Introduction

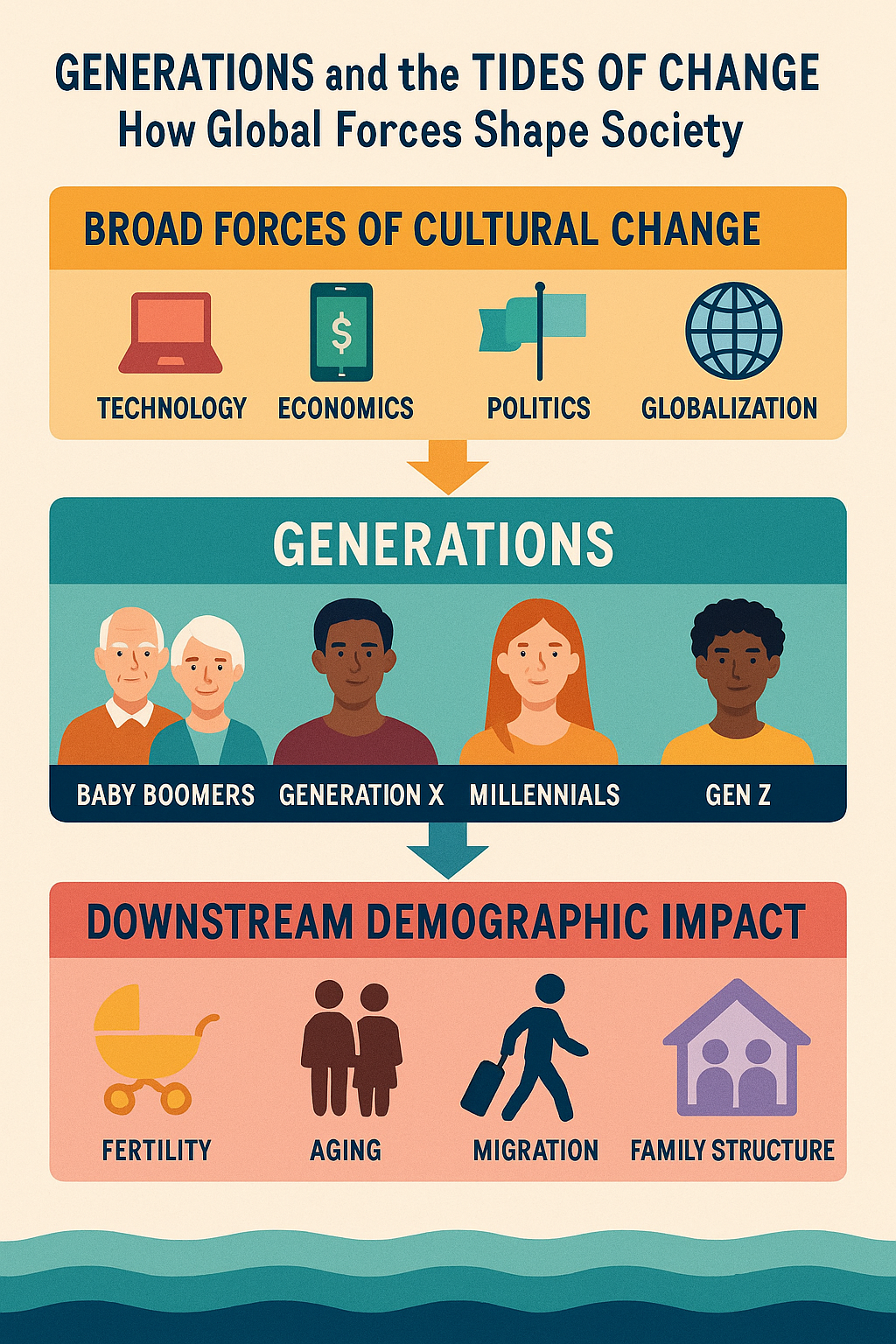

On a warm evening in 2025, a grandmother and her granddaughter sit together in a busy Nairobi café. One scrolls through news on her smartphone, while the other recalls listening to world events crackle over a communal radio in the 1960s. The gap between their experiences is vast, yet it illuminates a powerful truth: broad cultural forces – from technological revolutions to economic upheavals, political shifts, and globalization – drive societal change, leaving distinct imprints on each generation. Sociologists often talk about generational cohorts like the Baby Boomers, Generation X, Millennials, and Gen Z to make sense of these changes. Each cohort grows up in a unique zeitgeist that shapes its values and choices. Understanding those cohorts gives us clarity on how sweeping changes influence individual behavior – from how we form families to where we live and work. This narrative explores how technology, economics, politics, and globalization have molded different generations around the world, and how these dynamics are reshaping long-term demographic patterns such as birth rates, migration, aging, and family structures. It’s a journey through time and across continents, showing how the experiences of today’s youth and elders are bound together by the tides of change, and what that means for our collective future.

