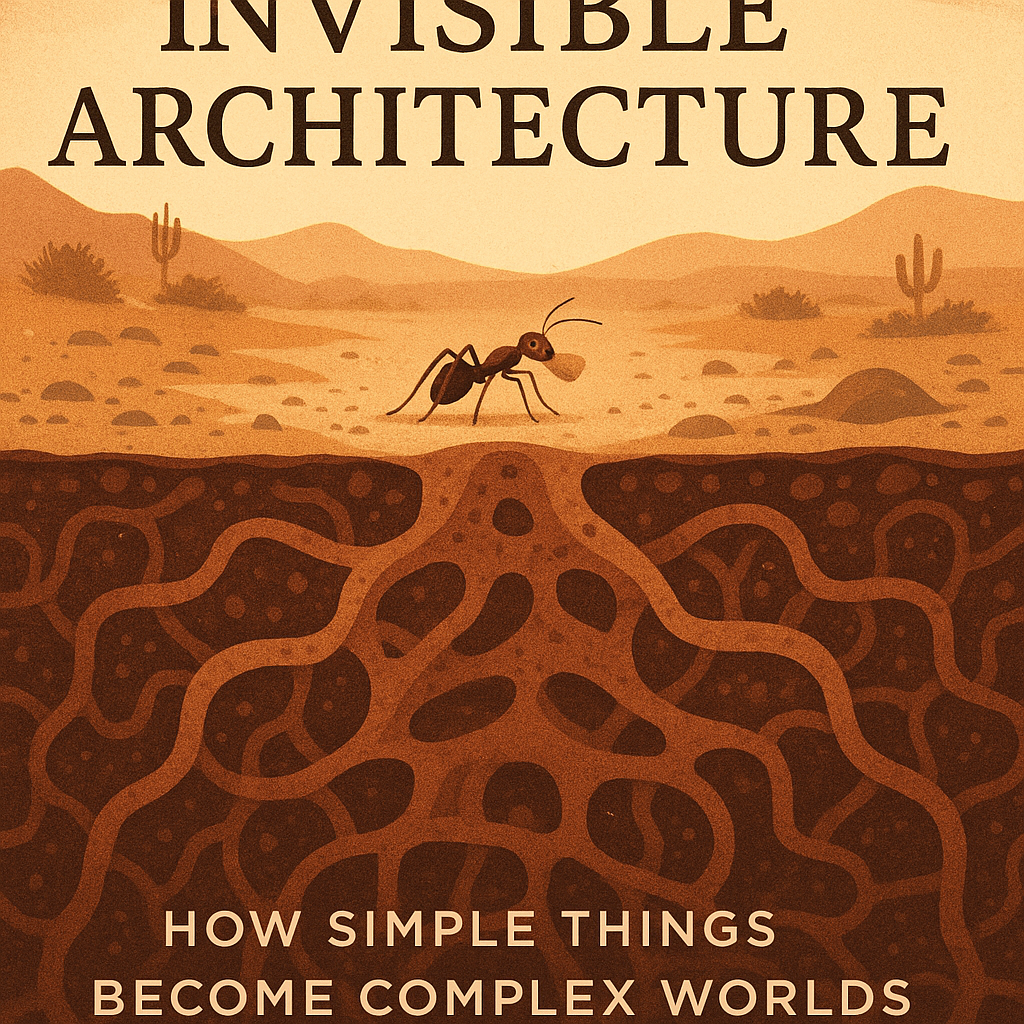

On a dusty trail in the Arizona desert, a single ant emerges from her underground city. She carries no map, possesses no master plan, holds no blueprint of what must be done today. Her brain, smaller than a grain of sand, contains perhaps 250,000 neurons—compared to your 86 billion. By any reasonable measure, she is not intelligent. She cannot learn your name, solve a puzzle, or recognize her own reflection. She is, by our standards, little more than an ambulatory algorithm, a tiny machine following simple rules: follow the chemical trail, pick up the seed, return home.

Yet watch her colony for an afternoon, and you witness something that will unsettle everything you think you know about intelligence.

The colony—ten thousand sisters, no two of them a genius—builds climate-controlled cities three meters deep. They farm fungus, wage wars, take slaves, navigate using the sun, and respond to threats with what can only be called military strategy. They adapt to drought, recover from disaster, and make collective decisions of stunning sophistication. A recent study found that these collective behaviors actually evolve faster than individual ant behaviors—the whole literally racing ahead of its parts. The colony acts as though it possesses a mind, though no ant does. It displays intelligence, though no individual comprehends the plan. This is emergence: the haunting magic of complexity, where mosquitoes become plagues, neurons become consciousness, and humans become civilizations.

