Six Historical Trends of Declining Violence

Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature identifies six major historical trends that together chart a dramatic decline in human violence over time . Each trend marks a transition toward more peaceful forms of social organization and norms, with cumulative effects that have made modern societies markedly less violent and more cooperative than those of the past. Below we examine each trend, with examples of how they reduced violence and increased social harmony:

1. The Pacification Process

Pinker describes the Pacification Process as the transition from the anarchy of pre-state societies (hunter-gatherer or tribal horticultural groups) to the first agricultural civilizations with cities and central governments . In the “state of nature” before formal states, life was often violent—raiding, feuding, and warfare between clans or tribes were common. Anthropological studies and archaeological evidence suggest extremely high rates of violent death in many pre-state societies. For example, people living in early hunter-gatherer or tribal societies had a far greater chance of dying in intertribal warfare (on the order of 15% of the population) than people in the 20th century had of dying in war (on the order of 3% or less) . As early states (the first “Leviathans”) emerged in Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, Mesoamerica, and elsewhere, they imposed central authority and monopolized the use of force, which reduced the cycle of revenge killings and raiding. With rulers and laws to arbitrate disputes and punish aggression, the incentives for revenge or predatory violence (to use Pinker’s terms for inner demons) were curtailed by the threat of punishment . Over time, this pacification brought a several-fold decrease in rates of violent death as chronic feuding gave way to the rule of law . In short, the rise of governments with a monopoly on force (what Hobbes called the “Leviathan”) began to tame humanity’s worst violent impulses by making peaceful cooperation more beneficial than constant conflict .

2. The Civilizing Process

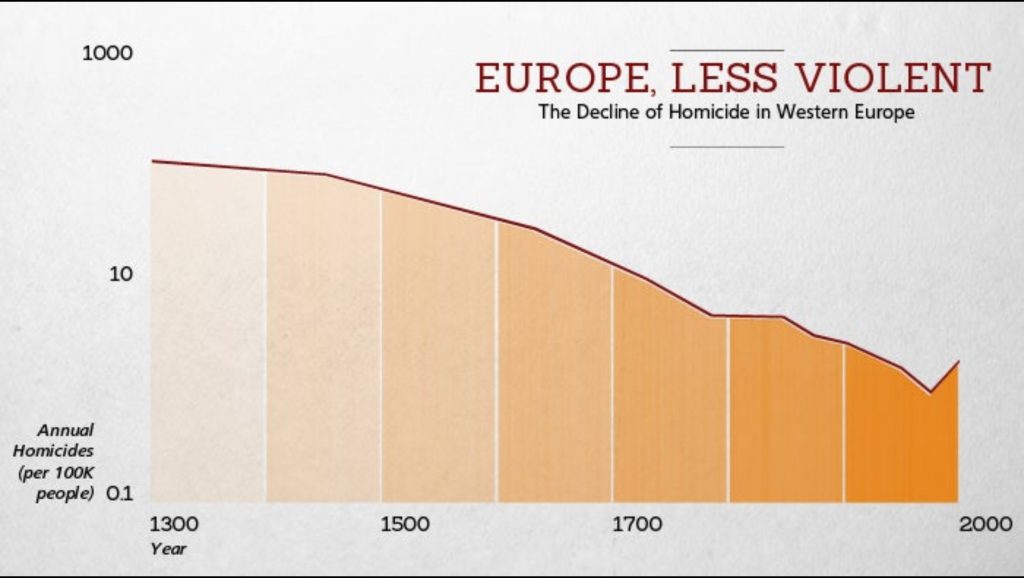

The Civilizing Process (a term Pinker borrows from sociologist Norbert Elias) refers to the long decline of violence from the late Middle Ages into modern times, particularly in Europe . As medieval feudal territories consolidated into larger kingdoms and eventually modern states with centralized authority, violence in daily life sharply diminished. Historical records show that homicide rates in Western Europe fell dramatically—by a factor of ten to fifty—between around 1300 and the 20th century . This decline is illustrated by the plummeting homicide rate in countries like England, the Netherlands, Germany, and Italy over these centuries (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Homicide rates per 100,000 people in Western Europe, 1300–2000, declined roughly 10- to 50-fold from medieval times to the modern era . Centralized justice systems replaced private vengeance; the widespread carrying of weapons was gradually curtailed; and social norms shifted to reward self-restraint and polite conduct. For example, practices like dueling to defend one’s honor were eventually outlawed or fell out of fashion, and cruel punishments (such as breaking on the wheel or burning at the stake) were eliminated as sensibilites changed during the Enlightenment. In everyday behavior, people became more refined in manners and more reluctant to resort to violence – a transformation Elias described as the spread of civilized norms. Pinker notes that this era saw Europeans “[develop] a culture of self-control, courtesy, and respect for life” that coincided with tightening state control over violence . In essence, the civilizing process combined stronger state authority with evolving social norms that valorized the better angels of self-control and empathy, leading to precipitous drops in violent crime and brutality in society .

3. The Humanitarian Revolution

The Humanitarian Revolution unfolded on a shorter timescale (primarily in the 17th–18th centuries) during the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment . During this period, a wave of intellectual and moral changes led to the first organized movements to curb institutional violence and cruelty. Enlightenment thinkers and reformers, driven by reason and a new moral outlook, began to challenge practices that had long been taken for granted. Pinker (citing historian Lynn Hunt) notes that this era saw the abolition of barbaric customs such as judicial torture, human sacrifice, and animal cruelty, as well as campaigns to end slavery, dueling, sadistic punishment, and superstitious killings (like witch-hunts) . For example, Cesare Beccaria’s 1764 treatise On Crimes and Punishments argued against torture and the death penalty on rational humanistic grounds, influencing penal reform across Europe. Similarly, movements to abolish slavery gained momentum in the late 18th century – the British abolition of the slave trade in 1807 and slavery itself in 1833, and the rise of abolitionism in America, reflected a growing consensus that slavery was morally abhorrent. A new moral sense was emerging that recoiled at cruelty and championed universal human rights. This humanitarian fervor was fueled by empathy as well: for instance, widely read novels and memoirs (such as Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the 19th century) helped readers empathize with the suffering of slaves or the condemned, bolstering abolitionist and anti-torture sentiments. The cumulative effect of the Humanitarian Revolution was a sweeping reduction in cruel practices that had once been common: public executions and torture waned, slavery began to disappear, and people increasingly condemned bloodsports and corporal punishment. In Pinker’s view, this marked a triumph of humanity’s “better angels” (empathy, reason, and moral sense) over some of our “inner demons” (sadism, dominance, and ideology), enshrining respect for human life and dignity as core values . It set the stage for further declines in violence in subsequent centuries by embedding anti-violence principles into law and culture.

