammatory markers on his blood tests crept upward. Six months later, a coronary CT scan revealed early plaque build-up.

He stared at the report in disbelief. “But… my LDL is normal now.”

His cardiologist leaned back, slid a scientific paper across the desk, and said gently, “We’ve learned something important in the last decade: not all LDL is the same, and LDL alone isn’t the whole story. Inflammation—and the metabolic chaos that causes it—matters more than we thought.”

This moment is being repeated in clinics around the world. People with “normal” LDL cholesterol still get heart disease. People with high LDL sometimes remain perfectly healthy. What divides them isn’t just LDL—it’s the inflammatory landscape in which those LDL particles travel.

The Old Cholesterol Story

For fifty years, public health messaging simplified heart disease to a cartoonish morality play. LDL was the “bad” cholesterol, HDL the “good” cholesterol, and total cholesterol a rough scoreboard of future danger.

That story was built on partial truth. LDL does participate in plaque formation. HDL does help clear it. But the details were flattened into slogans. In real biology, LDL is not a singular thing—it’s a family of particles with different sizes, densities, and behaviors. Some forms are relatively benign; others are more likely to sneak into arterial walls and spark trouble.

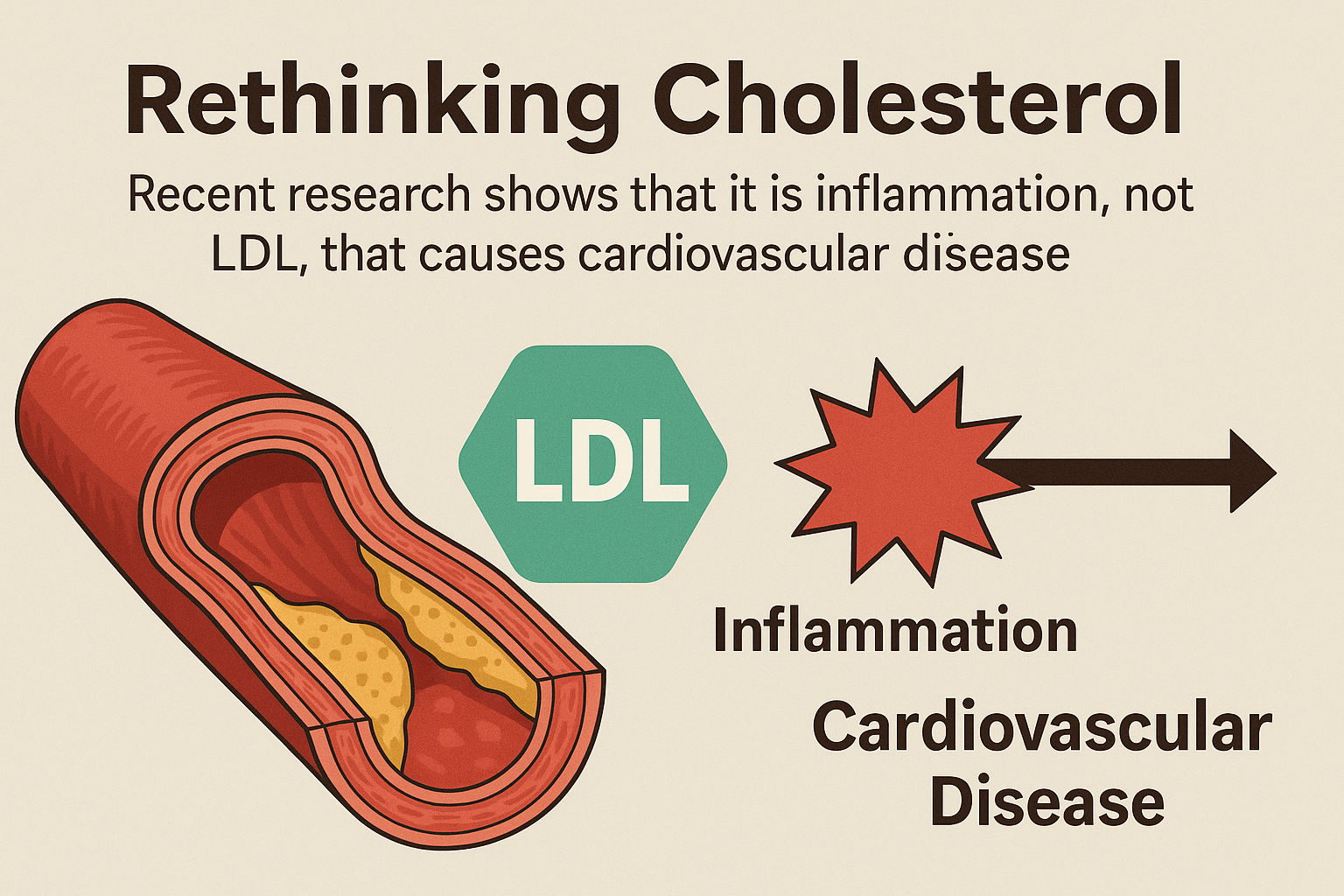

The New Understanding: It’s Not Just LDL, It’s the

Context

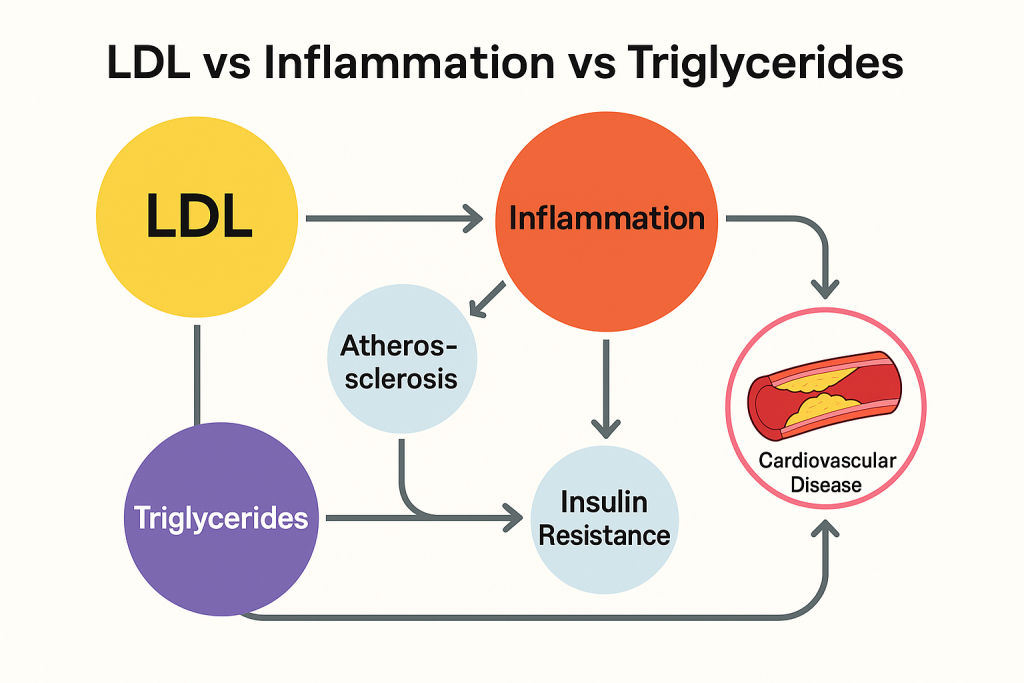

Recent research has overturned the oversimplified model. Scientists now emphasize atherogenic dyslipidemia, a pattern defined by:

• High triglycerides

• Low HDL

• Increased small, dense LDL particles

• Insulin resistance

• Systemic inflammation

In this pattern, LDL becomes dangerous not simply because it exists, but because the internal environment is inflamed and metabolically unstable.

When triglycerides are high—often due to excess refined carbohydrates, sugar, visceral fat, and insulin resistance—the liver overproduces VLDL (very low-density lipoprotein). These triglyceride-rich particles interact with LDL and HDL, transforming them into smaller, denser, more inflammatory forms. These altered LDL particles are the true culprits: tiny enough to slip into arterial walls, sticky enough to stay there, and fragile enough to oxidize.

The inflammation does not merely accompany plaque formation—it primes the immune system to treat these altered particles as foreign invaders. Arteries respond with swelling, immune cell recruitment, and scar-like buildup. Atherosclerosis is, at its core, a chronic inflammatory process.

LDL is the passenger.