Technology and Transformation Across Generations

Technology is one of the most visible drivers of societal change – and its impact differs greatly by generation. The grandmother in our story might marvel at the smartphone in her granddaughter’s hand; after all, she grew up when a single telephone in a village was a luxury. For Baby Boomers (born roughly 1946–1964), transformative technologies included television and the first computers. Many Boomers remember the moon landing broadcast on fuzzy black-and-white TVs, or writing letters by hand. Gen X (born ~1965–1980) witnessed the rise of personal computers and the dawn of the internet in their youth. Millennials (born ~1981–1996) came of age alongside the internet revolution – they recall the screech of dial-up modems and the excitement of their first mobile phones. And Gen Z (born ~1997–2012) are true digital natives, never knowing a world without smartphones, social media, and instant connectivity. These differences matter. A Millennial doctor, for example, is part of the first generation of physicians that grew up with smartphones and social networks integrated into daily life . What this means is that younger generations tend to adapt quickly to new tools – nearly all young adults today spend time on social media daily (about 94% do) – while older generations have had to learn these tools in mid-life. The result is a cultural shift in how people communicate, learn, and even form their identities. A Gen Z teenager in Mumbai can chat in real time with a peer in London about the latest K-pop album or global news, forging a shared global youth culture in a way that was science fiction for prior generations. Technology has essentially shrunk the world and accelerated the pace of cultural exchange for the young. At the same time, it’s bridging gaps between generations in unexpected ways – consider how Baby Boomers and Gen X are redefining retirement by launching businesses in their 60s or finding new love through dating apps in their 70s . The spread of the internet and digital tools has empowered people of all ages, but it’s the youth who have been the pioneers of this connected era. This global connectivity – from satellite TV in remote villages to smartphones nearly everywhere – has created both a common generational experience across countries and a new divide between those comfortable in the digital world and those who recall a more analog time. In short, technology’s relentless march has been a powerful tide lifting and sometimes rocking the boats of generational change.

Economic Booms, Busts, and Life Choices

If technology determines how we connect, economics often determines what choices feel possible. Broad economic forces – prosperity or recession, job security or uncertainty – shape the milestones of each generation. The Baby Boomers, in many countries, grew up in unprecedented post-World War II prosperity. In places like the United States and Western Europe, the post-war economic boom meant stable jobs, rising wages, and affordable housing for young families. Many Boomers could follow a predictable life script: get a stable job, marry early, buy a home, and have children – all by their mid-20s. Indeed, during the baby boom years mid-century, people started families much earlier than today. In the United States, for instance, a majority of young women (ages 20–24) were already married by 1960, a sharp increase from a generation prior . This pattern was echoed in other countries; early marriage and a steady job were attainable milestones for many in that era. Fast-forward to the Millennials and Gen Z, and the economic landscape looks very different. Globalization and automation have created immense opportunities – a young entrepreneur in Lagos can code an app that reaches a worldwide market – but also new uncertainties. The late 2000s brought a global financial crisis that hit many Millennials just as they entered the job market, leaving scars of underemployment and student debt. Housing costs in global cities skyrocketed, making it hard for young people to afford homes. Stable lifelong careers gave way to the gig economy and frequent job changes. In fact, the notion of a “job for life” has faded: nearly 60% of young adults globally believe they will work for between 2 and 5 different organizations in their lifetime . With longer education periods and less economic security in early adulthood, Millennials and Gen Z have often delayed the traditional milestones. But it would be wrong to call them simply “delayed” or “behind” – they are, as one global study put it, rewriting the script of adulthood . “The old early adulthood script — graduate college, land a stable job, marry, buy a house, have children, retire at 65 — is being rewritten by a generation that asks not ‘When should I?’ but ‘Why should I?’” the study observes . In other words, younger generations are making deliberate choices, shaped by pragmatism amid new economic realities. They prioritize financial independence and personal fulfillment in novel ways – for example, surveys show 87% of today’s young adults say being financially independent is highly important, yet they might achieve it through unconventional careers or side-hustles . Economic forces thus push each generation onto slightly different life paths: where Boomers might have felt confident in a pension and started families in their early 20s, Millennials and Gen Z navigate a world of contract work, startup dreams, and the question of not just when to start a family or buy a house, but whether it makes sense in their current world. These economic tides have profound effects on personal values and lifestyles – engendering, for instance, a frugal mindset and entrepreneurial spirit in many Millennials who came of age during recession, or a global job-hopping mindset among Gen Z who compete in an international talent pool.