4. The Long Peace (Post–World War II)

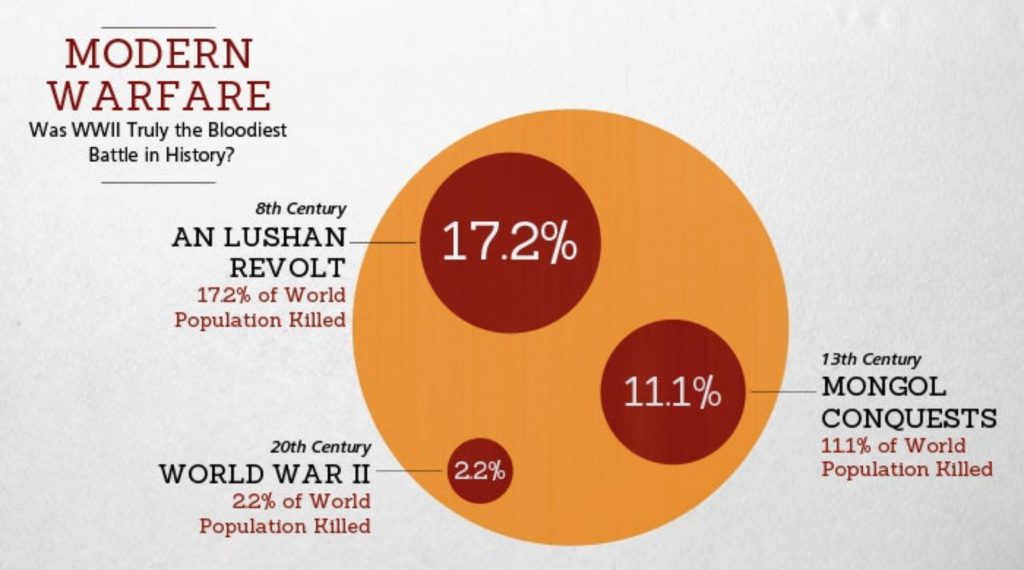

Pinker uses the term “The Long Peace” (coined by historian John Lewis Gaddis) to describe the remarkable absence of wars between the great powers since the end of World War II in 1945 . In the first half of the 20th century, two world wars killed tens of millions and traumatized the globe. Yet in the aftermath, despite high geopolitical tensions (e.g. the Cold War), the largest nations have not fought each other directly on the battlefield. There has been no repeat of the world wars; former arch-rivals in Europe became integrated through the European Union and NATO, relying on diplomacy and economic ties instead of war. The United States and Soviet Union, while locked in an ideological Cold War, avoided direct conflict partly due to nuclear deterrence (the horrific prospect of mutually assured destruction imposed a rational caution). More broadly, the latter half of the 20th century saw a steep decline in interstate wars and conquests. Whereas in earlier centuries it was routine for major powers to go to war once a generation or for empires to expand by force, since 1945 borders have barely changed by violent conquest. The statistics reflect this peaceful trend: battle deaths worldwide fell dramatically after World War II (aside from a spike during mid-century conflicts like Korea and Vietnam) and have stayed relatively low . Notably, while World War II was the deadliest conflict in absolute numbers, as a percentage of world population it was far from the worst – earlier conflicts like the 8th-century An Lushan Revolt or the Mongol conquests killed larger fractions of the population . Figure 2 illustrates this point by comparing World War II’s toll (~2.2% of world population) to those earlier wars.

Figure 2: The deadliest conflicts in history by share of world population killed – e.g. the 8th-century An Lushan Revolt (17.2%) and 13th-century Mongol conquests (11.1%) far exceeded World War II (2.2%) in relative impact . This highlights that modernity’s worst war, despite its absolute carnage, was proportionally less devastating than many pre-modern wars. The “Long Peace” can be attributed to several reinforcing factors: the Leviathan of stable nation-states and international bodies (like the UN) discouraging aggression through law and deterrence ; the rise of commerce and globalization making war unprofitable ; the spread of democracy, since democracies rarely fight each other and tend to negotiate disputes ; and a post-WWII normative change that stigmatizes imperialism and glorifies peace. This period has seen unprecedented cooperation among major powers and a growing respect for universal human rights, which together have kept large-scale warfare at bay for three-quarters of a century.

5. The New Peace (Post–Cold War)

Pinker labels the period since the end of the Cold War in 1989 as the “New Peace.” This trend, while “more tenuous” than the Long Peace, is characterized by a worldwide decline in organized armed conflicts of all kinds: not just wars between great powers (which were already rare after 1945), but also civil wars, genocides, ethnic conflicts, and terrorist attacks have all shown a decreasing trend since the late 20th century . After the fall of the Iron Curtain, many proxy wars and insurgencies fueled by superpower rivalry wound down. The 1990s and 2000s saw peace settlements in longstanding conflicts (e.g. the end of major civil wars in Central America, southern Africa, and Southeast Asia) and international efforts to prevent or limit new wars. Although tragic conflicts did erupt (such as genocides in Rwanda and the wars in the former Yugoslavia), these were relatively contained geographically and eventually drew international intervention and rebuilding efforts. Overall, the frequency and death toll of conflicts per capita continued to drop after 1989 . Pinker acknowledges that this “New Peace” is not absolute – terrorism and regional wars (e.g. in the Middle East) remain concerns – but statistically, the post–Cold War era has been comparatively peaceful by historical standards. He credits factors like the strengthening of international peacekeeping, the spread of global norms against aggression (e.g. the “Responsibility to Protect” doctrine), and the continuing effects of commerce and democratization even in developing regions. In sum, the New Peace extends the Long Peace’s legacy beyond the superpowers, contributing to a world in which war and mass violence have become rarer and more universally condemned than ever before.