Inflammation is the storm.

Key Evidence Changing the Narrative

1.

People with normal LDL can still develop heart disease

Large cohort studies, including the Women’s Health Study and the MESA trial, show that up to 50 percent of heart attacks occur in people with normal LDL levels. Their common features are insulin resistance, high triglycerides, and high inflammatory markers (CRP).

2.

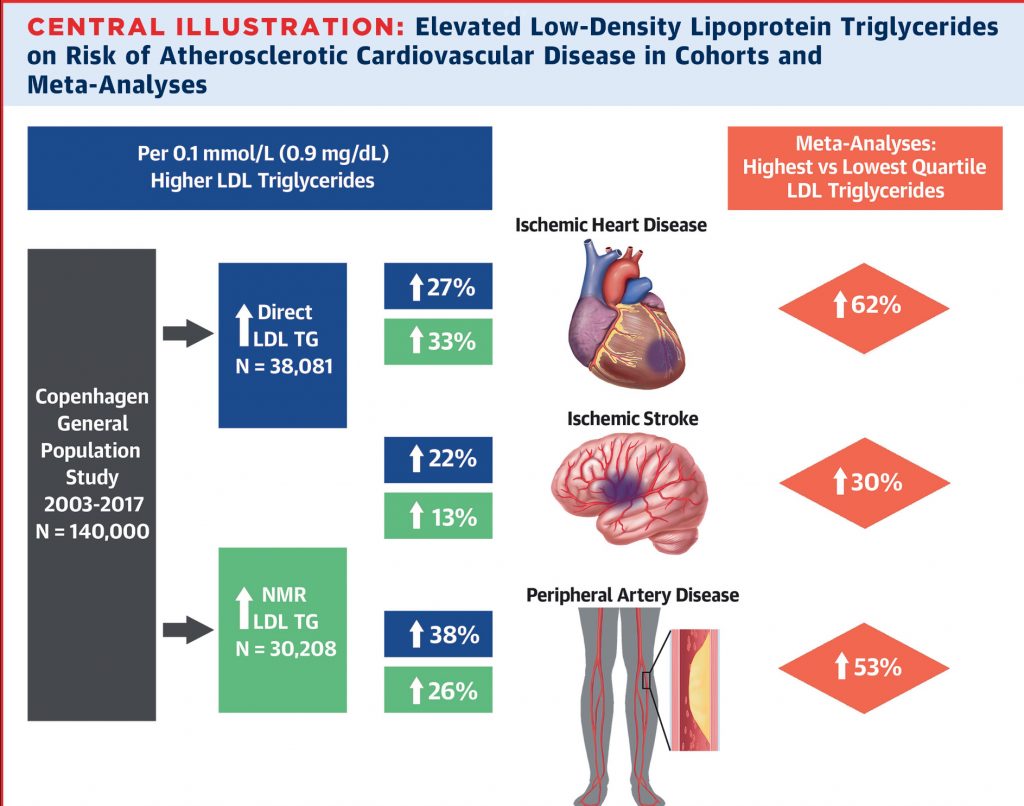

Triglyceride-to-HDL ratio is a powerful predictor

Research consistently shows that the TG/HDL ratio is a superior predictor of cardiovascular risk compared to LDL alone. A high ratio correlates with insulin resistance and small, dense LDL particles.

3.

Inflammation markers predict events even when LDL does not

The CANTOS trial demonstrated that lowering inflammation (independent of LDL) reduces cardiovascular events. Lowering LDL without addressing inflammation leaves residual risk.

4.

LDL particle number and density matter more than raw LDL-C

NMR lipoprotein studies reveal that a person with the same LDL-C number can have vastly different particle counts. More particles mean more “delivery trucks” knocking against arterial walls, raising the probability of infiltration.

5.

Metabolic syndrome is emerging as the real center of gravity

The combination of obesity, high triglycerides, high fasting glucose, low HDL, and hypertension drastically alters lipid behavior. LDL simply travels through this metabolic storm—damaged, oxidized, inflammatory.

What This Means for Everyday People

When people hear “cholesterol,” they picture fatty deposits clogging pipes. Reality is closer to a slow-burning fire in the arterial wall, where inflammation acts as the heat and LDL provides the fuel. Remove the heat, and the fuel behaves differently.