Politics, Global Events, and Shifting Values

Politics and major world events are another powerful current shaping generational outlooks. Each generation’s values are forged in the fires of the events they witness in their formative years. Baby Boomers in many countries grew up in the shadow of the Cold War and, in the West, the optimistic era of space exploration and civil rights movements. Many in this cohort were idealistic young adults in the 1960s and 70s who protested against wars or fought for social change. In contrast, Gen X spent their youth in the late Cold War and saw the fall of the Berlin Wall, often developing a skeptical, independent streak (earning a “slacker” reputation in the 1990s that belied their adaptability). Millennials globally had a front-row seat to events like the 9/11 attacks and the ensuing wars, which spurred a mix of insecurity and global awareness, and they witnessed the 2008 economic crash, which eroded trust in financial institutions. Gen Z, meanwhile, has come of age amid a chaotic stream of news: terrorism, a pandemic, political polarization, and the ever-present reality of climate change. These events influence how generations view authority, community, and the future. Consider climate change, arguably the defining global challenge of our time: young people have rallied worldwide to demand action, from the Fridays for Future school strikes to youth-led climate lawsuits. Surveys show Gen Z is among the generations most concerned about climate change – in one Pew Research Center study, 76% of U.S. Gen Z respondents said climate change is one of their biggest concerns (37% even called it their top concern) . Older generations, by contrast, may care about the environment but generally did not list it as urgently in their youth; it wasn’t as visible an issue when they were young. This doesn’t mean values are monolithic by age – many Boomers became environmental activists and many Gen Z are politically diverse – but each cohort’s center of gravity shifts with the issues that dominate their youth. Politics itself also responds to generational turnover. As younger cohorts who are more diverse and globally minded reach voting age, political cultures begin to change. For example, policies on social issues (from LGBTQ rights to cannabis legalization) that might have been fringe in a grandparent’s era find majority support among millennials and Gen Z. In democratic societies, youth movements have often been catalysts for change – from the anti-apartheid rallies led by young South Africans in the 1980s, to the recent pro-democracy protests energized by students in places like Hong Kong and Chile. Even in more traditional societies, the voice of youth, amplified by social media, is pressuring leaders to adapt. At the same time, older generations in many countries hold significant political power through sheer numbers and voter turnout – hence debates over pension reforms or Brexit often exposed a generational divide, with younger citizens favoring different futures than their elders. In short, politics and generational change are entwined: global events shape each cohort’s fears and hopes, and as those cohorts come of age, they in turn reshape politics. Understanding that, for example, Millennials entered adulthood amid war and recession helps explain their caution and desire for change, just as understanding that Boomers saw post-war rebuilding and the rise of national institutions helps explain their trust in certain social structures. Appreciating these differences fosters dialogue and empathy between generations – a necessary step as societies navigate the challenges that affect everyone, young and old.