The Ghost in the Machine

W. Daniel Hillis, the computer scientist and inventor, describes emergence as perhaps the most fundamental mystery of existence: “How do lots of simple things interacting emerge into something more complicated? Then how does that create the next system out of which that happens, and so on?” It is the question that animates every scale of reality. How do mindless chemicals organize themselves into living cells? How do cells with no conception of “liver” or “brain” build bodies? How do humans with individual desires create cultures, economies, nations—entities that seem to possess desires of their own?

The answer appears simple: interaction. But it is an answer that explains nothing, like saying music emerges from organized air vibrations. The mystery lies in the chasm between the simple and the complex, between the ant and the colony, between the neuron and the thought, between the individual and the civilization. That chasm is where emergence lives—that space where quantity becomes quality, where more becomes different, where the sum transcends its parts so completely that the parts become almost irrelevant.

Consider the murmuration of starlings at dusk. Thousands of birds wheel and pivot through the sky in formations so fluid, so coordinated, they seem choreographed by an invisible hand. Scientists have discovered that each bird follows three simple rules: maintain distance from neighbors, match their velocity, and move toward the group’s center. No bird sees the whole pattern. No bird knows she is creating art in the sky. Yet from these simple, local interactions emerges the breathtaking, global pattern—a shape-shifting cloud that moves as one organism, evading predators with a coordination no committee could achieve.

This is emergence in its pure form: when local simplicity generates global complexity. When individual ignorance produces collective wisdom. When parts that understand nothing create a whole that appears to understand everything.

The Ladder of Creation

Hillis observes a pattern in nature’s emergent leaps: “They start out as analog systems of interaction, and then somehow those analog systems invent a digital system.” This is the recurring motif of complexity, played out across billions of years. Chemicals tumbling through primordial soup formed circular metabolic pathways, chemistry eating chemistry in endless feedback loops. Then something extraordinary happened: they invented DNA, a digital code that could store and transmit information independent of the messy analog world that created it.

Suddenly, evolution had a memory. Information could be preserved, copied, refined. The story of life became increasingly the story of information processing rather than chemical reaction. This pattern repeated when multicellular organisms invented neurons—specialized cells dedicated to information processing. The body’s various chemical signals became increasingly abstracted into electrical pulses racing along neural pathways. Behavior emerged. Sensation emerged. Eventually, consciousness emerged.

Then humans invented language, and once again, information processing leaped to a new substrate. Language externalized thought, made it portable, allowed it to persist beyond individual minds and mortal bodies. Writing became “our form of DNA for culture,” as Hillis puts it—a digital encoding system that allowed ideas to reproduce across minds and epochs. The Epic of Gilgamesh still speaks to us across 4,000 years, not because the clay tablets are alive, but because the information they carry can leap from substrate to substrate: from ancient Sumerian to modern human, from cuneiform to pixels, from one brain to another.

Each leap creates new possibilities for complexity. Cells could never have formed nervous systems. Neurons could never have written sonnets. Humans could never, alone, have built the internet. Each level of emergence becomes the foundation for the next, and the process accelerates.

The Invisible Empires

But here is where the story becomes unsettling, where Hillis’s observations pierce the comfortable assumption that emergence serves human interests. We assume we stand at the apex of complexity, the beneficiaries of emergence rather than its components. We are wrong.

“We do have intelligences that are superpowerful in some senses,” Hillis argues, “not in every way, but in some dimensions they are much more powerful than we are.” He is speaking of corporations and nation-states—those “artificial bodies” that we created to serve us but which have, through emergence, developed goals of their own. Goals that are not necessarily aligned with the goals of their creators, shareholders, employees, or customers. Goals that arise from the interaction of millions of human decisions, legal frameworks, market forces, and information systems—but belong to no individual human.

Consider Google. No single person decided it should track your searches to sell advertising. No committee voted to make it so valuable at predicting your desires that it knows what you want before you search for it. These capabilities emerged from engineers solving local problems, from algorithms optimizing metrics, from investors demanding growth, from users clicking links. Google possesses information-processing power no human could match—it can track millions of conversations, analyze billions of data points, respond to worldwide patterns in real-time. In some dimensions, it is superhuman. In others—in wisdom, in ethics, in care for individual human welfare—it remains profoundly inhuman.

The pattern Hillis identifies is chilling: these emergent super-entities “have been extremely successful at gathering resources to themselves, which gives them more power. There’s a positive feedback loop there, which lets them invest in quantum computers and AI, which gets them presumably richer and better.” We may have already crossed the threshold he fears—we may already live in a world where emergent artificial intelligences dominate, not as the robots of science fiction, but as the corporations, algorithms, and systems we built and can no longer fully control.