6. The Rights Revolutions

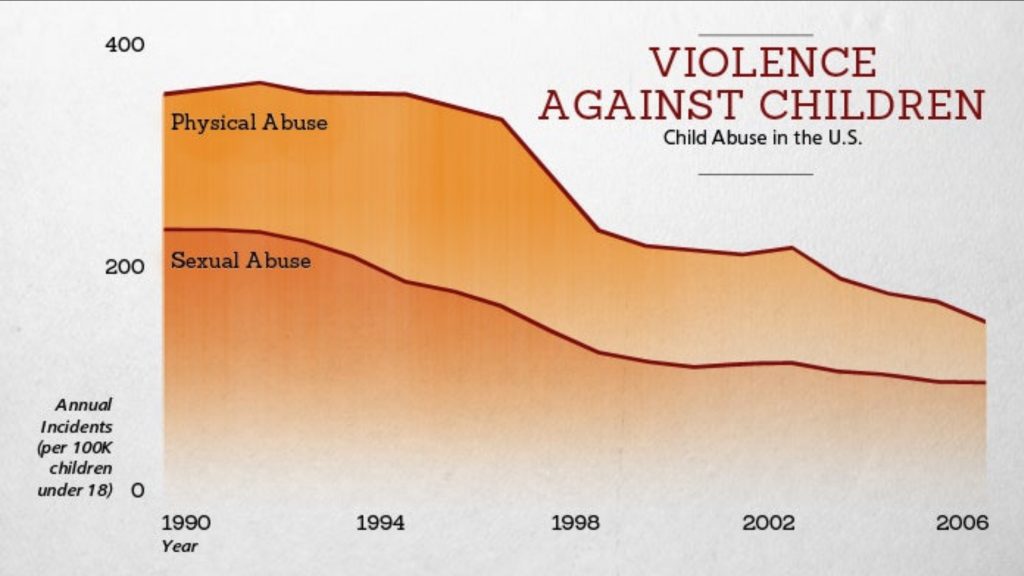

The final trend Pinker highlights is the set of Rights Revolutions that unfolded from the late 20th century into the 21st. These include the civil rights movement, the women’s rights/feminist movement, the children’s rights movement, the gay rights movement, and even an animal rights movement . Each of these revolutions expanded humanity’s circle of moral concern and further humanized societal values and laws. For example, the civil rights movement in the 1950s–60s United States (and parallel anti-colonial and anti-racist movements worldwide) delegitimized racial violence such as lynching and state-sanctioned discrimination, leading to steep declines in racially motivated violence. The women’s movement challenged domestic violence, marital rape, and unequal treatment; behaviors like wife-beating, once casually tolerated, became socially and legally unacceptable. Indeed, attitudes toward domestic violence changed radically: for centuries, corporal punishment of wives and children was considered a man’s prerogative, but by the late 20th century it came to be seen as a serious crime. In one U.S. survey in 1995, 87% of respondents said police intervention is necessary when a man beats his wife, whereas in earlier eras such intervention was rare . Likewise, the children’s rights revolution has led to huge declines in violence against children – between 1990 and 2007, physical abuse of children in the U.S. fell by more than half, and sexual abuse by around two-thirds . Figure 3 shows this sharp drop in child abuse rates over that period.

Figure 3: The incidence of physical and sexual abuse of children in the U.S. declined dramatically from 1990 to 2006 , reflecting increasing societal commitment to children’s rights and safety. The gay rights movement, particularly since the 1970s, has similarly reduced hate crimes and violence against LGBTQ individuals by changing laws (e.g. hate-crime statutes, decriminalization of homosexuality) and public attitudes. Even animals benefited: practices like animal cruelty and blood sports (dogfighting, cockfighting) have been outlawed in many countries, and there is growing aversion to needless harm to animals . These “rights revolutions” all share a common thread: a “growing revulsion against aggression on smaller scales” and an expansion of empathy and moral concern to marginalized groups . They were often inspired by one another – for instance, the success of the civil rights movement informed later movements for women’s and gay rights, each adopting similar tactics and moral arguments . Collectively, the rights revolutions entrenched norms of tolerance, equality, and respect for the dignity of every person (and even animals), which in turn have led to measurable declines in many forms of violence and mistreatment . Society became less violent not only in the aggregate (fewer wars and homicides) but also at the everyday level – from the household to the schoolyard – as these rights-based values took hold.

Five Inner Demons: Human Propensities for Violence

If the six trends above describe what has happened (a decline in violence), Pinker’s analysis of five “inner demons” delves into why violence was so common in the first place and what motivates humans toward aggression . These inner demons are evolved psychological systems or motives that can incline people to violence under certain circumstances . They are not a single “death instinct,” but rather distinct drivers like greed, ego, or fear, each with its own logic . Understanding these five inner demons is key to seeing how violence has been curtailed over time – because each demon has, to varying degrees, been checked or counteracted by societal changes and our “better angels.” Here are Pinker’s five inner demons, with historical illustrations of their influence and notes on how they’ve been tamed:

1. Predatory or Practical Violence: This is violence as a means to an end – essentially using aggression instrumentally to achieve some gain (resources, power, security) . Examples abound throughout history: a mugger using force to steal a wallet, or at the large scale, empires waging war to seize land and wealth. Colonization and conquests often had a predatory aspect (e.g. the European powers’ scramble for Africa was driven by the practical goal of obtaining resources and strategic advantage, at the expense of indigenous populations). In the state of nature, predatory violence could be rational – attacking others before they attack you, or raiding a neighboring village to take its fertile fields, might enhance one’s survival or reproductive success. However, over time external forces have curtailed predatory violence by changing its cost-benefit calculus. The rise of strong states (Leviathans) made private violence less profitable: a thief or conqueror now faces jail or death at the hands of a larger authority. Commerce and trade also reduced the appeal of predation: why risk violence to steal resources when one can acquire goods more safely through trade? As Pinker notes, the “interdependence among nations through commerce” gave societies “more to gain through peaceful cooperation than through war and competition” . Thus, while the predatory impulse remains part of human nature, successful modern societies channel it into nonviolent competition (business, innovation) and punish or deter those who would use force for gain.

2. Dominance: The dominance demon is the urge for power, status, and glory – the drive to climb the social hierarchy and assert authority over others . In individuals, it can manifest as bullying or tyrannical ambition; in groups (ethnic, religious, national), it emerges as quests for supremacy or honor. History is replete with dominance-driven violence: emperors and kings waged wars of conquest to expand their glory, feudal lords dueled to defend their honor, and gang leaders fight turf wars to maintain dominance. Even the horrific wars of the 20th century had elements of dominance seeking – for instance, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi regime were motivated in part by a desire for Aryan racial supremacy and national domination. Pinker argues that dominance motivations are deeply rooted in our evolutionary past (e.g. male competition for leadership and mating opportunities) and can be triggered in the right social conditions . However, in recent history humanity has found ways to rein in the dominance motive. The establishment of democracy is one: instead of violent power struggles, leadership transitions occur via elections and institutional checks, channeling the dominance motive into politics bounded by law. Successful democracies make zero-sum dominance contests less lethal by enforcing rules (no assassinating rivals, for example) and emphasizing equality under the law. Social norms have also turned against naked displays of dominance – for instance, schoolyard bullying and domestic abuse (domineering a spouse or child) are now widely condemned. The feminization of society (greater influence of women and values stereotypically associated with women, like caring and compromise) may have helped here, since on average women exhibit less dominance-driven violence; as women’s status has risen, political and social cultures often become less obsessed with machismo and honor-based violence . Additionally, international norms after World War II have delegitimized wars of conquest – a country seeking dominance risks economic and diplomatic isolation. In short, while the craving for prestige or power hasn’t vanished, modern institutions and values have tended to deflate the dominance demon by making humility, cooperation, and legal processes more rewarding than violent glory-seeking.

3. Revenge: This inner demon is the moralistic urge for retribution – the instinct to retaliate against harm with harm . Revenge has ancient evolutionary logic: a credible threat of vengeance can deter would-be aggressors, and in small societies, not retaliating could signal weakness. As a result, cycles of vendetta were extremely common in earlier times. Think of the famous feuds of history (the Montagues vs. Capulets in Shakespeare, or the real-life Hatfields vs. McCoys) where blood spills for generations in tit-for-tat killings. Many cultures developed strict honor codes compelling people (especially men) to answer any insult or injury with violent payback. In medieval Europe, if someone killed your kin, honor dictated you take revenge unless compensated by weregild; similarly, in tribal societies lacking state police, justice was often a family or clan responsibility, leading to endless feuds. The revenge impulse is still with us – people feel a visceral satisfaction at seeing wrongdoers punished, and it can flare up in everything from road rage (“he cut me off, I’ll show him!”) to ethnic pogroms after a terrorist attack. However, one of the great civilizing triumphs has been to domesticate revenge by replacing it with formal justice. As Pinker emphasizes, the Leviathan (a strong state with courts and police) takes over the role of punisher: instead of avenging a murder personally, victims’ families are (in theory) satisfied by the murderer being tried and imprisoned by the state . This rule of law short-circuits the self-perpetuating cycles of vengeance, bringing violence down. Philosophically and morally, there’s also been a shift: forgiveness and reconciliation are now often prized over revenge. Modern legal systems focus on proportional punishment and rehabilitation rather than brutal revenge. Moreover, the escalator of reason and humanistic ethics have led many to question blood-for-blood mentalities; for instance, movements to abolish the death penalty argue that state-sanctioned killing for retribution is uncivilized. In summary, while the revenge impulse still exists, it is far less likely to govern our actions today because we have cultural narratives and institutions that insist “two wrongs don’t make a right” and that legitimate justice should be impartial and restrained, not an angry mob with torches.

