Imagine an elderly man with Alzheimer’s disease who rarely speaks suddenly humming along to a familiar lullaby, his eyes lighting up with recognition. In another scene, a stadium full of strangers moves in unison, hearts pounding in time to a rock anthem as they dance and sing together. In a quiet classroom, children recite their ABCs effortlessly when the letters are set to a simple melody. These moments, diverse as they are, all reveal a common truth: music has a profound influence on the human brain. From rhythm and melody to harmony and frequency, music engages our minds and bodies in unique ways – lifting moods, triggering memories, aiding healing, and binding communities. Modern science is beginning to unravel how and why music has these powerful effects, offering insight into what happens in our brains when we feel the beat or get a song stuck in our head.

The Brain on Music: A Whole-Brain Experience

Music might enter through our ears, but it resonates through the entire brain. Neuroscientists have found that listening to music lights up multiple brain regions at once, making it akin to a full-body workout for the brain . When you play or hear a tune, the auditory cortex first processes the sounds and tones, while the motor cortex may start priming your muscles to tap your foot or dance . The prefrontal cortex springs into action as well – setting up expectations for patterns and rhythm – and the limbic system (including the amygdala and hippocampus) generates emotional reactions and links music to memories . In fact, nearly every major region has a role: the auditory cortex analyzes sounds, the visual cortex can be active if you’re reading music or watching performers, the sensory cortex gives feedback when you move to music, and the cerebellum helps coordinate timing and rhythm . Brain scans of people listening to music show many of these areas “lighting up” in synchrony, demonstrating that music isn’t just an auditory experience but a whole-brain phenomenon .

Critically, music engages the brain’s reward circuitry as well. Researchers have observed that when people hear music they love, an ancient deep-brain structure called the nucleus accumbens releases dopamine – the same neurotransmitter that gives us pleasurable feelings from food, sex, or other rewards . This dopamine rush contributes to the “chills” or euphoria we sometimes feel during our favorite songs. What’s remarkable is that the brain often starts anticipating the pleasure of a peak moment in a song before it even arrives: one study found that the caudate nucleus (involved in anticipation) becomes active as a highly anticipated musical climax nears, while the nucleus accumbens fires when the peak emotional moment actually hits . In essence, our brains are continuously predicting musical patterns and rewarding us when those expectations are met or artfully surprised – a neural dance of expectation and reward.

Rhythm: Syncing Brain and Body

One of music’s most elemental components is rhythm, the beat that can drive us to tap our feet or nod our heads without thinking. Even infants as young as a few months old will move in time with music, hinting that the connection between rhythmic sound and movement is deeply ingrained in the brain . In fact, our brains don’t just hear rhythm – they internalize it. Neuroscientists describe a phenomenon called neural entrainment, where the brain’s electrical oscillations synchronize with the tempo of music . In effect, external beats set our internal neural metronome. This can be seen with EEG scans: when you listen to a steady drumbeat, your brainwaves literally start to “dance” along in time . Our motor system is especially involved – the brain’s motor cortex and cerebellum coordinate with rhythmic inputs, which is why a strong beat often triggers unconscious movement . As one music therapist put it, “If I play a rhythm, I can affect the rest of the body. The body naturally aligns with a rhythm in the environment” . In other words, rhythm is a key way music bridges mind and body, compelling us to sway, clap, or dance.

This synchronization has powerful effects. Rhythmic music can drive physical coordination and has found therapeutic uses in conditions like Parkinson’s disease. Patients with Parkinson’s, who often struggle with movement and gait freezing, can walk more steadily when they step to a rhythmic pulse or metronome beat – their brains use the musical timing as an external scaffold to guide motion. In clinical rehabilitation, this is known as rhythmic auditory stimulation, and it can significantly improve walking speed and balance in Parkinson’s patients by essentially “re-timing” the brain’s motor signals with music. The same principle helps stroke survivors in regaining motor function: a stroke patient might practice moving an affected arm or leg in time with music, leveraging the brain’s tendency to entrain to rhythm to rebuild neural connections.

