Aging Isn’t a Side Issue — It’s the Heart of the Matter

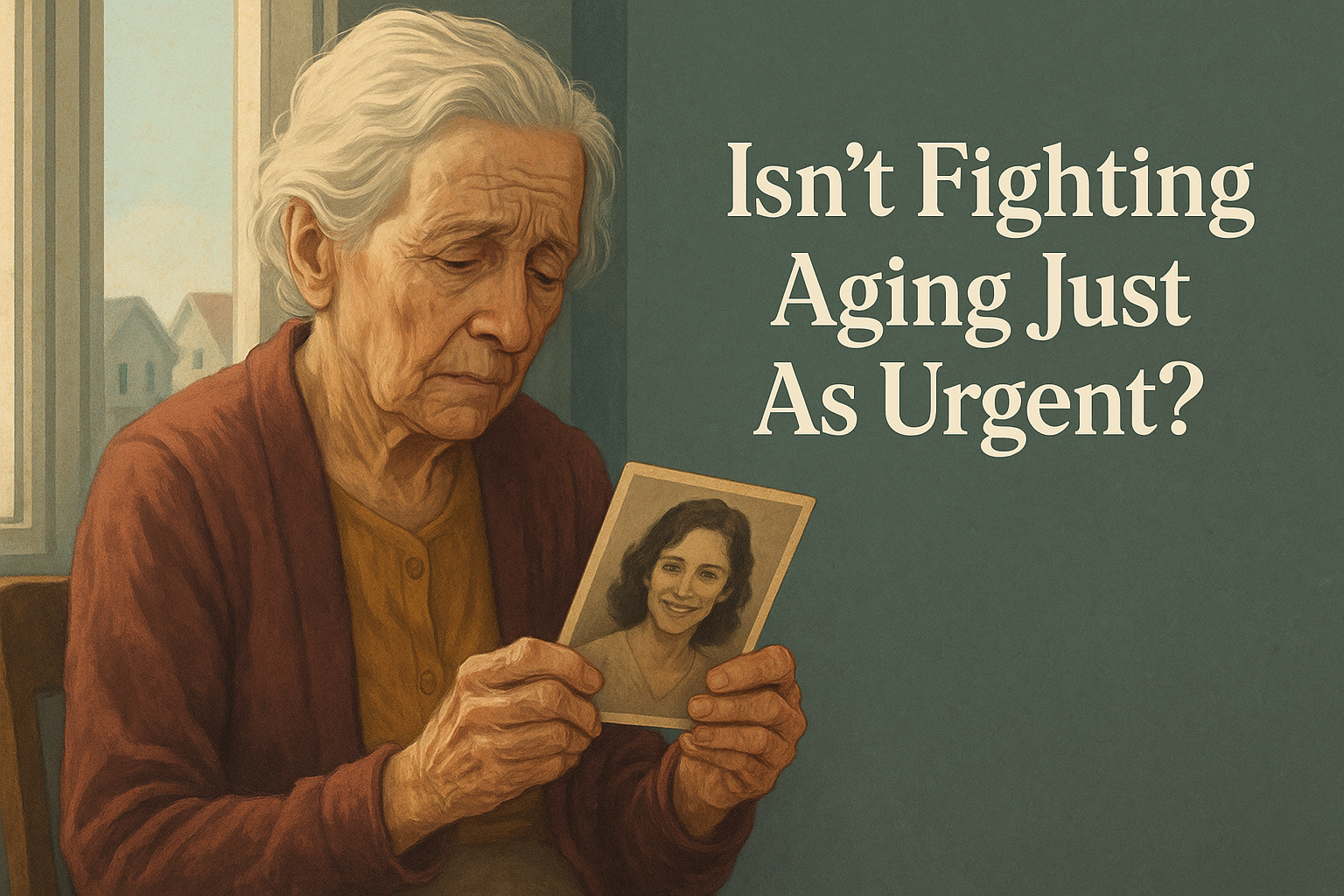

In a quiet corner of Evergreen, an eighty‑two‑year‑old teacher named Elena is losing her grip on life. Her hands tremble around a faded photograph; arthritis flares through her wrists, pills for high blood pressure leave her dizzy, and the fog of dementia steals names and faces. Her son, Marco, sits nearby listening to the evening news. A reporter talks about a malaria outbreak far away and the hundreds of children it has claimed. Marco turns to his wife and whispers, “Maybe we should worry about diseases like malaria before we pour money into anti‑aging research.”