4. Sadism: Sadism is the drive to inflict pain for pleasure – the demon that enjoys cruelty for its own sake . Of the five inner demons, sadism is perhaps the most viscerally disturbing and thankfully one of the rarer motivations. Yet history has known true sadists: from Roman emperors delighting in throwing Christians to lions, to medieval torture enthusiasts, to serial killers in modern times. Ordinary people can also be seduced into casual sadism in certain environments – for example, lynch mobs in the American South took a perverse glee in the torture of their victims, and some concentration camp guards in the Holocaust were noted to sadistically torment prisoners. Public executions and cruel punishments in past centuries often had an element of spectacle, essentially turning pain into entertainment. So how has sadistic violence been curtailed? Largely through the Humanitarian Revolution and changing social norms. As Enlightenment humanism spread, intellectuals began to argue that cruelty is itself the ultimate evil. By the 19th and 20th centuries, acts of wanton cruelty started to provoke public horror rather than applause. The decline of practices like bear-baiting, cockfighting, and torture-as-entertainment reflected this moral progress – people were no longer willing to tolerate suffering as spectacle. In modern times, anyone caught deriving pleasure from cruelty (say, abusing animals or bullying peers) is seen as having a psychological problem, not as a normal person having fun. The criminal justice system has also become more attuned to punishing those who commit acts of torture or extreme cruelty. Empathy and moral sense – two of our better angels – work directly against sadism, as more people learn to see the victim’s pain through their eyes and feel revulsion rather than delight. Even media and literature, by dramatizing the suffering of victims, have fostered identification with the victim rather than the perpetrator. Thus, while sadism has not disappeared from the human condition, society strongly suppresses it: sadists seldom find social approval or institutional support today, whereas in earlier eras some forms of cruelty were socially accepted or even encouraged. The result is a drop in violence that is purely cruel (hate crimes, torture, etc.), reinforcing an atmosphere of greater compassion in society.

5. Ideology: Perhaps the most formidable inner demon is ideology – a set of beliefs, often utopian or fanatically moral, that can justify unlimited violence in pursuit of an ostensibly “good” cause . Pinker notes that ideologies (nationalist, religious, political) have fueled many of history’s worst episodes of violence, because they align the other demons toward a common destructive goal. When people believe they are fighting for a grand ideal – God’s will, racial purity, class equality, national glory – they may feel licensed to commit atrocities that they would never do for personal gain alone. The Crusaders who massacred whole cities, the Inquisitors who tortured heretics, the revolutionaries and dictators of the 20th century who engineered genocides and mass repression (from the Holocaust to Stalin’s purges to Mao’s Cultural Revolution) all drew moral fervor from ideologies. Under the spell of ideology, revenge becomes righteous vengeance against “evil” groups, dominance becomes the glory of one’s creed or nation, and even sadism can be reframed as purifying the world through others’ suffering. Ideologies often carry a utopian vision that the ends justify any means – a recipe for unrestrained violence. Curtailing ideological violence has been a great challenge, but progress has come through several avenues. First, the modern world has seen a rise of pluralism and secularism which undercut the appeal of absolutist dogmas – many societies are less homogeneous and less governed by a single orthodox ideology than in the past, making it harder to mobilize everyone for a fanatical cause. Second, the “escalator of reason” (discussed below) has made people more skeptical of doctrines that demand bloodshed; education and open debate allow more citizens to detect the logical flaws and human costs of extremist ideologies. For example, in the post-WWII era, the horrors of Nazi and Stalinist regimes served as cautionary tales that discredited those totalizing ideologies. Likewise, increased cosmopolitan exposure – through travel, the internet, diverse communities – humanizes the supposed “enemy” groups and makes it harder to demonize them as ideology often requires . Internationally, ideologies like aggressive nationalism have been checked by institutions (the UN, EU, etc.) that emphasize cooperation and human rights. While new ideologies can arise (e.g. extremist religious terror groups in the 21st century), the global response has generally been quick condemnation and multilateral action, reflecting a global norm that large-scale ideological violence is unacceptable. In summary, though ideology as a motivator for violence is ever-present, the modern world’s emphasis on reason, diversity, and universal values has begun to hem it in. By learning from the past and promoting open societies, humanity has put cracks in the ideological armor that too often justified rivers of blood.

Four Better Angels: Restraints on Violence

Against the dark impulses of the inner demons stand our “better angels” – the facets of human nature that incline us away from violence and toward cooperation and peace . Pinker identifies four major motives or capacities that can check our violent urges: Empathy, Self-Control, the Moral Sense, and Reason . These are not saints whispering in our ears, but rather ordinary parts of human psychology that, when nurtured by society, steer us to treat each other with compassion and restraint. Crucially, the better angels are what have been amplified over history by the trends and forces discussed in this report. Below we detail each “angel,” with real-world examples and research illustrating their role in promoting pro-social behavior and reducing violence:

1. Empathy: Empathy is our ability to feel and understand others’ emotions – to literally share in another’s pain or joy . This emotional mirroring prompts us to align others’ interests with our own, making it psychologically harder to harm them. Empathy extends the circle of caring beyond the self. In practice, empathy has been a powerful driver of humane behavior. For example, the abolitionist movement was fueled in part by empathetic appeals: stories of enslaved people’s suffering (in narratives like Uncle Tom’s Cabin or the autobiography of Frederick Douglass) stirred readers’ compassion and galvanized anti-slavery sentiment. Likewise, public outrage at child labor in the early 20th century grew as journalists like Lewis Hine showed photographs of the miserable, dangerous conditions children endured – people could see themselves in those children, and laws changed to protect kids. Psychological research supports empathy’s role in reducing aggression: studies find that when people are encouraged to take another’s perspective, they are less likely to inflict pain or punishment. Empathy has also expanded over history. As literacy and education rose (one of Pinker’s historical forces), people began consuming novels and journalism that put them in others’ shoes – including those of different races, genders, or nationalities. This contributed to what philosophers call the expanding circle of moral concern. For instance, 19th-century readers of Dickens were led to empathize with the poor, influencing early social reforms; in the 20th century, seeing televised images of war victims or famine victims on the other side of the world tugged at heartstrings and spurred humanitarian aid. Pinker emphasizes that the cosmopolitanism of the modern age – travel, global media, and the mixing of cultures – has heightened empathy by making “others” more familiar . As people empathize with broader categories (not just family or tribe but all human beings, even animals), the threshold for committing violence rises. Of course, empathy has limits – it can be selective or even weaponized (empathy for one’s in-group can fuel anger toward an out-group) – but on the whole, the cultivation of empathy has been a civilizing force. It underlies charitable behavior, peacemaking efforts (empathizing with an enemy’s perspective can help resolve conflict), and the modern concern for human rights. In sum, empathy is a key “angel” that softens our hearts and connects us to one another, making cruelty more difficult and compassion easier.

