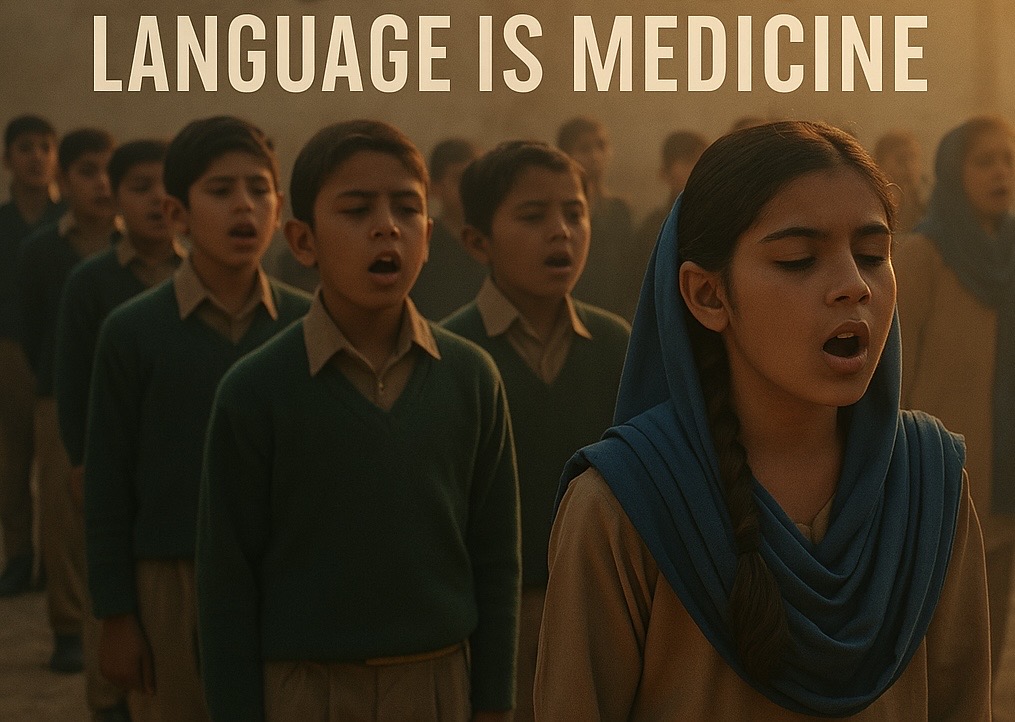

From the outside, the village school in central Punjab looks like any other in Pakistan’s heartland. Children stream in carrying satchels and cricket bats, boys in neatly ironed shalwar-kameez, girls in blue dupattas. Morning assembly begins with recitation, but the language that fills the dusty courtyard is not the one most of their parents speak at home. In Punjab – a province of over 127 million people , more than half the country’s population – the majority of government schools still teach children to read, write and think in Urdu or English rather than in Punjabi. That is unusual. UNESCO notes that educating children in their mother tongue is a key factor for inclusion and quality learning; it improves learning outcomes, increases the speed of comprehension and empowers students to take part in society . Yet in Punjab, the language of the marketplace and the wedding song has been kept out of the classroom.

Any storyteller from this region knows that this tension goes back generations. Colonial administrators in British India deliberately promoted Urdu over Punjabi in the Punjab province, partly to create a loyal intermediary class and to weaken the communal bonds that resistance movements drew upon. After partition, Pakistan embraced Urdu as a unifying national language. In theory, adopting a lingua franca would bind diverse peoples together; in practice it often rendered the majority tongue invisible. When you strip a population of its mother tongue in public life, you do more than reallocate classroom hours. You send a message that their stories, idioms and ways of knowing are unfit for the modern world. This is not a neutral policy: during centuries of colonisation, languages were “actively minoritised, marginalised and pushed out to the fringes” . Punjabi has survived in homes and marketplaces, in Sufi poetry and qawwalis, but generations have internalised the idea that success requires leaving it behind.