Rhythm also influences our physiology and mood through what might be called the body’s natural tempos. A fast-paced song (think of an upbeat dance track) can increase heart rate and breathing, energizing us, whereas a slow lullaby might do the opposite – calming the heart and inducing relaxation . Studies have noted that listening to fast-tempo music tends to raise pulse and blood pressure (likely via the adrenaline associated with excitement), while slow, gentle music can lower blood pressure and release tension . Our autonomic nervous system – which controls things like heart rate, breathing, and even hormone release – is sensitive to musical rhythm . For example, a soothing melody can decrease levels of the stress hormone cortisol and even increase oxytocin, a hormone associated with social bonding and relaxation . This is why slow classical music or calming sounds are often used for stress relief or in clinical settings to help patients relax: the slow rhythm entrains the body into a calmer state.

Not least, rhythm in music evokes that almost irresistible urge to move that we call groove. A strong groove can engage the brain’s reward system and motor areas together, giving us pleasure in movement. A recent neuroscience theory – Neural Resonance Theory (NRT) – suggests that this happens because the patterns of musical rhythm resonate with natural rhythmic firing patterns in our brain . According to NRT, we don’t just predict beats in a purely intellectual way; rather, our brain’s oscillations lock onto the beat, and this physical coupling is what makes us want to dance . In essence, the brain embraces rhythmic music by synchronizing with it, which explains why a catchy beat is so universally compelling. Indeed, researchers point out that the urge to move to music – to tap a foot or sway along – is a nearly universal human response . It’s no wonder that across cultures, drums and rhythmic chants have been used in ceremonies and celebrations for millennia; rhythm taps into a fundamental aspect of our biology, uniting groups in a shared temporal groove.

Melody and Harmony: Emotion and Mood

Listening to a favorite melody can spark joy, trigger chills, or move one to tears, underscoring music’s remarkable ability to stir our emotions. We’ve all experienced how a certain song can change how we feel: an uplifting melody might brighten our mood, while a melancholic tune can bring a lump to our throat. Melody and harmony – the sequences of notes and chords – interact with our brain’s emotional centers in complex ways. For one, music activates the same neurotransmitters and brain structures involved in other strong emotional pleasures. As mentioned earlier, enjoyable music triggers the release of dopamine in the reward circuit of the brain, particularly in the nucleus accumbens . In fact, scientists have shown that if dopamine signaling is chemically blocked, people’s ability to feel musical pleasure is dampened, whereas enhancing dopamine makes the emotional high from music even stronger . This is clear evidence that dopamine is causally involved in the chills and euphoria of music. Listening to the music you love literally causes your brain to flood itself with this “feel-good” chemical, underlining why a great song can make us feel on top of the world .