2. Self-Control: Self-control is the capacity to restrain our impulses, to anticipate consequences, and to act with foresight rather than aggression . Many acts of violence are impulsive – a bar fight sparked by a moment’s anger, an insult answered immediately with a punch. The ability to regulate these flashes of anger or temptation is crucial for peaceful coexistence. Over the long arc of history, societies have increasingly emphasized self-control in their citizens. For example, Norbert Elias’s research (which Pinker cites) showed that as European society “civilized,” people placed greater importance on controlling emotions like anger and practicing polite restraint in public . Parents and schools began teaching children to “use your words, not your fists,” which is essentially a lesson in impulse control. The decline of practices like dueling or spontaneous brawling among gentlemen came about because cultural norms shifted to view such loss of control as disgraceful rather than honorable. Psychologically, humans do have a built-in capacity for self-control (governed by brain systems in the prefrontal cortex), but it can be strengthened or weakened by environment. Research on the “marshmallow test” (a famous study in delaying gratification) suggests that those with better self-control in childhood have more positive social outcomes and fewer tendencies toward aggression in later life. Recognizing this, modern institutions often seek to improve self-control: anger-management programs, rehabilitation for violent offenders, and even meditation or mindfulness training (which many schools now introduce) are ways to help individuals pause and think instead of lashing out. Reason and moral sense support self-control by providing internal guard rails (e.g. thinking “If I punch this person, I’ll regret it” or feeling “It’s wrong to hit even if I’m mad”). Meanwhile, external structures like law enforcement also incentivize self-restraint (knowing that a violent outburst could lead to arrest is a deterrent that forces a moment’s reflection). Over centuries, the general increase in self-control has paid off in lower rates of violence: for instance, modern homicide rates are not only lower due to policing, but because far fewer interpersonal disputes escalate to lethal violence in the first place – people today are more likely to walk away or calmly negotiate than to pull a knife over an insult. Pinker would argue this improvement is partly because our better angel of self-control has been culturally magnified, making us, on average, less hot-headed than our ancestors.

3. Moral Sense: Humans have a moral sense – a set of norms and intuitions about right and wrong that can guide behavior away from violence . This can include notions of fairness, justice, sanctity of life, and so on. Our moral sense is shaped by culture and can be a double-edged sword: it sometimes reduces violence (for example, “Thou shalt not kill” is a moral rule that obviously inhibits violence), but in other cases a warped moral code can increase violence (e.g. a tribal or authoritarian moral code that says “It’s righteous to kill members of an impure group” can fuel violence) . Pinker acknowledges this paradox, noting that moral norms can sanctify peace or, alternatively, sanctify war (such as “holy war” ideologies) . The encouraging fact is that over time, moral codes have become less tribal and more universal. The dominant moral frameworks in many societies today emphasize human rights, equality, and nonviolence. Consider how the idea of justice has evolved: medieval justice often meant brutal punishment of wrongdoers (public executions for minor theft, for instance, which were seen as morally proper then), whereas modern justice aspires to rehabilitation and measured punishment, reflecting a moral view that values every human life. The spread of Enlightenment values – liberty, tolerance, the notion that all individuals have inherent dignity – embedded a non-violent ethic into institutions like law, government, and education. For example, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) is essentially a moral charter that rejects violence such as torture, slavery, and cruel punishment as violations of fundamental human values. This worldwide moral commitment helps pressure even authoritarian regimes to curtail their worst violence (nations do not want the stigma of being seen as human-rights abusers). On a smaller scale, many people’s personal moral sense has expanded; things that were once morally acceptable (hitting children, dueling for honor, treating one’s wife as property) are now widely seen as immoral. Pinker would likely attribute these shifts to the aforementioned rights revolutions and humanitarian trends reinforcing a moral abhorrence of violence. Additionally, religions and philosophies have often served to promulgate moral rules that discourage violence – e.g. Buddhism’s principle of ahimsa (non-harm), Christianity’s teachings of compassion and forgiveness (notwithstanding historical religious violence, many believers today interpret their faith as mandating peace). The key point is that when the better angel of our moral sense is educated and directed toward inclusive, nonviolent values, it becomes a powerful brake on violent behavior. It makes people internally govern themselves with sentiments like guilt, shame, or indignation at the thought of harming others. The result is a society where more people do the right thing not just out of fear of punishment, but because their conscience tells them to.

4. Reason: The faculty of reason – our ability to use logic, evidence, and rational reflection – is Pinker’s fourth better angel . Reason can override our impulses and biases by allowing us to step back and think objectively. Throughout history, appeals to reason have often been used to quell violence. One aspect of reason’s contribution is self-interest properly understood: rationally, endless feuds or wars are negative-sum games that ruin all parties, whereas peace and cooperation are positive-sum (everyone benefits more). As societies became more interdependent and educated, more people began to recognize the futility of constant violence. For instance, Enlightenment philosophers (Kant, Paine, Voltaire, etc.) made rational arguments against practices like torture, tyranny, and war – they pointed out that such violence was not only immoral but irrational in failing to maximize human well-being. These arguments did gain traction, helping to usher in reforms (e.g. Beccaria’s rational critique of torture led to its abolition in many places, as noted earlier). Reason also helps us see through false narratives that fuel violence. Consider dueling: for centuries, it persisted because of an irrational honor code. Eventually, people reasoned that it was absurd to risk death over an insult, and society agreed that legal courts or mere words could settle disputes – that’s reason overcoming a violent cultural norm. On a larger scale, the 20th century’s close brushes with apocalypse (World War II’s unprecedented destruction, the prospect of nuclear war) forced leaders and citizens to think rationally about the costs of conflict. The Cold War’s strategy of deterrence was an exercise in grim rationality to prevent violence: both sides had to acknowledge it was in neither’s interest to start a nuclear war. Moreover, reason underlies scientific and philosophical progress that indirectly reduces violence: for example, as scientific reasoning debunked racist pseudoscience, it removed some ideological justification for racial violence; as economic reasoning showed the benefits of trade, it made war for plunder seem less sensible than commerce. Pinker calls the increasing application of knowledge and rationality to human affairs the “Escalator of Reason,” suggesting that as humanity climbs this escalator, it sees ever more clearly the folly of violence . One can also see reason at work in the creation of international law and organizations – these are rational, negotiated frameworks to handle disputes without bloodshed. None of this implies humans are perfectly rational (far from it), but it does mean that our capacity for thought can check our capacity for bloodlust. When cooler heads prevail in a heated situation, that’s reason taming emotion. When a community chooses to engage in dialogue and compromise rather than go to war, that’s reason guiding collective decision-making. In Pinker’s thesis, the spread of literacy, education, and enlightenment ideals has gradually empowered this better angel, making us on average more likely to settle conflicts with words and ideas rather than fists and swords . In combination with empathy, self-control, and moral sense, reason helps form a “bootstrap” by which civilization lifts itself to higher ground, curbing violence and promoting peace through understanding and solutions rather than force.

