From Stone to Silicon

Human behavior is the result of a deeply interwoven fabric of genetic predispositions, cultural conditioning, and evolutionary pressures—all of which have been continuously interacting for hundreds of thousands of years. To understand how these forces shape our conduct, decisions, and social structures, it is necessary to look at both the long arc of human evolution and the rapid transformations brought about by cultural development.

⸻

1. The Genetic Foundations of Behavior

From the standpoint of biology, human behavior is not arbitrary; it is influenced by inherited genetic tendencies that evolved to solve survival and reproductive challenges faced by our ancestors. These predispositions include:

- Social bonding and cooperation — Early humans who formed alliances, shared resources, and cared for offspring collectively had greater survival chances. This fostered the genetic basis for empathy, altruism, and group loyalty.

- Fight-or-flight responses — Instinctive reactions to threats are rooted in neural circuitry shaped during the Pleistocene, when predators, hostile tribes, and environmental hazards were constant.

- Mate selection preferences — Certain patterns in attraction—such as signals of health, fertility, or resource acquisition—are partly rooted in evolutionary reproductive strategies.

- Cognitive biases — Many mental shortcuts, such as loss aversion or preference for immediate rewards, are likely evolutionary relics from environments where scarcity and unpredictability were the norm.

In short, the biological architecture of the human brain—our neurotransmitters, emotional regulation systems, and learning capacities—evolved under selective pressures that rewarded survival in small, kin-based groups.

⸻

2. The Cultural Layer: A Rapid Evolutionary Force

While genes change slowly, culture can transform almost overnight. Cultural evolution—the spread, modification, and transmission of ideas, norms, and practices—can modify or even override certain genetic tendencies. Key mechanisms include:

- Language — Perhaps the most powerful cultural tool, language allows the transmission of knowledge, myths, moral codes, and scientific understanding far beyond the limits of genetic inheritance.

- Social norms and laws — Culture defines acceptable behavior, sometimes counteracting natural instincts (e.g., outlawing violence, promoting monogamy, encouraging altruism toward strangers).

- Technological advancements — From the domestication of plants and animals to the internet, technology reshapes how humans live, work, and relate.

- Memetics and symbolic systems — Cultural “units” of information—religion, ideology, artistic styles—spread rapidly and shape perception and decision-making.

Whereas genetic evolution operates over thousands of generations, cultural change can occur within a single lifetime, producing a dynamic tension between ancient instincts and modern social expectations.

⸻

3. The Co-Evolution of Genes and Culture

Genetic and cultural factors are not independent—they interact in a process called gene–culture coevolution. Some examples:

- Lactose tolerance evolved in populations with a cultural tradition of dairy farming.

- Disease resistance increased in regions with dense agricultural settlements where pathogens spread more easily.

- Psychological traits—such as risk-taking, conformity, or openness to new experiences—may have been selected for or against depending on the cultural context.

This interplay means that human nature is neither fixed solely by biology nor entirely a product of social conditioning; instead, it is a moving target shaped by both domains.

⸻

4. The Role of Evolution in Modern Society

In the modern era, biological evolution continues, but cultural evolution has outpaced genetic change by orders of magnitude. This creates certain paradoxes:

- Mismatch between ancient instincts and modern environments — We are adapted for scarcity, yet live amid abundance, contributing to issues like obesity, addiction, and chronic stress.

- Social and technological acceleration — Our brains evolved for face-to-face interaction in small groups, yet we now navigate vast, anonymous digital networks.

- Ethical dilemmas of biotechnology — Advances in genetic engineering, AI, and reproductive technology challenge traditional evolutionary processes, allowing deliberate modification of traits.

Despite these mismatches, evolutionary psychology helps explain modern behavior—from voting patterns to consumer choices—by recognizing that the same neural architecture that guided hunter-gatherers still underlies decision-making today.

⸻

5. The Future: Evolution by Choice?

In the coming centuries, natural selection may be overshadowed by artificial selection and self-directed evolution. Humans are already altering the evolutionary trajectory through:

- Medical interventions that allow survival of traits once disadvantageous.

- Gene editing (CRISPR and beyond) that may deliberately alter cognitive, physical, or emotional capacities.

- Cultural pressures that redefine what is valued, desired, or rewarded in a population.

If the past was shaped by the slow grinding of natural selection, the future may be shaped by conscious design—raising profound ethical and philosophical questions about what it means to be human.

⸻

Takeaways

Human behavior is a product of deep biological roots intertwined with a fast-changing cultural canopy. Evolution provides the foundation—the universal capacities, biases, and drives that made our species successful. Culture paints the surface, rapidly shifting the patterns of behavior, morality, and identity. In modern society, these forces sometimes harmonize and sometimes conflict, and understanding their interplay is essential for navigating the challenges of globalization, technology, and ethical self-determination.