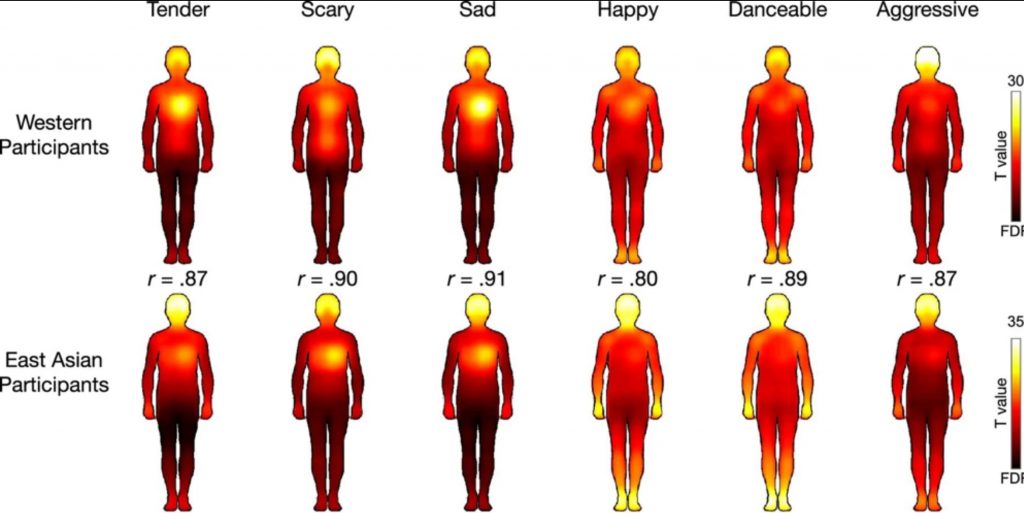

But music’s emotional power isn’t only about raw pleasure. Different combinations of notes and harmonies can convey or induce specific feelings. A gentle consonant harmony might sound tender or calming, while dissonant chords can create tension or anxiety. Our brains continuously interpret these musical features, often in ways that mirror vocal emotion; for example, a rising melody in a major key might evoke happiness or triumph (similar to an excited speaking tone), whereas a slow minor key melody can sound sorrowful or nostalgic. Interestingly, research indicates that these associations aren’t purely cultural – there are universal tendencies. Across cultures, fast tempos and consonant harmonies generally feel more positive or energizing, whereas very slow, dissonant music can feel sad or unsettling. One scientific study mapping where people feel music in their bodies found that “danceable” upbeat songs were felt as energizing sensations all over the body (especially in the limbs), while “sad” or “tender” songs were felt more in the chest and head, evoking a heavy heart or pensive mind . Notably, this pattern was consistent between Western and East Asian listeners, suggesting common biological emotional responses to certain musical qualities .

Beyond basic emotions, music is a tool for emotional regulation. Many people use music intuitively to manage their mood – perhaps you play calming music to soothe anxiety, or an aggressive song to vent anger, or an upbeat playlist to motivate yourself during exercise. The brain’s stress systems are directly influenced by music. Calming melodies can reduce cortisol (lowering stress) and even increase serotonin, leading to improved mood and relaxation, while exciting music can trigger adrenaline and boost alertness. Music can also reduce levels of physical pain by redirecting attention and prompting the release of endorphins (natural painkillers). For example, studies have shown that listening to music that gives you “chills” is associated with a higher pain tolerance, likely because the dopamine and endorphin rush from the music dampens pain signals . Hospitals have capitalized on this effect: patients who listen to soothing music before or after surgery often report less anxiety and require less pain medication, demonstrating music’s analgesic and anxiolytic benefits in a clinical context .

Crucially, music’s effect on emotion is tied to its ability to create expectations and resolution. Our brains are pattern-finding machines; when listening to a song, the brain continuously tries to predict the next note or chord based on experience. A skilled composer or songwriter plays with these expectations – sometimes fulfilling them (which can feel satisfying and resolving), and sometimes violating them (which creates tension or surprise). When a tense musical buildup finally resolves into a harmonious chord, listeners often feel a wave of relief or joy. This is partly neurological: the amygdala (the brain’s emotion hub) responds to unexpected shifts in music, and the medial prefrontal cortex helps assign personal value to the sounds . If the resolution is pleasing, the reward circuit kicks in with dopamine. Thus, melody and harmony engage an emotional push-and-pull in the brain – a dance of prediction, surprise, and fulfillment that can move us deeply. It’s a dynamic similar to what we experience in other emotional contexts (like a suspenseful story with a happy ending), but music expresses it abstractly through sound. That abstraction may be why musical emotions can feel so pure and powerful: they’re not about a specific image or narrative, but they tap directly into the brain’s emotional circuits and our primordial responses to pattern and novelty.

Music and Memory: Songs as Keys to the Past

Have you ever had an old song come on the radio and suddenly found yourself transported back to a vivid memory of years past? Music’s link to memory is famously powerful. In people with Alzheimer’s disease or other forms of dementia, this link can be almost miraculous. Even when many memories are lost, musical memory often endures. Neurologists have observed that patients who cannot recognize loved ones or recall recent events can still remember the melodies and words of songs they learned decades ago . Familiar music can “cut through the fog” of dementia, bringing back a sense of identity and awakening emotions that seemed long gone . This happens because music is encoded in the brain differently than other types of memories. Rather than relying only on the hippocampus (the main structure for forming new episodic memories, which is heavily affected in Alzheimer’s), music is stored in a distributed network that includes auditory areas, motor circuits, and the limbic (emotional) system . These overlapping pathways provide multiple backup routes to access musical memories. Brain imaging studies show that key regions tied to musical memory – including parts of the auditory cortex and prefrontal cortex – are among the last to be damaged by Alzheimer’s disease, which helps explain why a beloved song can still spark recognition when other memories fail .