Five Key Historical Forces Driving Peace

Having detailed the trends (outcomes) and the psychological traits (demons and angels) at play, Pinker’s framework also highlights five key historical forces that have pushed the world in a more peaceful direction . These are broad, long-term forces – societal changes or institutions – that manage or harness our inner demons and amplify our better angels, thereby suppressing violence. Each force can be seen as a dynamic process that alters the environment in which our violent or peaceful inclinations manifest. Pinker argues that these five forces, often interacting with each other, are fundamental in explaining why violence has declined. They are: the Leviathan, commerce, feminization, cosmopolitanism, and the escalator of reason . We examine each in turn:

1. The Leviathan (Strong State Governance): “Leviathan” is Thomas Hobbes’s term (from his 1651 work Leviathan) for a powerful state – an authority with a monopoly on the legitimate use of force. Pinker adopts this concept to explain how effective governance dramatically reduces violence . When a neutral central authority can enforce laws, arbitrate disputes, and punish aggressors, it dissuades people from taking the law (or revenge) into their own hands . The Leviathan’s presence turns zero-sum conflicts into orderly legal matters. Historically, the expansion of state authority was pivotal in ending pervasive feuding and banditry; for example, as medieval European kings consolidated power, they suppressed the feuds and private wars of the feudal lords, leading to a significant drop in aristocratic violence. In modern times, we see stark contrasts between areas with strong governance and those without: regions of the world with weak or failed states (where no one reliably punishes crime or rebellion) often descend into chaos and civil war, whereas regions with stable governments maintain peace. Pinker notes that inept or absent governance is one of the biggest risk factors for violence, explaining much of the difference in violence levels between parts of the developing world and the more peaceful developed world . The Leviathan, when functioning well, keeps the inner demons of dominance and revenge in check by making personal coercion prohibitively costly . It also can protect the vulnerable (enforcing laws against domestic violence, for instance, empowers victims and deters would-be abusers). However, it’s worth noting that an unchecked Leviathan can itself become violent or tyrannical – Hobbes’s solution has a dark side if the state turns predatory. Pinker’s argument emphasizes democratic and accountable Leviathans: governments that embody the will of the people and maintain rule of law, rather than arbitrary despotism . Such states not only tamp down internal violence (through police and courts), but also reduce external war – democracies rarely fight each other, and effective states have less to gain and more to lose from war. In sum, the spread of strong, responsible government authority worldwide – from the first agrarian kingdoms to today’s international-law-abiding states – has been a fundamental force pulling us away from the bloody anarchy of the past and toward a more peaceful order.

2. Commerce (Gentle Commerce and Interdependence): The second force is the rise of commerce, trade, and economic interdependence as a dominant mode of interaction between groups . The idea, which dates back to Enlightenment thinkers like Montesquieu and Adam Smith, is sometimes called “doux commerce” (gentle commerce): the notion that trade pacifies relations because it’s mutually beneficial. Pinker argues that as societies engage more in commerce, they see other groups more as trading partners than as targets for plunder . War and violence become economically irrational when you can gain more by exchanging goods and services. Historically, the growth of market economies and international trade in the 18th and 19th centuries coincided with a decline in interstate wars in Europe (especially after the Napoleonic Wars, when the “Concert of Europe” fostered diplomatic solutions). In the late 20th century, globalization took commercial interdependence to new heights: countries with tightly intertwined economies (for example, the nations of the European Union, or the U.S. and China today) have a powerful incentive to maintain peaceful relations, since conflict would disrupt prosperity for both sides. There’s empirical support for this pacifying effect of trade – many political scientists find that economically interdependent states are less likely to go to war with each other. Commerce also fosters internal peace by giving individuals and groups an alternative to violent appropriation; you don’t need to rob your neighbor if you can earn money and buy goods lawfully. Moreover, engaging in commerce can expand one’s perspective: a merchant has to understand the customs and needs of others to trade successfully, which can build a cosmopolitan outlook. Pinker notes that commerce is one factor that has “given [nations] more to gain through peaceful cooperation than through war and competition” . This aligns self-interest with peace. It’s important to recognize, however, that commerce alone doesn’t guarantee harmony (World War I broke out despite robust trade in Europe) – yet, combined with other forces, commerce has generally made violence less appealing. We can see its influence in the modern reluctance of countries to jeopardize global markets with conflicts, and in the way sanctions (a tool of economic pressure) are now often used instead of bombs to resolve disputes. In essence, the spread of capitalism and trade networks made people and nations materially dependent on each other, and thus incentivized them to keep relations civil and rules-based, reinforcing the overall decline in violence.

3. Feminization (Empowerment of Women): Pinker uses “feminization” to denote the increasing influence of women in social, political, and cultural life . This is based on the observation that men commit an overwhelming proportion of violent acts, from individual assaults to starting wars, whereas women are statistically far less likely to resort to violence to resolve conflicts. As women gain power – through movements for women’s rights, greater representation in governance, and shifts in gender norms – societies often experience a tilt toward less violent values. One reason is that women, as primary caregivers of children and traditionally excluded from the warrior role, have had a vested interest in safety and stability. When women have more say (in the family or in national politics), issues like domestic violence, child welfare, and social spending on health and education tend to receive more attention, whereas aggressive posturing and militarism receive more skepticism. A striking historical example is the decline of foot-binding and female infanticide in China, which correlated with the influence of reformers (many inspired by Western women’s rights ideas) in the early 20th century – a case of society becoming less violent and cruel to women once women’s status slightly improved. In modern democracies, the rise of women leaders and voters has often coincided with more peaceful policies: some studies suggest that states with higher female political participation are less likely to initiate violence and civil conflicts. Feminization also works at the cultural level – qualities stereotypically labeled as “feminine,” such as empathy, compassion, and pacifism, become more culturally prominent and respected. For instance, compare the early 20th-century glorification of battlefield heroics (a very masculine ideal) to the early 21st-century emphasis on caregiving heroes (healthcare workers, teachers, etc.). Pinker is careful to note this is not about absolute differences or moral superiority of women, but statistical tendencies: as societies incorporate the voices and talents of the half of humanity that was traditionally sidelined from power, their politics and values often shift in a less violently competitive direction . A poignant illustration is the global movement against domestic violence: largely driven by women’s advocacy, it reframed wife-beating from a private matter to a public crime, leading to legal reforms and a significant drop in intimate partner violence over time. In summary, “feminization” as a force means that the empowerment of women – through education, rights, and leadership – has contributed to kinder, gentler norms and policies, damping the flames of our more violent male-centric demons like dominance and revenge, and bolstering better angels like empathy and moral care.