Elena hears him. The look on her face says what she cannot find the words to tell him: that her suffering is real, that the slow march of aging is itself a lethal epidemic. Marco’s question echoes a common belief—that diseases like malaria or tuberculosis are more urgent, while aging is a natural inevitability we must accept. This view seems compassionate on the surface, yet it falls into a trap philosophers call relative privation: dismissing one issue simply because another looks worse. To use a simple analogy, arguing that we shouldn’t repair a leaking roof because the basement is flooding makes no sense; both problems deserve attention, and leaving the roof to rot will only worsen the flood.

The scale of suffering

Global health data show why this is a false choice. Chronic diseases—heart disease, stroke, cancer, diabetes and other disorders linked to aging—cause over 41 million deaths each year, accounting for about 74 % of all deaths worldwide . That translates to roughly 112 000 people per day succumbing to age‑related illness. In contrast, malaria, though devastating for children in sub‑Saharan Africa, caused about 608 000 deaths in 2022 (around 1 600 deaths per day) . Put differently, the diseases of aging kill more people every two or three days than malaria does in an entire year. Ignoring aging because other diseases exist misses the staggering human toll inflicted by “normal” decline.

This isn’t about minimizing the tragedy of malaria. Young lives lost to preventable infections are heartbreaking, and global campaigns deserve our support. What makes aging research urgent is that it strikes everyone, everywhere. When you add up deaths from heart attacks, cancers, strokes, Alzheimer’s and other disorders that share common biological mechanisms, you see a universal vulnerability. Fighting aging is not about vanity or immortality; it is about preventing the cascade of illnesses that rob millions of their independence and dignity.

Aging is not inevitable — it has causes

Modern biology has dismantled the myth that aging is beyond our control. Scientists have identified nine “hallmarks” of aging—processes like genomic instability, telomere shortening, epigenetic changes, mitochondrial dysfunction and cellular senescence . These hallmarks drive the gradual decline in tissue function. One of them, cellular senescence, occurs when damaged cells stop dividing and begin secreting inflammatory molecules. While this response protects against cancer, senescent cells accumulate in tissues over time. They promote atherosclerosis by impairing blood vessels , drive cartilage degeneration and pain in osteoarthritis and even support tumour growth by releasing cytokines like IL‑6 and IL‑8 . Senescent cells hinder stem cells, fuel chronic inflammation and contribute to osteoporosis, type 2 diabetes and neurodegeneration .

The good news is that removing or modulating senescent cells works. Senolytic drugs, designed to clear these cells, improve physical function and resilience in animal models and reduce all‑cause mortality even when given late in life . Because senescence lies at the root of many chronic diseases, targeting it yields benefits across organs—something that conventional “one disease, one drug” approaches cannot match .

Other interventions developed through aging research show similar breadth:

- Metformin, a common diabetes drug, reduces insulin resistance, lowers inflammation and improves cardiovascular and cognitive health . Studies indicate that metformin may activate cellular repair pathways, preserve telomeres and reduce cellular senescence . These effects help not only older adults but also middle‑aged people at risk for metabolic diseases.

- Rapamycin, originally discovered as a soil bacterium, was approved in 1994 to prevent organ rejection in liver transplant patients . Researchers later found that rapamycin targets the mTOR pathway, a master regulator of cellular growth and metabolism. In 2009 it extended lifespan in male and female mice, even when administered late in life . Today rapamycin and related drugs (“rapalogs”) are used to prevent restenosis after coronary angioplasty and are being tested as cancer therapies .

- Telomerase research once aimed to understand why telomeres—the protective caps on chromosomes—shorten with age. It yielded unexpected dividends: Imetelstat, a first‑in‑class telomerase inhibitor, selectively kills malignant blood‑cell clones and was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in June 2024 for certain myelodysplastic syndromes . This cancer therapy grew directly out of basic studies on aging.

These examples illustrate a pattern: When we investigate aging, we uncover therapies that impact diverse diseases. Rather than competing with malaria research, aging research multiplies our medical options.

Biology connects all diseases

Why does treating aging help so many disorders? Because many diseases share the same upstream causes. Chronic inflammation, mitochondrial decline, DNA damage and stem‑cell exhaustion are threads that weave through cardiovascular disease, neurodegeneration, frailty and even susceptibility to infections. This is why slowdowns in aging can delay multiple diseases at once.