For example, in one famous account described by neurologist Oliver Sacks, a virtually unresponsive Alzheimer’s patient heard an old hymn and suddenly sang along with it, his face coming alive with emotion . Cases like this illustrate that music can tap into a “reserve” of memory. Because a favorite song often intertwines with personal experiences (a wedding song, a lullaby from childhood, an old pop hit from one’s teen years), hearing it again can unlock not just the tune but also the feelings and context associated with it. It’s not uncommon for a melody to bring back a flood of detail – the scene of a first dance, the smell of a summer night, the feelings of a long-ago moment. The brain regions that link music and memory (especially the amygdala and hippocampus) assign emotional weight to these memories, making them more resilient. Even in healthy brains, music is a potent mnemonic device: think of how we teach children the alphabet with a song, or how you might remember a jingle from an old TV commercial effortlessly. The hippocampus and frontal cortex work together when you tie information to music, leveraging rhythm and rhyme to improve recall.

Given these effects, music is increasingly used as a therapeutic tool for memory-related conditions. In nursing homes and memory care units, personalized playlists with an individual’s favorite music often lead to moments of lucidity and joy – a program called Music & Memory has documented how patients will sing, smile, and converse after listening to their signature songs, even if they were agitated or silent beforehand. This isn’t a cure for dementia, of course, but it significantly improves quality of life. Music therapy sessions for Alzheimer’s patients may involve singing familiar songs, which can reduce anxiety and agitation and sometimes improve cooperation with caregivers . The act of singing can also engage language circuits; patients who struggle to speak might still be able to vocalize lyrics, effectively “borrowing” the music’s structure to access words. In fact, this principle is used in stroke rehabilitation as well – a technique known as melodic intonation therapy helps individuals with speech loss (aphasia) by having them sing phrases they cannot say. The melody and rhythm provide an alternate pathway for language, enlisting the right hemisphere of the brain to take over when left-side language areas are damaged . A dramatic example comes from former Congresswoman Gabby Giffords, who after a brain injury struggled to speak; through music therapy, she learned to sing words and gradually regained her spoken language . Melody opened a new neural route for speech – literally rewiring her brain’s language network through song .

Learning, Neuroplasticity, and Cognitive Benefits

Music doesn’t just dredge up old memories; it also helps us learn and shapes the developing brain. Learning to play an instrument or actively engage in music is like brain-training bootcamp – it strengthens a host of mental skills through disciplined practice. Children who undergo musical training often show advantages in memory, attention, and even language skills compared to their non-musical peers . For instance, research has shown that students with musical training perform better on some tests of verbal memory and can switch their attention between tasks more effectively – a sign of enhanced executive function . One long-term study found that young children who took music lessons for just one year exhibited advanced brain development and improved memory compared to those who did not . Their brains showed growth in regions associated with hearing and motor coordination, reflecting how quickly the neural circuits adapt to the demands of music.

These cognitive benefits are thought to arise from the way music engages neuroplasticity – the brain’s ability to rewire itself through experience. Playing an instrument, for example, requires coordination between sensory (listening to the notes) and motor (finger movements or breath control) systems, while also demanding attention, pattern recognition, memory, and even emotion (to play expressively). It’s one of the most complex tasks for the brain, which is why “playing music is the brain’s equivalent of a full-body workout” . Over time, this workout leads to physical changes in the brain’s structure and function. Brain scans of musicians reveal that areas like the corpus callosum (which connects the two hemispheres), the motor cortex, and the auditory cortex can become larger or more efficient than in non-musicians . Musicians often have a greater density of neural connections in regions responsible for fine motor control and auditory processing, showing the imprint of years of practice. Even the hippocampus, important for learning and memory, can exhibit structural plasticity in response to musical training . These changes translate into enhanced abilities: better auditory discrimination, improved motor skills, and perhaps higher capacity for certain types of reasoning.

Importantly, musical training doesn’t just make someone good at music; it appears to have broader cognitive ripple effects. Studies have linked music education to improved language development (children with music training tend to have larger vocabularies and better reading skills) , as well as to better performance in math and spatial reasoning . The mechanisms are still being studied, but one theory is that music strengthens the brain’s executive function – like a mental “core” that helps with problem-solving, attention, and multitasking – which then benefits other domains. Learning an instrument also teaches discipline, patience, and perseverance, which can carry over into academic and life challenges . Even for adults and the elderly, picking up music can be beneficial. Older adults who join a choir or learn an instrument often report improved mood and mental sharpness. There is emerging evidence that such engagement might delay cognitive aging by continually challenging the brain and fostering social interaction.