4. Cosmopolitanism (Expanding Circles of Sympathy): The term cosmopolitanism in Pinker’s framework refers to the broad set of historical developments that have exposed people to wider circles of knowledge, empathy, and social connection . This includes the spread of literacy, education, mobility, mass media, and the mixing of cultures – essentially anything that causes people to experience the world beyond their parochial insular group. When individuals become cosmopolitan, they often discover that those who seemed “other” are in fact fellow humans with whom one can identify. Pinker argues that cosmopolitanism – through literature, journalism, travel, urbanization – has “heightened people’s awareness of others different from themselves, attuning them to others’ suffering and fostering empathy.” . A clear example is the impact of literature: in the 18th century, novels (such as Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa) invited readers to empathize deeply with characters from different walks of life, arguably expanding the reader’s moral imagination. Historian Lynn Hunt has proposed that the epistolary novel helped people develop a sense of privacy and respect for individuals – possibly aiding movements like the campaign for human rights. In the 19th and 20th centuries, newspapers and later radio/TV brought distant atrocities or injustices to ordinary people’s attention, sparking humanitarian movements. One might recall how the televised images of starving children in Ethiopia (1980s) led to the Live Aid concerts and a surge in global charity, or how seeing the civil rights protestors brutalized by police on TV helped turn American public opinion against segregation in the 1960s. These are cases where media made faraway suffering personal and unignorable. Urbanization is another aspect: as people move to cities, they encounter neighbors of different backgrounds and must find ways to get along, breaking down village prejudices. International travel and exchange programs similarly broaden minds. Essentially, cosmopolitanism chips away at the demon of ideology when that ideology is based on demonizing an out-group; it’s harder to maintain that “our nation/religion is superior and others are subhuman” if you’ve befriended foreigners or consumed foreign art and ideas. It also reinforces the angel of empathy by continually reminding us that others have stories and feelings like our own. Pinker credits cosmopolitan forces – from the Enlightenment Republic of Letters to today’s Internet – with helping people “opt out” of reflexive tribalism and consider a more universal perspective. This has concrete effects: international cooperation efforts (like the Red Cross, United Nations, NGOs) are built on the notion that we should care about strangers. Even the fact that war and genocide are now globally decried owes something to cosmopolitan ethics – it’s no longer possible for a regime to commit mass violence without worldwide scrutiny and criticism, because global media and institutions shine a light. In short, cosmopolitanism has been a peace-promoting force by making the human family seem like a single community rather than warring tribes, thus mobilizing our better angels across boundaries that once divided us.

5. The Escalator of Reason (Rising Rationality): Finally, Pinker points to the “Escalator of Reason,” meaning the increasing application of knowledge and rational analysis to human affairs over the last centuries . This is closely tied to the Enlightenment and the scientific revolution. As scientific thinking and education spread, people became more adept at critical thinking – questioning superstitions, recognizing their own biases, and seeking evidence over tradition or authority. How does this reduce violence? In several ways. First, reason helps people to recognize the futility or counter-productivity of violence. For example, through rational inquiry we figured out that witches aren’t real – so burning innocent women as witches was clearly a horrific mistake, and that practice ended. Reason also allows for problem-solving through understanding: instead of seeing disease as a curse requiring a scapegoat, we learned to find medical solutions; instead of seeing crime as the work of “evil” people who must be brutally punished, criminology offers insights into social prevention strategies. Essentially, reason can replace a violent approach with a pragmatic, peaceful approach. Moreover, reason undergirds secular humanism, a worldview that bases ethics on logic and human welfare rather than dogma – this has led to more consistent anti-violence principles (e.g. if one values human well-being logically, one finds it hard to justify practices like torture or war except in extreme self-defense). The growth of international law and organizations mentioned earlier is also a triumph of reason: agreements like the Geneva Conventions or nuclear arms treaties are products of negotiation and evidence-weighing that reflect “cooler heads” prevailing. Pinker suggests that over time, rational discourse has debunked many violent ideologies. For instance, the concept of racial equality gained ground in the 20th century partly because scientific knowledge showed no fundamental biological difference justifying racism, and logical consistency (often highlighted by activists) made it untenable to claim rights for oneself while denying them to others. Likewise, the absurdity of endless cycles of violence can be illuminated by logical argument – many peace activists have been rationalists pointing out that violence usually fails to achieve its purported ends. The phrase “escalator” implies an upward trend: each generation, more humans are educated in logical and critical thinking, making them less susceptible to fanatical passions or gross errors that lead to violence. Importantly, reason often works in concert with empathy and moral sense: it can provide the facts and structure to our compassionate impulses, turning them into effective policies. For example, empathy might make us want to reduce suffering, moral sense tells us it’s right to do so, and reason figures out how (through say public health measures or conflict mediation techniques). All told, the escalator of reason has lifted the general intellectual climate so that rational debate, scientific understanding, and logical consistency have more influence on our decisions, and raw violence correspondingly less. This is not to say humans are perfectly rational now – but even a moderate increase in rational thinking (e.g. relying on data about crime to craft policy, rather than gut fear) can yield markedly less violent outcomes.

Interactions Among Trends, Demons, Angels, and Forces

The decline of violence, as Pinker presents it, is not the result of any single factor but rather a dynamic interaction of all the trends, demons, angels, and forces described above. Human society is complex, and these elements have sometimes clashed and sometimes reinforced each other in bringing out humanity’s “better nature.” This concluding section explores how these pieces fit together to produce the overall trajectory toward greater peace, cooperation, and respect for life.

One way to think of it is: historical forces shape the environment in which our inner demons or better angels gain the upper hand, leading to the observable trends of declining violence. For example, the rise of the Leviathan (a historical force) directly constrains certain inner demons like revenge and dominance by enforcing law and order . When a strong state imposes justice, people no longer need to seek vigilante revenge (dampening the revenge instinct) and would-be dominators are kept in check by superior force. In effect, the Leviathan force gives our better angel of self-control a boost – citizens learn to restrain their impulses because the state will punish outbursts, and over time this becomes internalized as a cultural norm. This dynamic played out during the Pacification Process and Civilizing Process: as governments expanded, violence subsided, illustrating a force (state authority) reinforcing an angel (self-control) to suppress demons (revenge feuds, dominance fights) .

Similarly, commerce and cosmopolitanism forces work hand-in-hand to elevate certain better angels like empathy and reason, while undercutting demons like predation and ideology. Commerce encourages people to use rational negotiation rather than force – a merchant calculates profit margins instead of plotting raids. Over time, societies steeped in commerce come to see violence as an irrational breakdown of business. This economic rationality aligns with the angel of reason, fostering a mentality that conflicts should be resolved through contracts and dialogue, not duels or wars. Meanwhile, trade and travel (as parts of commerce and cosmopolitanism) expose individuals to other cultures, humanizing former strangers. This clearly boosts empathy and broadens the moral sense (one starts to care about what happens to people in distant countries if they are one’s customers, colleagues, or friends) . These more empathetic attitudes then feed into movements like the Humanitarian Revolution and Rights Revolutions – which themselves are trends powered by the interaction of angels and forces. For instance, the abolition of slavery (a humanitarian reform) succeeded in part because economic changes (industrialization made slave labor less crucial) coincided with moral changes (religious and philosophical movements preaching the brotherhood of man). In Pinker’s terms, commerce (force) gave societies more to gain from peace, while cosmopolitanism (force) made them care more about peaceful values, causing the better angels to “gang up” on the demons of dominance and ideology that had sustained slavery .