Consider the immune system. Older adults suffer more severe outcomes from infections like influenza and malaria partly because their immune cells are themselves aged. Interventions that rejuvenate immune function could reduce deaths from infectious diseases as well. Gut health offers another example. Research on how aging alters the microbiome has led to fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). FMT restores healthy bacteria in the intestine and can be more effective than antibiotics for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection, which disproportionately affects older patients and can be fatal . Experiments transferring gut bacteria from long‑living people to mice reduced inflammatory markers and improved survival, suggesting that microbiome-based therapies could slow aging and enhance resistance to diseases .

Scientists are also developing epigenetic clocks, tools that read patterns of DNA methylation to estimate a person’s biological age. These clocks predict mortality and age‑related disease risk more accurately than chronological age . They enable earlier intervention and personalized medicine: if we can measure aging, we can test whether a therapy truly slows it down and identify individuals at high risk for disease years before symptoms appear.

The resource argument falls apart

Some critics worry that focusing on aging will divert money from pressing global needs. This argument collapses upon inspection. Governments and private donors are not forced to choose one cause exclusively; resources are not a single pie, and the same philanthropists often fund multiple efforts. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, for example, has contributed nearly US$4 billion to the Global Fund, pledging hundreds of millions more to fight HIV, tuberculosis and malaria . Yet much smaller sums go toward rejuvenation research. Basic aging biology remains one of the least funded areas of the National Institute on Aging , and many promising studies rely on private non‑profits. Even the SENS Research Foundation, a leading organization dedicated to reversing age‑related damage, operates on just a few million dollars per year . By contrast, the Ellison Medical Foundation’s philanthropic program—one of the few substantial funders of basic aging science—distributes around US$40 million annually to 200 labs, which its director notes is a drop in the bucket compared to disease‑focused budgets .

Treating aging is not a vanity project; it is arguably the most cost‑effective way to reduce disease burden. Slowing the aging process by even a single year could save trillions of dollars in healthcare costs and productivity losses—resources that could then support malaria prevention, clean water projects and education. There is no ethical rule requiring us to ignore a problem that kills 110 000 people daily simply because another problem kills 1 600.

A broader ethic of care

Recognizing aging as an urgent issue does not diminish compassion for children dying of malaria, nor does it imply neglecting other health crises. Instead, it invites a holistic ethic. Imagine if Elena’s arthritis and dementia were treatable at their root; she could again share her stories and wisdom with Marco and his children. Imagine if treatments that rejuvenate immune systems in the elderly also improve vaccine responses in young malaria patients. When we talk about “curing aging,” we are really talking about preventing the underlying damage that drives most diseases.

The Lifespan Research Institute’s argument against the appeal to worse problems is therefore not academic; it speaks to everyday realities. The debate isn’t about ranking tragedies but about recognizing interconnectedness. If we slow aging, we reduce the toll of heart disease, cancer, strokes, Alzheimer’s, osteoarthritis and even infectious disease deaths. Aging research is a linchpin for medical progress, and dismissing it because malaria exists is like refusing to fix a bridge because a highway also needs repair. Both efforts are essential, and the bridge may support ten other roads.

Conclusion: A shared future

Elena’s story is a reminder that aging is personal. It affects our parents, ourselves and—if we are fortunate to live long enough—our children. In the coming decades, populations worldwide will skew older. Without interventions, more families will watch loved ones fade under the weight of multiple chronic diseases. We have the knowledge and the tools to prevent much of this suffering. Scientists are deciphering the mechanisms of aging, developing drugs like metformin and rapamycin that improve health across organs, designing senolytics to clear harmful cells, harnessing gut bacteria to rejuvenate tissues, and building epigenetic clocks to guide personalized care.

We do not have to choose between saving Elena and saving a child with malaria. We can and must do both. Rejecting the false hierarchy of problems frees us to invest in solutions that have the widest reach. Prioritizing aging research is not a diversion from urgent humanitarian work; it is a strategic imperative that amplifies the impact of every other health intervention. As compassionate citizens and readers, we should urge policymakers and philanthropists to see aging as what it is: a treatable cause of disease and suffering, not a background condition we are doomed to endure.

Discover more from RETHINK! SEEK THE BRIGHT SIDE

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.