In the classroom, teachers sometimes harness music as a learning aid. Setting information to a tune (as in educational songs or mnemonic jingles) exploits our brain’s strong memory for music and lyrics. Many of us can effortlessly sing songs from childhood, a testament to how well information sticks when musically encoded. Additionally, playing background music in educational settings can influence concentration: gentle classical music, for example, has been found in some cases to improve focus and reduce stress, although the effect can depend on personal preference and the nature of the task. At the very least, integrating music and arts into education enriches the learning environment and taps into different learning styles, engaging students who might not respond to purely verbal instruction.

Music as Medicine: Therapeutic Healing and Clinical Uses

The therapeutic potential of music is now a recognized field in healthcare, known broadly as music therapy. Clinicians and researchers are leveraging music to address a wide range of neurological and psychological conditions – not as a replacement for other treatments, but as a powerful complement. One reason music works so well in therapy is that it is non-invasive, enjoyable, and engages multiple brain systems at once, including those linked to emotion, movement, and cognition . This makes it a unique way to reach patients who may not respond to traditional therapies. For example, in neurological rehabilitation (rehab for brain injuries, stroke, or degenerative diseases), music can help the brain reorganize. We saw how stroke patients with aphasia use singing to regain speech; similarly, patients re-learning to walk often do so more effectively with a rhythmic soundtrack. A therapist might have a patient time their steps to a beat or practice coordinated movements with music, essentially using rhythm to cue the motor system and enhance plasticity in damaged neural pathways .

In conditions like Parkinson’s disease, where the basal ganglia (a brain area that helps initiate movement) is impaired, external rhythm provided by music can bypass the faulty circuitry. Parkinson’s patients can markedly improve their gait and reduce freezing episodes by walking to music or a metronome – their brains latch onto the steady beat and use it to regulate movement. This phenomenon is so well-supported that music-based movement therapy is an accepted rehab technique for Parkinson’s, improving not only movement but also mood and motivation. Likewise, for patients with multiple sclerosis or those recovering from traumatic brain injuries, music can be tailored to help regain coordination or speech through structured exercises that feel more like art than arduous therapy.

Music therapy is also beneficial in mental health contexts. In depression and anxiety disorders, music can serve as an outlet for expression and a source of comfort. Patients might work with a therapist to identify songs that articulate their feelings, or even write their own music as a form of emotional processing. Listening to music can elevate mood by stimulating dopamine and serotonin, as well as by reducing stress hormones. Clinical studies indicate that incorporating music therapy in treatment plans for depression can lead to reduced symptoms and improved social functioning, as patients find motivation and connection through music-making in group settings. In fact, music’s natural tendency to engage the social brain can counteract the isolation that often accompanies depression. Moreover, relaxing music is commonly used in anxiety and PTSD treatments to help patients regulate their physiological arousal. The slow tempos and predictable patterns act like an anchor, calming racing thoughts and signaling the nervous system to slow down. Many people with anxiety use playlists of calming tracks as a coping tool for insomnia or panic – anecdotally and empirically, it helps slow the breath and heart rate, inducing a relaxation response.

Music’s role in pain management is another fascinating application. Pain is not just a physical sensation but also an emotional experience, and music can modulate both aspects. Hospitals now often offer music therapy to patients with chronic pain or those undergoing painful procedures. As one music therapist explained, music provides a focus that competes with pain signals in the brain, decreasing the perception of pain while also reducing anxiety . Upbeat music might be used in physical therapy sessions to distract from discomfort and increase endurance, whereas soothing music might be played during chemotherapy or burn treatments to help patients relax. The reduction in pain isn’t imagined: research has measured lower pain ratings and even physiological indicators of pain relief (like lower muscle tension) when music is present. Through careful selection of tempo and melody, therapists can synchronize music to a patient’s breathing or heart rate and then gradually slow it, guiding the patient into a more relaxed, less painful state . Furthermore, the positive emotions and memories evoked by favorite songs can flood the brain with competing signals of pleasure or nostalgia, temporarily taking the mind off pain.

Finally, music therapy has shown promise in working with neurodevelopmental disorders like autism. Music can engage children who are non-verbal or highly withdrawn, providing a structure (through rhythm or melody) that encourages interaction. Many children on the autism spectrum respond to songs with predictable, repetitive patterns; they may hum along or use music as a way to communicate when spoken language is challenging. Therapists use musical games to teach social skills, turn-taking (like passing an instrument around), and emotional understanding (using music to represent different feelings). The structured yet non-verbal nature of music can be a comfortable medium for those who find direct social interaction overwhelming.

