The Supermarket Standstill

It’s 8:17 PM on a Tuesday, and I’m standing in the dairy aisle of a brightly lit supermarket, paralyzed before 47 varieties of milk. Skim, 1%, 2%, whole, lactose-free, almond, oat, soy, pea, macadamia, organic, ultra-pasteurized, grass-fed, vitamin-enriched. My hand hovers, then retreats. Fifteen years ago, this same decision took approximately three seconds. Today, it consumes five minutes of increasingly anxious calculation as I weigh nutritional content, ethical production, environmental impact, and the terrifying possibility of choosing wrong.

This everyday paralysis is where modern freedom goes to die—not with a bang, but with a whimper in the dairy section. We live in the Age of Choice, where the ability to select from a menu of options has become synonymous with freedom itself. As historian Sophia Rosenfeld reveals in The Age of Choice, this connection is neither ancient nor natural, but a modern invention carefully constructed over centuries . We’ve been sold a story that more choice equals more freedom, yet the reality is that this very equation often leaves us overwhelmed, anxious, and less free—all while obscuring the hidden architectures that control our choices in the first place.

The Invention of Choice: How Freedom Got Redefined

The Historical Construction of Choice-as-Freedom

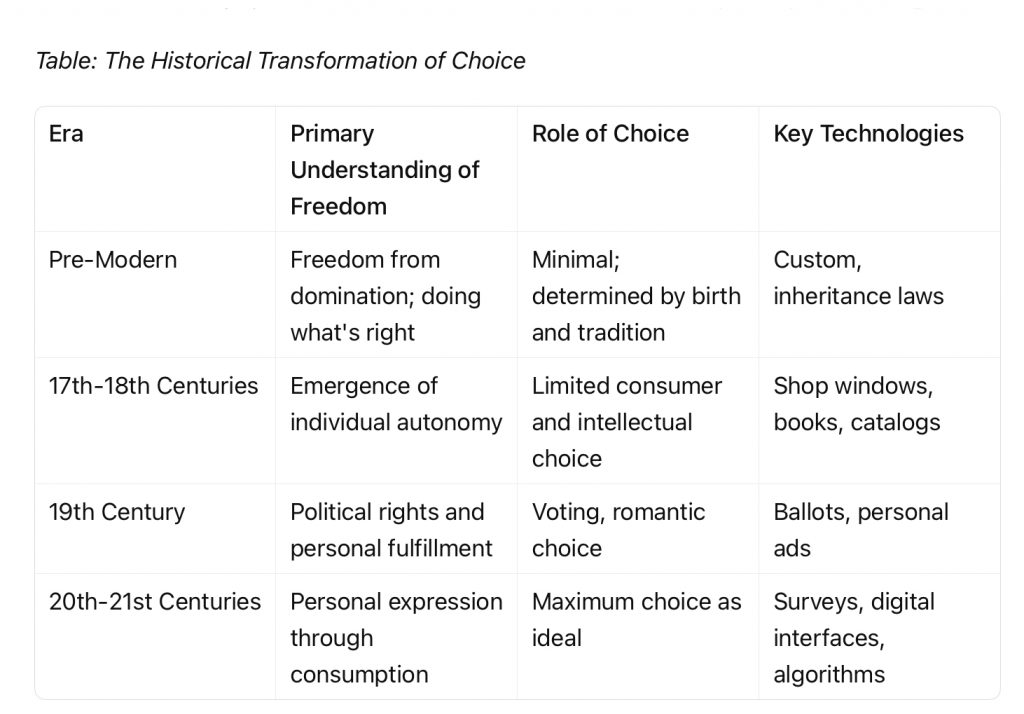

For most of human history, freedom had little to do with personal choice. As Rosenfeld’s research illustrates, prior to the 17th century, being truly free often meant not having to make trivial choices at all—your path in life was largely determined by birth, tradition, and social station . Freedom was conceived as living without domination or doing what was morally right, not selecting from a menu of possibilities.

What transformed this understanding?

The five key developments that gradually rebuilt freedom around individual choice:

· Markets and Shopping: The emergence of consumer culture in the 17th and 18th centuries allowed ordinary people to select goods based on personal preference rather than tradition. Shop windows, catalogs, and later, department stores turned choice into a visible symbol of individuality .

· Belief and Ideas: The Enlightenment promoted the radical notion that people should “think for themselves,” choosing their own beliefs rather than accepting religious or political authority. This intellectual choice, however, remained contingent on education and privilege .