This reframes the goal of cardiovascular prevention:

Instead of focusing only on LDL, we focus on the entire metabolic ecosystem—triglycerides, inflammation, insulin sensitivity, and lifestyle patterns that shape lipid behavior.

The Real Villains: Triglycerides, Inflammation, and Metabolic Dysfunction

High triglycerides are not just a number—they are a biochemical signal that metabolism is overloaded. Excess calories, especially from refined carbohydrates, prompt the liver to convert sugar into fat. The bloodstream becomes flooded with triglyceride-rich particles.

This triggers a cascade:

- LDL becomes small and dense.

- HDL becomes dysfunctional.

- Triglycerides accumulate in the liver and pancreas.

- Fat cells release inflammatory molecules (cytokines).

- Arteries become inflamed, sticky, reactive.

⠀

In this biochemical traffic jam, LDL becomes oxidized or glycated (sugar-damaged), prompting immune cells to attack it. The resulting plaque is not passive fat—it is an inflamed, immune-active lesion trying to heal a wound.

What About Saturated Fat and Diet?

Research has shifted here too. Saturated fat does raise LDL, but not uniformly. Some of the rise is in large, buoyant LDL—less dangerous. Moreover, in people without insulin resistance, the effect is modest. In people with insulin resistance, saturated fat can worsen triglyceride metabolism and inflammation.

The dietary danger signal is not fat alone—it is fat combined with sugar, ultra-processed foods, excess calories, and a sedentary lifestyle. That combination supercharges triglycerides and metabolic inflammation.

Practical Takeaways for Heart Health

Cardiovascular protection comes from calming the inflammation and restoring metabolic stability. Measures supported by strong evidence include:

• Lowering triglycerides through reduced sugar and refined carbohydrates

• Improving insulin sensitivity with regular exercise and weight reduction

• Increasing fiber intake (soluble fiber improves LDL particle clearance)

• Consuming omega-3 fats (which lower triglycerides and inflammation)

• Ensuring adequate sleep (poor sleep worsens inflammation and metabolic markers)

• Avoiding smoking (a major driver of LDL oxidation)

• Managing chronic stress (elevates cortisol, glucose, and inflammatory signaling)

Medications such as statins still have a role; they reduce LDL particle numbers and have anti-inflammatory effects beyond cholesterol. But the modern view treats them as part of a broader strategy—not the whole story.

The New Narrative

LDL cholesterol is neither hero nor villain—it is more like a courier doing its job. Under stable conditions, it delivers cholesterol to cells for repair and hormone synthesis and returns unused cholesterol to the liver. Under inflammatory conditions, it becomes chemically altered and trapped where the immune system overreacts.

Cardiovascular disease emerges not from a single molecule but from a destabilized system.

If Rafi’s story teaches us anything, it’s that numbers alone don’t protect us. What protects us is understanding the orchestra in which LDL plays only one instrument. Triglycerides, inflammation, insulin resistance, oxidative stress, lifestyle patterns—they compose the real score.

When we shift the spotlight from LDL alone to the whole inflammatory symphony, prevention becomes clearer, more accurate, and far more empowering.

Human hearts don’t fail because of a single villain molecule. They falter when quiet fires smolder along arterial walls for years. Put out the fire, and the molecules calm down.

————————

References

Bhatt, D. L., et al. (2019). Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. New England Journal of Medicine, 380(1), 11–22.

Cannon, C. P., et al. (2015). Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. New England Journal of Medicine, 372, 2387–2397.

CANTOS Trial Investigators. (2017). Anti-inflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 377, 1119–1131.

Grundy, S. M., et al. (2018). AHA/ACC guideline on management of blood cholesterol. Circulation, 139(25), e1082–e1143.

Landsberg, L., et al. (2013). Obesity-related hypertension: pathogenesis, cardiovascular risk, and treatment. Journal of Clinical Hypertension, 15(3), 154–165.

Mora, S., et al. (2016). LDL particle cholesterol content and cardiovascular events. JACC, 67(10), 1109–1117.

Ridker, P. M., et al. (2002). Inflammation, CRP, and risk of future cardiovascular events. New England Journal of Medicine, 347(20), 1557–1565.

Sampson, M., et al. (2020). Small dense LDL and cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis, 305, 122–128.