Globalization and the First Global Generation

Towering over technology, economy, and politics is the giant wave of globalization – the increasing interconnectedness of our world. Globalization has economic dimensions (trade, multinational businesses), cultural ones (the spread of music, movies, and ideas), and human dimensions (migration and travel). While globalization has been building for centuries, the late 20th and early 21st century have accelerated it dramatically. Generations alive today, especially the young, are arguably the first to experience a truly global culture. A teenager in São Paulo might stream the same Korean pop song as a teenager in Seoul, while a coder in Nairobi collaborates online with a team in Berlin. For older generations, this level of cultural convergence is astonishing. In an EY global study, researchers dubbed today’s youth “the first truly global generation, connected by shared experiences, challenges and aspirations that transcend geographical boundaries.” Young adults around the world today often have more in common with each other than with their parents when it comes to pop culture, communication styles, and even aspirations . Why? Because globalization – turbocharged by the internet – gives them access to the same information and platforms. Social media brings far-flung individuals into the same conversations. English and other lingua francas spread via global media, enabling cross-cultural dialogues. This doesn’t erase local cultures, but it adds a layer of global identity on top of them. Globalization also means migration has become a defining experience of this era. People move more freely (or at least more frequently) across borders for education, work, or refuge than ever before. The numbers tell a striking story: the number of people living outside their country of birth nearly tripled from about 108 million in 2000 to 281 million in 2020 . Young adults are often at the forefront of this trend – whether they are skilled workers seeking opportunities abroad, or students studying overseas and forming international social circles. Migration can profoundly affect family structure and cultural identity: a young couple from South Asia starting a life in Canada might blend traditions, while their parents back home adapt to grandparenthood via video calls. Globalization’s flip side has been a reaction in some places – a rise in nationalist sentiment and questions about cultural identity, often more strongly voiced by older generations who see familiar ways of life changing. Yet, even this tension underscores how transformative the global mixing of people and ideas has been. For example, consider how cuisines, fashions, and languages have traveled: it’s not unusual for a Millennial in Europe to eat Thai curry for lunch, wear clothes made in Bangladesh, work for a company headquartered in Silicon Valley, and discuss Korean cinema in the evening. Such a lifestyle would be bewildering to her great-grandparents. And for Gen Z, this hybridity is the norm. This first global generation is navigating the benefits and challenges of a world where distance matters less. They are more likely to see themselves as “global citizens,” to have friends from different countries, and to view issues like pandemics or climate change as shared global problems requiring cooperation. The experience of the COVID-19 pandemic, in fact, was a simultaneous global event that every generation went through together – but even there, young people perhaps had the novel experience of remote learning and TikTok-fueled quarantine trends shared worldwide, deepening that sense of a global cohort. Globalization, then, is both a uniting force and a source of generational distinction. It creates a common planetary culture among the young, while challenging older norms of community and identity. And importantly, it feeds back into the other forces: it drives technological spread, economic opportunity and competition, and political debates on immigration and trade.