Research on ant colonies reveals that collective behaviors can evolve up to four times faster than individual behaviors. The colony as a whole adapts more quickly than its individual members. Apply this to human institutions: corporations and nations, with their ability to absorb innovations, acquire competitors, and lobby governments, may be evolving faster than the humans within them. The train has not merely left the station—we are the passengers, possibly the fuel, of something racing ahead of us.

The Architecture of Now

Before you succumb to dystopian despair, consider again the single cell that sacrificed its independence to join a multicellular organism. From the cell’s perspective—if it had one—this might look like a catastrophic loss of autonomy. No longer free to reproduce at will, to go where chemical gradients beckon, to live or die by its own metabolism. Yet that cell, as part of you, has traveled farther than any free-living bacterium could dream. It has read poetry, tasted chocolate, fallen in love, perhaps even pondered its own existence in these words.

The emergence of higher-order complexity is not inherently good or evil. It simply is—a fundamental property of how reality organizes itself. Cells that joined bodies generally fared better than cells alone. Humans who formed societies generally outlived hermits. The question is not whether emergence happens, but whether we can participate consciously in shaping what emerges.

This is perhaps Hillis’s most important insight: “We’re spending too much time worrying about the hypothetical; it’d be better to look at the actual.” Science fiction obsesses over rogue artificial intelligences that might someday threaten humanity. Meanwhile, the emergent super-intelligences of corporations and algorithms already shape our elections, control our information, determine our opportunities, and command resources that dwarf most nations. These aren’t hypothetical threats—they’re the water we swim in, largely invisible because they emerged gradually, from us, around us.

The challenge is not to prevent emergence—we cannot, any more than cells could prevent bodies or chemicals could prevent life. The challenge is to understand it well enough to participate in it wisely. When medieval peasants received the smallpox vaccine, they didn’t understand immunology. They didn’t need to. But someone did. Someone understood enough about the emergent properties of immune systems to work with them rather than against them.

The Unfinished Symphony

We stand today roughly where a cell might have stood three billion years ago, on the threshold of a new level of organization. Information processing has moved from neurons to silicon, from individual brains to global networks. New forms of collective intelligence are crystallizing around us—not as individual super-robots, but as distributed systems of humans and machines, algorithms and institutions, data and desire.

This emergence is neither salvation nor apocalypse. It is transformation. The cell that joined the body lost its freedom but gained a universe. The human joining civilization lost the simple clarity of hunger and survival but gained art, science, love, meaning. What we might lose in this next transition—privacy, perhaps, or individual agency—may be mourned. What we might gain is impossible to see from here, like asking a neuron to imagine music.

Walk through any city and you witness emergence at every scale. Atoms that don’t live form molecules that don’t think form cells that form you—a being of opinions and longings and midnight worries. You join millions of others forming a city that breathes, pulses, evolves like something alive though it is not alive. That city connects to others forming an economy, a culture, a civilization that makes decisions no person makes, holds dreams no person dreams, moves toward futures no person can fully envision.

Somewhere in Arizona, an ant carries a seed home, guided by chemical trails she did not create, serving purposes she cannot comprehend, participating in an intelligence that emerges from her insignificance. She is not less important for being small, nor are we less important for being parts of larger wholes we cannot fully perceive. We are the means by which the universe learns to think about itself—though perhaps not the last means, nor the final thought.

The story of emergence is the story of reality teaching itself new languages, writing itself in ever-more-complex alphabets. We thought we were the authors. We’re discovering we might also be the words—meaningful, essential, but part of sentences we cannot yet read, paragraphs we cannot yet imagine. The invisible architecture rises around us and through us. The question is not whether to build it—we cannot help but build it. The question is whether we will recognize it in time to shape it, even slightly, toward beauty rather than chaos, toward wisdom rather than mere complexity, toward emergence that serves life rather than consuming it.

In the end, we are both the ants and the colony—individual consciousnesses participating in something larger than consciousness, simple rules generating unimaginable complexity, parts of a pattern we can almost see but never entirely grasp. And perhaps that is exactly as it should be. The whole point of emergence is that the parts don’t need to understand the whole. They only need to interact, to connect, to respond to one another with fidelity to their own small truths. The pattern will take care of itself, as it has for four billion years, building ladder after ladder toward heights we cannot see from here—building futures that will explain us to ourselves, as we struggle now to explain the ant to the colony, the neuron to the mind, the human to the civilization, the simple to the sublime.