⸻

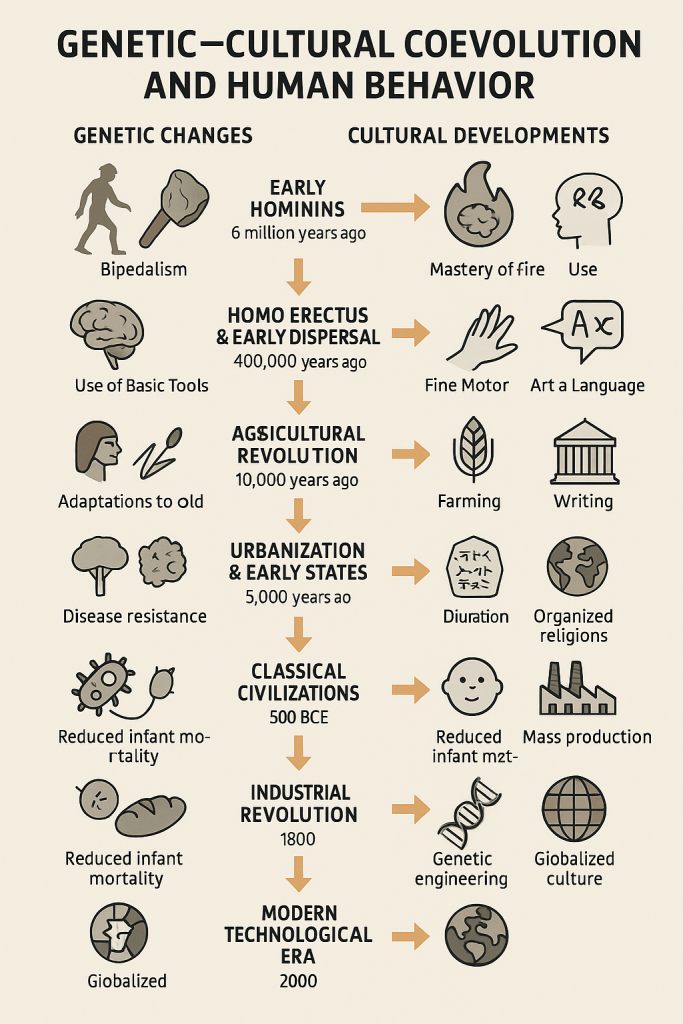

Here’s a chronological map showing how genetic and cultural factors have co-shaped human behavior, with emphasis on key turning points where biology and culture intertwined.

Timeline of Genetic–Cultural Coevolution and Human Behavior

| Era / Period | Approx. Date | Key Genetic Changes | Key Cultural Developments | Impact on Human Behavior |

| Early Hominins | 6–2 million years ago | Bipedalism; changes in pelvis and spine; hand dexterity from thumb evolution | Use of basic stone tools | Freed hands for tool use, cooperative foraging, and carrying; small-group cooperation essential for survival |

| Homo erectus & Early Dispersal | 2 million – 400,000 years ago | Larger brain volume (~900 cc → 1,200 cc); refined hand motor control | Mastery of fire; more complex tool-making (Acheulean handaxes) | Fire enabled cooking (improved digestion, calorie yield); social gatherings around hearths reinforced cooperation and language precursors |

| Neanderthals & Archaic Humans | 400,000 – 50,000 years ago | Enhanced musculature; adaptations to cold climates; FOXP2 gene variants linked to speech | Burial practices; pigment use; regional tool styles | Emergence of symbolic behavior, proto-language, and cultural identity markers |

| Cognitive Revolution (Homo sapiens) | ~70,000 years ago | Fine motor control, brain lateralization; possible selection for symbolic thought and storytelling | Explosion of art, language, myths; long-distance trade | Abstract thinking allowed planning, complex social hierarchies, and rapid cultural innovation |

| Agricultural Revolution | ~10,000 years ago | Lactase persistence in pastoralist groups; increased disease resistance in dense populations | Farming, permanent settlements, domestication of plants and animals | Shift from nomadic to sedentary life; property concepts, organized religion, and social stratification emerge |

| Urbanization & Early States | ~5,000 years ago | Adaptations to high-carb diets; gene–culture effects on social stress resilience | Writing systems; codified laws; complex trade networks | Large-scale cooperation beyond kinship; legal and moral systems begin to override some instinctual behaviors |

| Classical Civilizations | 2,500–1,500 years ago | Potential selection for literacy-related cognitive traits in some populations | Philosophical schools, organized religions, imperial administration | Expansion of moral codes, long-term planning, and abstract governance systems |

| Medieval to Early Modern Era | 500–1700 CE | Immunity adaptations to diseases like plague, smallpox | Printing press; navigational technology; global trade | Accelerated spread of ideas; cultural exchange intensifies; economic systems shift |

| Industrial Revolution | 1750–1900 CE | Gradual height and health improvements from better nutrition; selection shifts due to reduced infant mortality | Mass production, public education, urbanization | Work patterns, family structures, and gender roles transform; rise of wage labor and global economy |

| 20th Century Technological Acceleration | 1900–2000 CE | Reduced selection pressure due to medicine; gene–culture lag appears (ancient instincts in modern environments) | Mass media, internet, globalization | Instant communication reshapes relationships, politics, and identity; cultural norms change rapidly |

| 21st Century & Beyond | 2000–Present | Emergence of direct genetic engineering (CRISPR); artificial reproductive technologies | AI, biotechnology, globalized cultural memes | Potential shift from natural to artificial selection; ethical debates about human enhancement and identity |

⸻

Key Insights from the Timeline

1. Slow Genes, Fast Culture — Biological evolution operates over tens of thousands of years, while culture can transform human behavior within a generation.

2. Feedback Loops — Cultural innovations (e.g., dairying) created environments that favored certain genetic mutations (lactase persistence).

3. Mismatch Phenomena — Many modern health and social issues (e.g., obesity, anxiety, political polarization) stem from ancient instincts colliding with new cultural realities.

4. Future Direction — We are entering an era where humans may consciously alter their own evolutionary trajectory, blending genetics, technology, and culture in unprecedented ways.