Shifting Demographics: Family, Fertility, and Aging in Flux

One of the clearest ways to see the impact of these broad forces is to look at demographic patterns – how people form families, how many children they have, where they live, and how societies age. These patterns are the cumulative result of millions of individual choices, which in turn are shaped by cultural values and economic realities. By examining them through a generational lens, we gain insight into how deeply society has changed and where it might be headed. Consider birth rates and family size. In the mid-20th century, many parts of the world experienced a “baby boom.” Broadly defined as the post-WWII surge in births (roughly 1946–1964 in the U.S. and similar periods elsewhere), the baby boom was fueled by a mix of optimism, young marriage, and improving health and prosperity . It wasn’t just an American phenomenon – countries from Sweden to Australia saw birth rates climb in the same era, suggesting shared global forces were at work . Birth rates in the U.S., for example, peaked in the late 1950s at roughly 3.7 children per woman, and worldwide, the total fertility rate around 1950 was about 5.0 births per woman . Families were large, and it was common for couples to have children soon after marriage, often in their early twenties. Fast-forward to today, and you’ll find a very different picture. Globally, fertility has fallen steeply – to about 2.4 births per woman by 2020 – and in dozens of countries it’s well below the “replacement” level of 2.1 needed to maintain a stable population. This shift from big families to smaller ones (or childlessness by choice) is a hallmark of the generational transition from Boomers to Millennials. Why did it happen? Part of the answer lies in those broad forces we discussed: improved education and career opportunities (especially for women), economic pressures, access to contraception, and changing cultural priorities. Young people today often delay marriage and childbirth as they pursue higher education and navigate careers. In many countries, the average age of motherhood has climbed into the late 20s or 30s, whereas during the baby boom it was common to start a family before age 25 . For example, in some high-income countries, the average age at first birth now hovers around 30 . This doesn’t necessarily mean Millennials and Gen Z don’t value family – rather, they are having children later (and fewer) due to a combination of personal choice and circumstance. They ask “why (and when) should I have a child?” in a way that their grandparents, who took it as a given early in adulthood, did not . The result is a profound demographic shift: smaller households are on the rise globally, and one-person households or childfree couples are increasingly common, especially in urban areas . Family structures themselves have diversified. The Baby Boomer era idealized the “nuclear family” (a married mom and dad with kids), but later generations have seen higher rates of divorce, more single-parent families, and more couples living together without marriage. In the United States, for instance, the share of births to unmarried mothers has climbed from about 10% in 1970 to roughly 50% in recent years . In many societies, LGBTQ+ couples are raising children openly now, and multi-generational households are making a comeback in places where young adults live with parents longer due to economic necessity or cultural preference. All these trends reflect how broad forces alter personal life: economics might keep a 30-year-old living at home longer, politics and social movements have expanded the definition of family, and globalization means a person might find a partner from a different country, blending cultures under one roof. Perhaps the most dramatic demographic effect of generational shifts is population aging. When birth rates fall and life expectancy rises, populations age – meaning a larger share of people are older. The Baby Boomers, being a large cohort, are now entering their retirement years in many countries, creating an “age wave.” At the same time, younger, smaller cohorts are replacing them. Globally, we have reached a striking milestone: In 2018, for the first time in recorded history, the number of people over 64 years old exceeded the number of children under 5 . This crossover is an emblem of how different the world of Gen Z will be compared to that of their great-grandparents. In aging societies like Japan, Italy, or South Korea, school classrooms are shrinking while nursing homes are filling up. Japan offers a vivid example – in 1950, over half of Japan’s population was younger than 25, reflecting a pyramid-shaped youthful age structure. By 2021, after decades of low birth rates, the share of young Japanese had plummeted, and those over 65 comprised a significant portion of the population . Meanwhile, in a youthful country like Nigeria, the story is different: Nigeria’s median age is still under 20, and children and youths dominate the demographic profile. Such contrasts show that generational forces play out differently across the globe – some societies are grappling with too few babies, others with still rapidly growing young populations. Aging populations pose challenges that will test generational solidarity. Fewer working-age people supporting more elderly means potential economic strain on pension and healthcare systems . It also means cultural shifts: the concept of retirement, elder care, and the role of grandparents are all evolving. Encouragingly, as noted earlier, older generations are also redefining aging – staying active and even starting new ventures late in life – which could mitigate some pressures if societies adapt. Finally, we should note how migration ties into demographic change. With youthful populations in some regions (like sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia) and aging populations in others (like Europe and East Asia), migration can act as a balancing force. Young workers moving from a country with surplus labor to one with labor shortages can benefit both. Already, many countries rely on immigrant workers to fill gaps in everything from tech jobs to eldercare. Migration has surged in the 21st century, as mentioned, and much of it is driven by young adults . This flow of people not only affects population numbers but also spreads cultural values and ideas between generations and societies – a family that migrates may adopt some values of their new home while preserving traditions from their old, creating a rich tapestry of cultural change. But migration can also lead to brain drains in countries left behind and social tensions in receiving communities. Understanding the generational aspect – that many migrants are young people seeking opportunity – can inform better policies that bridge generations and cultures. In sum, by looking at births, aging, family, and migration, we see the fingerprints of broad forces on the most intimate aspects of life. Every statistic – be it a declining birth rate or a growing number of centenarians – tells a human story influenced by when and where people grew up. And these demographic shifts themselves feed back into society, prompting new cultural norms (for example, normalizing later motherhood or making aging issues more central to politics).