The escalator of reason can be seen as a meta-force that strengthens all the better angels and helps design strategies to cage the inner demons. Reason in the Enlightenment led to new political ideas (democracy, separation of powers) that in effect caged the demon of dominance – no more divine right of kings to make war at a whim, but rather elected parliaments that debate and often veto wars. Reason also exposed the self-defeating nature of violent customs, as noted earlier, which in combination with empathy helped delegitimize practices from witch-hunts to torture. There have been instances where reason and empathy together directly confronted an inner demon: consider ideology-driven violence like religious persecution – the cosmopolitan and rationalist trends of the Enlightenment challenged it by arguing for freedom of conscience (a reasonable policy) and by encouraging people to see those of other faiths as fellow humans (an empathetic stance). Over time, this interplay diminished the role of violent religious intolerance in many societies. Pinker explicitly notes that the five historical forces have, over time, caused our inner demons to be overpowered by our better angels . The “overpowering” is rarely instantaneous or complete, but it’s cumulative. Each progressive change (trend) made it slightly harder for our demons to run rampant and slightly easier for our angels to prevail, creating a feedback loop favoring peace.

There are also clashes and trade-offs among these factors. Sometimes one better angel can conflict with another, or one historical force might aggravate an inner demon in the short run even as it reduces violence in the long run. For example, Pinker warns that the moral sense is double-edged – a strong moral ideology could inflame violence (as with revolutionary or religious zealotry). In history, we see that the early Rights Revolutions (like abolitionism) sometimes provoked violent backlashes driven by ideology or dominance (e.g. the U.S. Civil War was, in one light, a violent clash catalyzed by the moral movement to end slavery). Yet, that war ultimately quashed an even greater structural violence (the institution of slavery itself) and paved the way for further rights. This illustrates that progress can involve conflict: inner demons are not vanquished without a fight, sometimes literal. Another example is the 1960s spike in violence in Western countries . During that decade, an upsurge of liberalization and challenges to authority (arguably driven by empathy and a quest for freedom) inadvertently loosened social constraints too quickly, possibly allowing a temporary resurgence of violent crime. Pinker notes that the 1960s defied expectations – as prosperity and progress increased, violence unexpectedly ticked up . This reminds us that the balance between forces and impulses is delicate: a decline in the Leviathan’s influence (e.g. more lax policing or social discipline in the 1960s) might let dominance or predatory crime creep up. However, societies adapted – by the 1990s, crime was falling again as new equilibrium were found (better policing strategies, a cultural swing back to valuing order). The long-term trend resumed downward. Such episodes show the push-and-pull nature of these dynamics: when violence rises, societies often respond by reasserting the forces or norms that suppress it (e.g. after a crime wave, citizens support smarter law enforcement and community programs, reining in the demons anew).

Throughout history, the interaction is often synergistic: multiple forces combine to achieve a result that no single factor could. The abolition of judicial torture in Europe, for instance, required empathy (people began to feel the pain of the tortured as unacceptable), reason (Enlightenment critiques calling it ineffective and barbaric), and Leviathan (states had to have sufficient control to implement less brutal justice and still keep order). In earlier, less governed times, torture was partly used because it was thought to be the only way to control crime or heresy; once states grew more powerful and reason offered better methods (like modern policing and interrogation techniques), that particular violence could be retired. Likewise, the Long Peace after WWII can be credited to a combination of Leviathan (U.S. and Soviet superpower deterrence and later international institutions), commerce (the Marshall Plan tying economies together), cosmopolitanism (war-weary populations embracing peace movements and cultural exchange), and reason (realpolitik strategy to avoid nuclear holocaust). Meanwhile, better angels among leaders (e.g. cautious self-control by Kennedy and Khrushchev during the Cuban Missile Crisis) managed to suppress demons like dominance or ideological fervor at key moments. In contrast, when those elements fail to align – as in the breakdown of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, where a weakening Leviathan (the collapsing state) unleashed dormant ethnic ideologies and revenge impulses – violence can explode. But the broader pattern has been that, more often than not, forces of peace coalition together, creating conditions that favor de-escalation.

Importantly, Pinker’s thesis doesn’t claim our inner demons are gone or that violence is impossible now. It claims that on average, the positive forces and angels have been outcompeting the demons more and more. Humanity still wrestles with its violent inclinations, but we’ve built systems and cultures that tilt the scales toward peace. Consider the realm of international relations: the demon of dominance is still present (great powers jostle for influence), yet the creation of the United Nations, international law, and global trade networks serves as a modern Leviathan-commerce-cosmopolitan complex to manage that rivalry without world war. Or consider personal violence: the demons of predation or sadism still give us crime, but far less than before because policing, social safety nets, and shifting norms protect most communities. The better angels of empathy and moral concern mean that even when violence does occur, we react with horror and seek justice, rather than shrugging it off as normal. Indeed, as Pinker notes, our standards have risen – today, even a single hate crime or a lone terrorist attack is seen as a grave social failing, whereas centuries ago large-scale atrocities could be routine and accepted . This change in attitude itself is a result of the interactions of all the factors: we expect people to control themselves (self-control), to care about others (empathy, moral sense), and we have built societies that on the whole reinforce those expectations with laws and education (Leviathan, reason).

In philosophical terms, one could say the narrative of declining violence is a story of human progress through Enlightenment – not just the 18th-century movement, but the general enlightenment of our species about how to live together. It is the gradual enlightenment that might is not right, that individuals have inherent worth, and that rational cooperation beats plunder and revenge. Each historical trend – from the Pacification Process to the Rights Revolutions – was a chapter in this story, propelled by the five forces. And each chapter saw a struggle between our dark and better selves, with the scales increasingly tipping toward the better angels. The end result, as Pinker daringly asserts, is that we live (as of the early 21st century) in the most peaceable era of our species’ existence . This does not mean a perfect era, but comparatively, an age where violence is at a historic low and widely regarded as unacceptable.

To conclude, the decline in violence has been a multi-dimensional victory. It required taming our inner demons (through deterrence, education, and norm changes) and empowering our better angels (through empathy-building, moral evolution, and rational institutions). The six historical trends chart the milestones of that victory – from the first kings who quelled tribal feuds, to the modern movements that champion the rights of every human (and animal) not to be harmed. The five historical forces were the engines driving those milestones – the state, trade, feminism, cultural exchange, and reason all pressed the balance toward peace. And woven through it all is an interplay: sometimes tense (when demons exploit a lapse in forces) but overall reinforcing. The demons and angels duel within each of us, but thanks to the structures and ideas our civilizations have developed, the angels have gained an upper hand. This dynamic interplay of forces, motives, and events has brought out humanity’s better nature, showing that even if perfect peace remains a goal, a significant improvement in peace and cooperation is an accomplished reality . Understanding this interplay not only explains our past but also offers hope – and guidance – for continuing the trajectory toward a more harmonious and nonviolent world