· Love and Personal Life: The shift from arranged marriages to partnerships based on romantic choice represented a monumental change in how people conceived of personal autonomy, even as social constraints continued to limit these choices .

· Politics and Voting: Modern democracy made political choice through secret ballots and elections the ultimate expression of freedom, though this was always structured by citizenship rules and political machinery .

· Science of Decision-Making: By the 20th century, entire disciplines like psychology and economics emerged to study how people choose, transforming “free choice” into both a subject of study and a tool for social engineering .

What’s crucial to understand is that this development required new technologies and rules to function—ballots, catalogs, surveys, and later digital interfaces—all of which made choice-making manageable while inevitably constraining it . The “free market” itself only works through extensive regulation and what behavioral economists call “choice architecture”—largely invisible rules about who can choose what, when, and how .

The Hidden Mechanisms: How Our Choices Are Being Steered

The Neuroscience and Psychology of Choice

Modern science has revealed just how malleable our decision-making processes are—knowledge that’s being systematically exploited. Neuroscientists have identified that when we make simple choices, our brains compute a value signal—essentially calculating expected benefit based on previous experience . This process occurs primarily in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, with dopamine neurons in the ventral striatum helping update values when experiences don’t match expectations .

The Attentional Drift Diffusion Model (aDDM) reveals how susceptible this process is to manipulation. Studies show that when choosing between two items we like equally, we’re significantly more likely to choose whatever we look at last before deciding . Simply controlling how long we view an option can increase our likelihood of choosing it by 6-11% . In supermarket environments, this translates to grabbing what’s directly in front of us, especially when cognitive load is high .

Marketing now leverages these insights with frightening precision. Through eye-tracking, mouse movement analysis, and neuroimaging, companies can measure affective responses and attentional patterns to optimize how they present choices . The result? What feels like free choice is often a carefully engineered outcome.

The Paradox of Choice: Overload Versus Deprivation

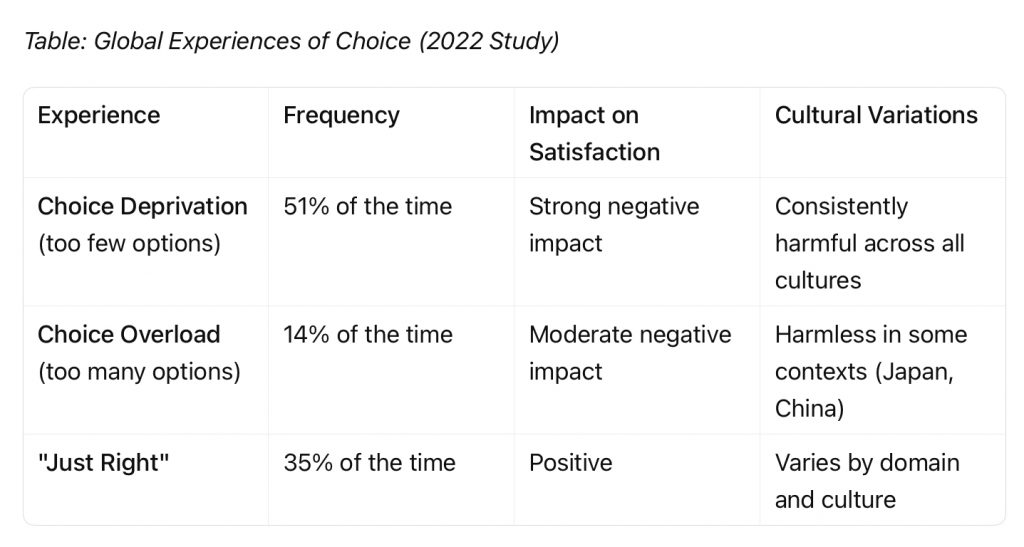

Barry Schwartz’s “paradox of choice” theory—that too many options paralyze us—has become conventional wisdom. But newer research reveals a more complex picture. A massive 2022 study across six countries with over 7,400 participants found that choice deprivation—feeling you have too few options—is actually more common and often more harmful than overload .

Globally, participants reported having too few options 51% of the time, compared to too many only 14% of the time . The negative impact of deprivation was typically stronger—having too few doctors to choose from made Americans six times less satisfied than having too many . These findings varied cross-culturally, with choice overload being rare and sometimes harmless in countries like Japan, China, India, and Russia .