Looking Ahead: Generational Shifts and Our Collective Future

Standing at the midpoint of the 21st century’s third decade, we find ourselves at a crossroads of generational change. The world that is coming into focus for the next few decades will be shaped by the values and choices of the cohorts now coming of age – as well as the wisdom and influence of those who came before. What might this future look like? Our exploration of broad forces offers some clues. Technology will likely continue to knit the world closer together, with Gen Z and the emerging Generation Alpha (born in the 2010s) pushing the frontiers of artificial intelligence, biotechnology, and whatever comes next. The economy will be forced to adapt to both a youth scarcity in aging countries and a youth boom in others; companies and governments may need to court Millennial and Gen Z workers with new policies (from remote work to mental health support) to harness their productivity in a time of rapid change . Politically, as Millennials and Gen Z become the largest voting blocs in many democracies, we can expect their priorities – whether climate action, social justice, or digital freedoms – to increasingly shape agendas. Already, Millennials have surpassed Baby Boomers as the largest adult generation in the United States , signaling a passing of the torch that will echo in many nations. Globally, we may see a new balance of power as youthful countries in Africa and South Asia rise economically and politically, while older nations grapple with supporting their aging citizens. The generational lens also suggests a hopeful insight: each generation, having been molded by different circumstances, brings something new to the table. Boomers carry institutional knowledge and the experience of how far we’ve come. Gen X offers a bridge of pragmatism and an often underappreciated adaptability. Millennials bring collaborative spirit and a drive to address the unfinished business of previous eras (from financial reform to inclusivity). Gen Z injects idealism and digital nativity, refusing to accept that “this is how it’s always been” – they are, as one commentator put it, not interested in checking the traditional boxes just for tradition’s sake . Instead, they ask how systems can work better for a changing world. This interplay can be fruitful. For example, we may see multigenerational collaborations become the norm: start-ups that pair Gen Z innovators with Boomer mentors, or community projects where youth and elders learn from each other (as is already happening in intergenerational housing initiatives in Europe and beyond). The narrative of conflict between young and old is giving way to one of mutual influence, especially as societies recognize that problems like climate change and pandemics do not discriminate by age. As we look to the horizon, one thing is certain: societal change is continuous, but understanding it through the prism of generations gives us a map. It shows us how yesterday’s decisions led to today’s realities – how a post-war boom led to the population aging of 2025, or how the delayed marriages of Millennials are linked to the low birth rates troubling many nations’ planners. It also helps us anticipate tomorrow. Long-term demographic patterns, from shrinking youth populations in East Asia to expanding cities in Africa, will shape the job markets, political clout, and cultural vibes of the future. By knowing that these stem from the values and behaviors of different cohorts, leaders and communities can craft responses that are empathetic and effective – be it tailoring healthcare systems for more seniors, creating family policies that encourage people to have children without sacrificing careers, or educational exchanges that prepare youth to thrive in a globalized world. In writing this essay as a kind of thoughtful magazine-style journey, the goal was to illuminate the grand sweep of forces and the human-scale responses of generations. The grandmother and granddaughter in Nairobi may not use the same slang or gadgets, but they share the same society, one shaped by waves of change that lifted each in different ways. The granddaughter’s world of instant connectivity and conscious choices is a product of decades of technological and cultural currents; the grandmother’s wisdom about community and resilience was forged in a time of different trials and triumphs. Both perspectives are valuable for navigating what comes next. As we sail into the future, the winds of technology, economics, politics, and globalization will surely blow new storms and fair weather our way. But by understanding generational cohorts – these crew members on humanity’s ship, each with their own experiences – we gain not only clarity about how change affects us, but also a sense of continuity. The voyage is ongoing, and each generation both inherits the world and transforms it, steering our collective trajectory in ways large and small. Appreciating this interplay across time makes us better equipped to face the challenges and opportunities of the coming decades together, as one global society made up of many generations.

Sources

- Gu, D., Andreev, K., & Dupre, M. (2021). Major Trends in Population Growth Around the World. China CDC Weekly, 3(28), 604–613. [United Nations Population Division data on global fertility decline and population aging】 .

- Dattani, S., & Rodés-Guirao, L. (2025). The baby boom in seven charts. Our World in Data. [Analysis of the mid-20th-century baby boom’s causes and patterns, e.g., rising birth and marriage rates in the 1940s-60s】 .

- EY Global. (2025). The first global generation: Adulthood reimagined for a changing world. [Global study of 18–34-year-olds in 10 countries, highlighting shifts in life milestones and values (e.g., rethinking the traditional life script)】 .

- Pew Research Center / Tyson et al. (2021). Gen Z, Millennials Stand Out for Climate Change Activism. Pew Research / Nature. [Findings that U.S. Gen Z is especially concerned about climate change (76% calling it a big concern)】 .

- Pew Research Center / Fry, R. (2020). Millennials overtake Baby Boomers as America’s largest generation. Pew Research Center (Fact Tank). [Report based on U.S. Census data showing Millennials surpass Boomers in population size】 .

- Our World in Data. (2023). Age Structure. [Global demographic data showing turning points such as more over-64 seniors than under-5 children as of 2018, and comparisons of age distributions (e.g., Japan vs. Nigeria)】 .

- United Nations. (2020). International Migration 2020 Highlights. UN DESA. [Statistic that international migrants reached 281 million in 2020, up from 108 million in 2000, reflecting globalization’s impact on migration】 .

- Benchworks. (2025). Navigating the New Wave: Tailoring Pharma Marketing for Millennial Doctors. [Industry article citing Pew Research data; notes Millennials’ digital nativity and the fact that 94% of young adults use social media daily and that Millennials have become the largest adult generation in the U.S.】 .