In all these cases, a key benefit of music in therapy is motivation and engagement. Rehabilitation exercises that might be tedious on their own become more enjoyable when set to music. Patients are often willing to repeat movements more and push a little further when they’re moving to a beat or working towards playing a piece of music. This increased engagement leads to better outcomes. As the American Music Therapy Association emphasizes, music therapy isn’t just about listening to tunes; it’s a goal-directed, clinical intervention delivered by trained professionals to address specific patient goals – whether that’s improving speech, reducing anxiety, or enhancing memory recall . And because music is such a fundamental human pleasure, it often succeeds where other therapies falter, sneaking in “through the backdoor” of the brain . A patient might not be able to endure a half-hour of boring arm exercises, but give them a drum to beat in time to a song and they’ll exercise that arm for far longer without noticing the strain.

Cultural Connections: Universality and Diversity in Musical Experience

Music is a universal language of humanity – every culture on earth has some form of music – yet it is also incredibly diverse in style and tradition. This dual nature means that our brains are hardwired for music broadly, but they are also shaped by the specific sounds we grow up with. On the one hand, there are striking universals in how music affects the brain across cultures. Research has demonstrated that people from different parts of the world feel similar emotions from the same basic musical cues. A recent cross-cultural study found that Western and Chinese listeners reported very similar emotional and physical sensations when hearing the same pieces of music, even though the music came from unfamiliar traditions . Happy music made both groups feel energized and stimulated throughout the body (lots of warm, active feelings in the limbs), while sad music was felt more as a heavy sensation in the chest and head by everyone . The correlations in their responses were very high, indicating a shared human emotional response pattern to fundamental musical qualities. Another example of universality is the lullaby: nearly every culture has gentle, soothing songs to calm infants, and studies show that even foreign lullabies tend to have a calming effect on babies (and adults) who have never heard them, presumably because our brains recognize the soft dynamics and simple, slow rhythms as “relaxation signals.”

People from different cultures experience similar patterns of bodily sensations in response to music. In one study, Western and East Asian participants indicated where they felt various emotions from music in their bodies. Warm colors (yellow/white) show regions of increased sensation. Both groups felt upbeat “happy” or “danceable” music as energizing nearly everywhere (notably in the limbs), while “sad” or “tender” songs were felt more in the head and chest. The strong similarity (high correlation r values) between cultures suggests universal physiological responses to musical emotions .

On the other hand, our musical preferences and perceptions are profoundly shaped by cultural exposure. The brain refines its musical “ear” based on the scales, harmonies, and rhythms it hears regularly. One striking study by MIT scientists showed that what sounds pleasant or unpleasant can depend entirely on familiarity: members of an isolated Amazonian tribe did not share Western participants’ dislike for dissonant chord combinations. To their ears, a clashing chord (like C and F# played together) was just as acceptable as a smooth harmonic chord, whereas Westerners consistently found the dissonant combination jarring . This suggests that the brain’s aversion to dissonance (often assumed to be innate) is actually learned through cultural listening – our neural networks get trained to expect certain intervals as “normal” and label others as tense or unpleasant. In Western music, we have been inundated with the sounds of the major/minor system and consonant chords, so our brains come to crave those patterns. But someone raised outside that system might have an entirely different musical framework. Indeed, musical scales and tunings vary worldwide (from the microtones of Indian ragas to the five-tone scales of traditional East Asian music), and listeners’ brains adeptly attune to the nuances of their native music system.

Cultural context also influences the meaning and use of music, which in turn affects the brain. For example, in some Indigenous cultures, repetitive drumming and chanting are used in trance and healing ceremonies, effectively harnessing rhythm to induce altered states of consciousness – a testament to how rhythm can drive brainwave patterns into specific states (like a meditative or trance-like theta wave state). In Western cultures, a stadium rock anthem might trigger euphoria and a sense of unity among thousands of fans – a modern analog of ancient communal music rituals. In each case, the social significance attributed to the music modulates the listener’s brain response. If you associate a national anthem with patriotism and pride, hearing it will light up brain circuits tied to identity and emotion more than it would for someone from another culture. Our medial prefrontal cortex, which helps attach personal meaning to music, is especially active for songs that are personally or culturally important to us .