The consequences go beyond vocabulary. There is mounting evidence that the vitality of a people’s language is tied to their health and wellbeing. A decade‑long study of the Alyawarr and Anmatyerr communities in Utopia, Australia – a remote region where 88 per cent of people speak their own language – found that hospitalisation and mortality from cardiovascular disease were dramatically lower than for other Aboriginal communities . The researchers attributed this advantage not to wealth or formal education but to connectedness to culture, family and land, and opportunities for self‑determination . In Canada’s British Columbia, communities where at least half the residents had conversational knowledge of their Indigenous language reported almost no youth suicides, whereas those with only minority language knowledge suffered suicide rates nearly six times higher . These findings suggest that language loss is more than a marker of social change; it can be a risk factor for disease in and of itself .

Could similar dynamics be at play in Punjab? Punjabi culture is rich in proverbs about health: “jithē bhāṇe nāl pyār, uthon āmrijhār” (where there is love, there is nectar). When children never read or write these words in school, they learn that their ancestral wisdom belongs only in the private sphere. They may grow up fluent in English grammar yet unable to write a letter to their grandmother. As in other colonised societies, this alienation from one’s linguistic roots can feed self‑doubt. The linguist Jaeci Hall described speaking her heritage language after years of suppression as an “endorphin rush” that helped heal wounds of colonisation . Conversely, Robert Elliott of the Northwest Indian Language Institute noted that “kids who don’t know who they are don’t understand their culture – they feel lost and are much more likely to fall prey to the type of problems that are plaguing a lot of Native communities” . Punjabi children who never see their language validated in school may internalise a similar sense of loss.

To be fair, proponents of Urdu- and English‑medium schooling raise practical arguments. Urdu is associated with national cohesion; English is seen as the language of global opportunity. Parents worry that an exclusively Punjabi‑medium education might limit their children’s prospects in higher education or the job market. These concerns have merit. No one is proposing that students learn only Punjabi to the exclusion of other languages. Multilingualism is an asset; indeed, UNESCO emphasises that mother‑tongue education lays the foundation on which additional languages can be more easily mastered . Research shows that literacy skills transfer from the first language to second and third languages, so teaching Punjabi in the early years would likely enhance, not hinder, proficiency in Urdu and English.

There are also internal complexities. Punjab is not monolithic: languages like Saraiki, Hindko and Pothohari claim their own literatures and identities. Elevating standard Punjabi alone could marginalise these voices. A truly inclusive language policy would need to recognise the province’s linguistic diversity, perhaps by allowing local mother tongues in early grades and introducing Punjabi, Urdu and English sequentially. Moreover, language alone cannot resolve the structural inequities – poverty, gender disparities, rural-urban divides – that shape health outcomes. The Aeon essay makes this clear: linguistic oppression interacts with housing, land rights and access to healthcare . Punjab’s villages suffer from poor sanitation, limited healthcare facilities and economic precarity. Empowering communities linguistically must go hand in hand with investments in infrastructure and services.

Nevertheless, the principle remains: people thrive when they can think, dream and learn in the language of their hearts. When a language disappears from public life, it takes with it an entire cultural and intellectual heritage . The story of Utopia shows that cultural continuity can protect against chronic disease . The story of British Columbia shows that language knowledge can save lives . Punjab’s story is still being written. In recent years there have been calls within the provincial assembly to introduce Punjabi as a subject and medium of instruction, and some private schools have begun experimenting with bilingual curricula. These efforts recognise that language revitalisation is not a nostalgic indulgence but a form of medicine – a way to mend the rift between self and society.

So imagine, in the not‑so‑distant future, a classroom in the same village school. The children stand for assembly and sing a folk song collected by Baba Bulleh Shah. They learn arithmetic in Urdu, conduct science experiments in English, and discuss Waris Shah’s Heer in Punjabi. When they go home, they do not switch codes because their learning is rooted in the language spoken at their kitchen tables. They are at ease in their own skin and equipped to engage with the wider world. That future is possible if policymakers heed the evidence that language is medicine, and if communities insist that healing begins by honouring the tongues we inherited.