Table: Global Experiences of Choice (2022 Study)

Experience Frequency Impact on Satisfaction Cultural Variations

Choice Deprivation (too few options) 51% of the time Strong negative impact Consistently harmful across all cultures

Choice Overload (too many options) 14% of the time Moderate negative impact Harmless in some contexts (Japan, China)

“Just Right” 35% of the time Positive Varies by domain and culture

Businesses have taken note of this psychology. The most effective sales strategies now present three pricing options (with customers gravitating toward the middle), create clear categories to navigate abundance, and provide default choices to minimize decision fatigue . Even email marketing timing is optimized for when we have the most mental energy—around 7 AM or 11 AM local time .

The Democratic Dilemma: Choice as Political Theater

The connection between choice and freedom becomes particularly fraught in politics. As Rosenfeld notes, democratic systems are built on the notion that the governed should have choice in who governs them . Yet this ideal often clashes with reality.

Former Thai Prime Minister Anand Panyarachun observed that while free markets theoretically enable wide latitude of choice in economic life, they don’t necessarily lead to democratic government . Many authoritarian countries allow free markets to exist, disproving the simplistic notion that capitalism naturally begets democracy .

The deeper problem may be what Panyarachun calls the “intervention of the market mechanism in our system of government” —when political choices become subject to the same manipulation as consumer choices. When politicians can be “sold” like products, using the same attention-grabbing techniques and simplified messaging, the democratic ideal of informed choice gives way to engineered outcomes.

Beyond the Individual: The Social Costs of Choice Mythology

Perhaps Rosenfeld’s most crucial insight is how our obsession with individual choice undermines collective action and obscures structural inequalities . When we frame freedom entirely around personal choice, we naturally begin to blame individuals for “bad choices” while ignoring how their options were constrained from the start.

This mindset has devastating social consequences:

· Erosion of Collective Responsibility: Focusing exclusively on individual choice draws attention away from shared goals like combating climate change, where collective action rather than consumer choice is needed .

· Blaming the Disadvantaged: Poor choices are often attributed to personal failings rather than recognizing how poverty itself limits options .

· Commodification of Everything: When choice becomes the ultimate value, everything—including education, healthcare, and relationships—gets framed as a consumer decision.

The wellness industry exemplifies this problem, often using the language of science to market products with little actual evidence . Advertisers borrow scientific imagery—lab coats, DNA strands, graphs—to create “an aura of credibility” without presenting genuine data . They leverage the gap between technical meanings and consumer interpretations, using phrases like “clinically proven” or “doctor recommended” that sound substantive but are legally flexible .

The Way Forward: Freedom Beyond the Menu

So what might a healthier relationship with choice look like? Rosenfeld isn’t arguing for eliminating choice, but for being more discerning about when it truly serves freedom and when it doesn’t . This means:

· Recognizing Meaningful Versus Trivial Choice: We might want fewer, better-quality options in healthcare rather than the anxiety of choosing between nine confusing insurance plans .

· Removing Harmful Options: Some choices—like purchasing military-grade weapons—shouldn’t be available at all .

· Balancing Individual and Collective Good: Sometimes limiting some people’s choices can expand others’, creating greater overall freedom .

· Developing Choice Literacy: Understanding how our choices are manipulated—through attention steering, option framing, and emotional triggers—is the first step toward genuine autonomy.

The next frontier in this struggle involves artificial intelligence, which promises to further expand and tailor our choices while potentially constraining which options we ever see . As algorithms become sophisticated choice architects, understanding the history and psychology of choice becomes not just academically interesting but essential for preserving meaningful freedom.

Takeaways: Choosing What Matters

I finally grab the oat milk—a choice determined by some combination of environmental concern, the attractive packaging at eye level, and decision fatigue. But Rosenfeld’s work leaves me with a more important question: What if real freedom isn’t about choosing between options someone else has designed for us, but about participating in designing the options themselves?

The true crisis of the Age of Choice may be that we’ve become so preoccupied with navigating menus that we’ve forgotten we could be writing them. Freedom might not be the endless selection of what’s available, but the ability to shape what should be available in the first place—to decide, collectively, what counts as a choice worth having.

Perhaps genuine liberation begins when we stop asking “Which of these should I choose?” and start asking “Who decided these were my options?”—and “What can we choose together that we cannot choose alone?” That’s the choice that really matters, and it’s one no one can make for us.