Despite these differences, music often serves similar functions across humanity: it brings people together, marks important occasions, soothes the afflicted, and communicates feelings when words fall short. The social bonding effect of music seems to be universal. When people sing or make music together, it breaks down barriers. Studies in the UK found that group singing in a choir, even among complete strangers, quickly builds feelings of connectedness and trust. This happens in part due to neurochemistry: singing together triggers the release of endorphins and oxytocin, chemicals that promote social bonding and affection . One study measured pain threshold as a proxy for endorphin release (since endorphins raise our pain tolerance) and found that after group singing or drumming sessions, participants had higher pain thresholds and felt more bonded as a group . Interestingly, larger groups singing together showed an even bigger boost in bonding hormones and sense of unity than smaller groups . This suggests music has an almost exponential power to build community – something long exploited in human culture, from religious hymns to folk dances to national anthems. Our brains appear wired to synchronize not just to a beat, but to each other when music is the common medium . The rhythmic synchrony of making music in a group (even simply clapping or swaying in unison) fosters empathy and cooperation; experiments have shown that after moving in sync to music, children and adults alike are more likely to help each other and feel a mutual rapport .

In a sense, music’s cultural dimension highlights a beautiful paradox of the brain: we all have a built-in musical blueprint (children everywhere respond to lullabies, brains everywhere release dopamine to pleasing rhythms), yet our individual musical brains are also products of our unique cultural experiences (shaped by the scales, songs, and emotions we grew up with). Neuroscientists tackling the “nature vs. nurture” of music suggest it’s really both: our brains have natural musical biases (nature), but they are refined by neural plasticity to fit the musical environment we’re nurtured in . That’s why Neural Resonance Theory posits that certain patterns like a steady pulse or perfect harmony might resonate as stable states in almost any human brain, providing common ground across cultures, while the specific music we prefer is largely what we’ve been taught to love . Ultimately, the cross-cultural appeal of music – a song like “Happy Birthday” or Beethoven’s Ode to Joy being recognizable and emotive to people worldwide – speaks to an underlying biological response to organized sound. And at the same time, the rich tapestry of global music shows the brain’s adaptive creativity, capable of finding meaning and beauty in an astonishing variety of sound patterns.

Conclusion: A Symphony of Brain and Sound

From the thumping drums that get our hearts pumping, to the melodies that bring tears or smiles, music engages the brain on every level. It is at once a motor exercise, an emotional journey, a memory cue, a learning tool, and a social glue. Modern neuroscience validates what humans have intuitively known for ages: music moves us because our brains literally dance to its rhythms, resonate with its harmonies, and find narrative in its melodies . This intimate coupling between music and the brain explains music’s therapeutic potency – how it can help heal injured brains, lift depressed spirits, or unlock lost memories. It also explains music’s enduring presence in every culture: it speaks to something fundamental in our neural wiring that craves rhythm and pattern, connection and expression.

As research advances, we continue to discover new dimensions of music’s influence on the brain. Therapists are developing targeted musical interventions for conditions ranging from Alzheimer’s to autism. Educators are integrating music to enhance cognitive development and attention. Even technology is getting in on the act, with AI being trained to compose music that aligns with our brain’s emotional dynamics . We stand at an exciting intersection of art and science, where understanding the brain not only unravels the mystery of music’s power but also equips us to harness that power in improving lives.

In the end, perhaps the true wonder is how deeply human music is: it engages our cortex and our primitive brain, our thoughts and our emotions, our individuality and our community. The next time you find yourself humming absentmindedly or swaying to a song on the radio, remember – it’s not just in your head. Your entire brain is participating in a symphony, with neurons firing in harmony to the beat and melody. Music is literally changing your brain state moment by moment, for the better. It’s no exaggeration to say that music leaves an imprint on the brain – sometimes fleeting (the quick mood boost from a fun tune), sometimes lasting (the structural brain changes after years of practice), and often profound (the song that comforts you in grief or fills you with inspiration). The human brain is the most sophisticated musical instrument in the world , and music is the language it speaks to heal, to remember, to learn, and to feel. In this intricate duet between neural circuits and sound waves, we find the essence of why music matters – it resonates within us, literally and figuratively, in a way that shapes our minds and enriches our lives .

Sources: The information in this article is grounded in scientific research and expert insights, including studies on neural resonance and rhythm , the role of dopamine in musical pleasure , clinical applications of music in therapy , the impact of music training on brain plasticity , and cross-cultural research on music and emotion , among others.